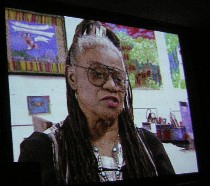

When Faith Ringgold grabbed my hand and focused on my face and said “A blogger, a real blogger” (or maybe it was …a real life blogger), I had no idea that she might be the funniest woman alive (Ringgold in a video image).

Unfortunately, what makes her funny is the way the delivery undercuts the words. So this is the last bit of humor in this post.

Ringgold was in town earlier this month because Moore College was honoring her with its 2005 Moore College Visionary Woman Award, which also went to Wilhelmina Cole Holladay, the founder of the National Museum of Women in the Arts (NMWA). They were being honored for challenging inequities in the art world, which had previously been an white-male, Eurocentric domain (oh, well, it still is, but at least women and non-Europeans have some presence now). The two were at Moore earlier this month to participate in a panel discussion (can only two panelists equal a panel?) aka the Elizabeth Greenfield Zeidman Lecture.

Ringgold (I can’t believe you don’t know this but I’m going to tell you anyway) is an artist who makes story quilts, books, paintings and other art forms with influences from her African American, American, and African heritages. Her art, and her struggle to bring people of color and women to the Eurocentric art world, have earned her both fame and admiration–and of course this most recent award. There have been lots of other awards (her resume states more than 80), including her first honorary degree, which also came from Moore, back in 1986–so many awards she is practically a national institution.

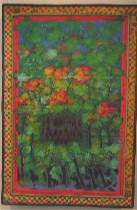

Don’t let her widespread acceptance deter you from seeing her show or make you assume her work is bland. And don’t let the fact that you’ve seen one of her “Tar Beach” story quilts over at PAFA a few too many times deter you either. The work is fresh, beautiful and rings as true as ever (image, Ringgold’s “Coming to Jones Road #6: Baby Freedom Came One Night,” acrylic, canvas and canvas painted border).

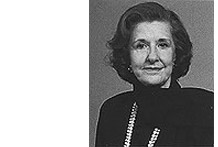

So for the talk there was Ringgold, with elaborate swags of plaited hair and swags of printed African-looking fabric. And next to her sat Holladay, coiffed in a proper pageboy topping an outfit of a dark jacket and slacks.

Although Holladay lacked Ringgold’s ebulliance and exoticism, she was no slouch–fierce in her righteous anger about the virtual absence of women in art historical literature and about the need for the museum she founded in 1987. NMWA began with her and her husband’s personal collection of 500 works of art by women. Its collection has since grown to more than 3,000 works of art. She too received an honorary degree from Moore, back in 1988 (image, Holladay).

Holladay began her journey to founding the museum when she and her husband acquired a piece of art they saw in Europe by an unfamiliar woman artist, Clara Peeters. When Holladay began to research this 17th century Flemish painter, she could find no reference to Peters in her art history literature. That was when she came to realize that Jansen, the bible of art history 101, was a male preserve. “There was not one woman in any of our books,” she said. The experience, she said, turned her into a feminist (image, Peeters’ “Still Life of Fish and Cat,” from the NMWA website).

Ringgold, who began her art career in the midst of the Civil Rights and the Black Power movements, had trouble breaking in. She finally got into the Spectrum Gallery, but “people didn’t want the work.”

She explained her own eventual success like this: “If you stay in game, your going to wear everybody out. They’re going to say, Oh God, let her through.” (If you watched Scorsese’s Bob Dylan movie last night, you might reach a similar conclusion: Persistence is one of the basic requirements of success, even for a genius.)

What inspired her, Ringgold said, was people and how they handle the situations they find themselves in. She’s a teller of stories in much of her art work using words and visuals together. (I have a soft spot for art like this that’s not hermetically sealed in some theoretical, inaccessible framework.)

How Ringgold came to quilts was that in the ’70s she started making 3-D objects and tangkhas. But the tangkhas were of limited size, whereas a quilt “you can make the size of this room,” Ringgold said. She also liked quilts because, they “came here as an art form from Africa.”

Discussion moderator Tracey Matisak, from WHYY-TV, asked Holladay why there was a lack of art by women. Holladay suggested that because women led protected lives, they were left out of popular (male-written) writings about art. She didn’t think it was deliberate, saying the earliest woman writing about art was in the 1890s. Nonetheless, she was shocked by their absence.

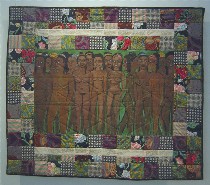

Ringgold, however, said that the exclusion was deliberate, part of an elimination process. In the art world, “you have to eliminate as much of the competition as possible.” Two groups you can identify and therefore exclude easily are blacks and women (image, “Faith Ringgold’s Over 100 Pound Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt.” That’s Ringold at her many weights and sizes over the years).

“It’s a very powerful thing to create ideas and shape cultures,” she said. “That’s what artists do, shape culture.” Men realize they need to keep that power to themselves–the art world version of the victors getting to determine what the culture is and to document it.

Holladay disagreed. “Peple like what they know. While I don’t think any museum director said, we’re not going to show women, for 130 years the Metropolitan Museum of Art [didn’t have a show of any woman artist]” (detail from M.L. Van Nice’s installation at the NMWA, “The Library at Wadi Ben Dagh,” to Nov. 6).

Even now, most people can’t name five women artists; they start with Grandma Moses, then mention Mary Cassatt and George O’Keefe. “And then they start hemming and hawing,” Holladay said.

She defended NMWA against the criticism that women should be in museums with men. “Well, of course, but they weren’t.”

Ringgold spoke little about her life as a black, female artist, evading questions about the specifics of the problems she had faced. She switched to the bright side: “You must almost feel like the Lord must feel, because you are a creator. …It’s like a birth… and it’s coming from your energy, but you don’t know how you did it and you don’t know what it is. You won’t know until others see it.”

Matisak asked Holladay about outsider art and women’s creations. Holladay started to talk about Belgian lace and Japanese appliques as art, thereby irritating Ringgold. “What you did, you changed the subject,” Ringgold said to Holladay. “The subject is really folk art. Folk art, it’s very different from painting. They cost different amounts of money.” I wasn’t sure how to take this, but I thought it was pretty funny.

Ringgold found another bright side to being excluded. “When you don’t give a person anything and you don’t show them the value of what they are doing… I was free to do whatever I wanted to do. I wasn’t being promised anything. Others were trying to please, but they were being ignored, just like me. At least they were going to know I was there. They’re angry. They didn’t do what they could have done at the time they should have done it. I did seize the time.

“It could have not worked for me. I had some luck, and a lot of people to help me along the way. I feel extremely lucky for my life today.”