(This is part I of a three-part report.)

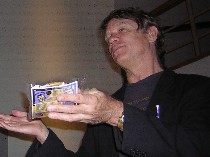

Artist Allan McCollum attracted quite the crowd at his lunch-time talk yesterday at the University of the Arts. He was the third artist to speak in this summer’s UArts Brown Bag Lunch Series,”Food for Thought.” Over the years, the program has brought in memorable artists like Jose Bedia, Dario Robleto and Siah Armajani. The series is organized by Carole Moore who heads up the Summer MFA program there and most important of all includes air conditioning. The rest of the schedule for these talks is here (right, McCollum from a very strange angle, sorree, but I love the hands).

I arrived in a serious sweat, having decided (oh, what possessed me?) to bicycle down there in the appalling humidity, and radiated heat for the first hour of the talk. People kept asking me about my tan. I was probably just beet red from exertion and the high humidity. I can’t imagine why Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery Director Sid Sachs or anyone else for that matter would have sat next to me in that state.

But Sachs did share with me that McCollum’s website is amazing, so here’s the link, where you can see decent versions these same photos that I have posted here. (I personally am amused that the images here are copies of McCollum’s art of making copies). Sachs also mentioned that McCollum was generous and sensitive, unlike so many self-absorbed artists, and certainly the talk bore that out.

Anecdotes

But best of all, Sachs offered a couple of funny art anecdotes.

But best of all, Sachs offered a couple of funny art anecdotes.

Here’s my favorite one: Sachs was wandering through Strawbridge’s when he espied some giant ginger jars in solid colors–basically copies of McCollum’s “Perfect Vehicles,” giagiant ginger jars, in this case turned to use as store decor. Now McCollum, who is a man who makes copies of copies, questions uniqueness and uniformity, and thinks mass production is a good thing, would really have loved these copies. So Sid tried to take a photograph, but store security intercepted him before he could focus. What would have been the pinkerton scrooge’s point, I wonder? He was protecting copies of copies from being copied. Then again, maybe that proves McCollum’s point about the value of the mass produced item (left, one of McCollum’s extra-large “Perfect Vehicles”).

McCollum himself told an anecdote about being asked to supply props for the movie “American Psycho.” However the filmmakers didn’t want the responsibility of keeping the artwork safe, so McCollum gave them permission to copy his work and then they sent him the copies when they were done. He now has them, six “Surrogate Paintings,” or maybe he meant six surrogate paintings.

McCollum brought more slides than I’ve ever seen in a slide talk, many of them duplicating the same art work in different venues–a sort of mass-produced slide show–but he kept everyone’s attention nonetheless.

Moore did the introduction, stating that McCollum, who was born in Los Angeles and lives and works in New York, explores in his art how objects change personal and public meaning in the world. McCollum has had more than 100 solo exhibitons in galleries and museums around the world and is in the collections of 70 major art museums around the world (I didn’t know there were 70 major ones). He has also written about other artists, among them Matthew Mullican and Andrea Zittel. (Speaking of Mullican, see Roberta’s post on a collaboration he and Mullican produced that we saw in New York).

McCollum started by saying he hadn’t gone to art school (I heard an intake of breath all around the room, I do believe).

The early assembly line

Fairly early on in McCollum’s career he moved to making a larger image from small strips of canvas and then from uniform squares of canvas–the beginnings of the relationship between McCollum’s art and mass production, a theme that has persisted in his work ever since. He said the process of assembling all the squares into a piece was a Fluxus-like event, adopting mass production techniques. “I didn’t know what it would look like until I did it,” he said (right, detail from a work in the “Constructed Painting” series).

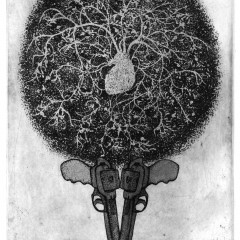

Then he showed “a kind of kit” he designed, created in multiples using the paper lithograph method of printing that had swept into print shops (like PIP) across the country. He said the method was an influence on the anti-war movement, enabling cheap reproductions of pamphlets before xerox came along. It also was a kind of mass production technique that appealed to him. He took the kit’s shapes and glued them together to get grids on grids (left, a kit of shapes).

“There’s some humor in this,” he said. At the time at Art Forum, there was a lot of writing about the edges of the canvas being the first four lines of your composition. “So I’m making a painting with nothing but edges.”

He also mentioned as an influence here Richard Tuttle and the idea of making something that you might throw away.

When he moved to New York in the mid 1970s he began questioning the critical assumptions in his work. He came from a poor family that valued mass produced objects, so he himself valued them.

He said he wanted to make a painting that stood for all paintings. “If I was an anthropoligist from Mars trying to describe a painting, what would I say to my people?” (right, a “Surrogate Painting”).

He began to wonder about the expectation that people bring when walking into a gallery, the social space in which an art work flourishes. He wanted to figure out “that longing that precedes looking at an artwork…what precedes your walking in the door” of a gallery.

Then he began looking at paintings on television. They are ever present in the background of dramas and sitcoms where everything but the frame is blurry and indistinguishable–but the viewer accepts the thing in the frame as a work of art with all the values having such a thing represents. Why, they could be mass produced and still have the same effect (left, a tv still with unreadable paintings in background behind JFK).

He began by making monochrome paintings. “But I didn’t think I was making monocrhome paintings.” However, the work was chosen for shows of monochrome art, like the show “Dark Paintings, Dark Thoughts” [sic.] Sachs leaned over to tell me he too was in that show, which was really called “Black Paintings, Dark Thoughts.” I refuse to do a search to double check on this. This way either one can be right in my mind (left, “Plaster Surrogates,” cast plaster one-piece objects painted with enamel).

McCollum’s monochrome art objects included the “painting” and the frame, but really the whole thing was the painting.

They sold (here’s a group of them bought and installed by someone at Chase Bank).

This discovery that art isn’t necessarily about the quality of the image inside the frame inspired him to begin making enormous blow-ups of photos he took off the television screen of the indecipherable television art–“You see four or five every night.” He hung the “Perpetual Photos” in galleries, where they looked great, all framed and layed out across the white walls (left, a blown up piece of television art).

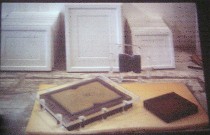

From there he mass produced plaster molds of paintings, including the frame and the mat. But, he said, each one was unique. “Anyone that’s ever made cookies knows that.” He made them in 20 sizes and used 32 colors. But he made no two combinations alike (left, a grouping of “Surrogate Paintings”).

He was working cleaning buildings around that time, allowing him to look across the street into windows of other buildings. Again he saw artwork he couldn’t decipher, and so photographed, blew up and duplicated those as well. He also used newspapers as a source for indecipherable art. He said art was “about the desire to see a picture.”

(This is part 1 of a three-part report; part 2 is here and part 3 is here. These talks, by the way, are recorded and archived in the UArts Summer MFA office and in the UArts library.)