I had coffee yesterday morning with Lisa Kereszi at the Green Line Cafe. We sat outside in the sun with our coffees and somehow I managed to take some notes in spite of the drink (usually can’t drink something and take notes at the same time).

I had coffee yesterday morning with Lisa Kereszi at the Green Line Cafe. We sat outside in the sun with our coffees and somehow I managed to take some notes in spite of the drink (usually can’t drink something and take notes at the same time).

Kereszi (pronouced kerezzi) is the photographer who has a show of her work on exhibit at Moore College right now, in the gallery space next to the one now occupied byFaith Ringgold’s work. Both shows are worth a visit and I’ll get back to the shows, and some more about the fabulous Ringgold, too, in another post.

Kereszi won the prestigious 2005 Baum Award in Photography and she worked for photographer Nan Goldin (there’s a nice piece at artnet.com by Mia Fineman on Goldin here); Kereszi is a Yale M.F.A. alum, undergrad degree from Bard, and she’s now a lecturer in photography at Yale. You can see a lot of her work here. Among her collectors is the West Collection (I put that up for its local connection).

As for the Green Line, I like the place and wanted to give it a plug. In an email after our chat, Kereszi said the neighborhood reminded her of Park Slope.

Which is not to say she’s exactly an out-of-towner, although she now lives in East Williamsburg. Kereszi was born in Chester and grew up nearby in Delaware County, the daughter of a biker (“He looked rough, still does”) who ran the family junk yard.

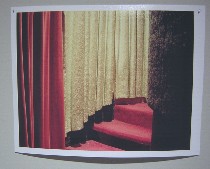

And that explains the title of the exhibit, “Lisa Kereszi: A Previous Life.” Somewhere along the line she explained that what she wanted to do was escape her past. But the photos go back to it. There’s an amazing photo of her father’s rug, a U.S.A. eagle with bits of dirt and dropped coins of a life out of control. There are the tawdry drapes dressing up the walls of rooms (top), the seedy wall below peeking out from underneath the even seedier drape–a flash of stocking peeking out from under the skirt (image, “Bicentennial rug, Dad’s Room, Media, PA).

“I grew up living an outsider lifestyle and I didn’t want to be that. I wanted to do well in school, be successful and ambitious,” she said. “I didn’t necessarily want to be rich or have a nice car or that kind of stuff.”

Kereszi took pictures at the junk yard, which her grandparents owned when she was a teenager at Penncrest High School. Her mother ran an antiques shop. So it’s no surprise that the junk-yard aesthetic, with its concept of collecting and recycling, still impels her work. “I love the idea of rescuing something from oblivion, from not existing anymore. …but not just any old thing.” What she’s collecting are things that are metaphors for something else (the Cadillac, with its triple dose of longing for living on the town–the car, the skyline, the detailing–is in the “Joe’s Junkyard” series).

The surprise is in the opposing impulses in the work–to escape and yet recapture her past.

Not that she analyzes her choices while she’s working. The choices are intuitive, she said. “I’m looking for the one little detail that means something to me. I’m interested in the very recent past.”

Some of the places she photographs are not abandoned, but she said, “Its important to me that there are no people in it.” But what interests her are the traces of people in the places she explores.

I pointed out she had so photographs of burlesque dancers that didn’t fit those perameters. “My friend is a friend of a burlesque dancer,” she said. It’s not the only contradiction. There’s also the Florida mermaid (image). Then she talked a little about the conflict between doing commercial work and doing her art–she was worried that the commercial work would make her “too soft” and she wanted to stay “hard” for the art work.

Her commercial track record is pretty impressive, including The New York Times Magazine and The New Yorker, Details and Penthouse. The list goes on. “It pays the rent.”

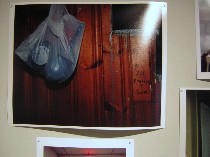

Kereszi wants to make sure that she’s not doing what other photographers of what’s seedy are doing (but she doesn’t want to name them, not wanting to appear to be saying something negative about their work). I name Zoe Strauss, whose work has no sense of avoidance or escape of anything, but a rapacious curiosity, and a passion for content and concept. Kereszi doesn’t know Strauss’ work. Kereszi is as much about the creation of something beautiful out of what’s seedy. I don’t think that’s Strauss’ agenda. Yet there are times when these two seem to cross over into one another’s agendas (image, Kereszi’s grandfather’s basement; his inscription on the wall reads, “All humanity is scum”).

Later, Kereszi emailed me with these thoughts:

I try to be careful when photographing things and people who are ‘over-the-top.’ Something that I do consciously think about is how to photograph such things in a way unlike how anyone else would – in a way that says something other than just – hey, look at this weird thing.

Also, being at the Phila. Museum of Art reminded me of my affection/affinity for Surrealism and also Duchamp’s idea of the Readymade. Both of these art historical things are things I consciously realized after I had been making the pictures, not before.”

Back at the Green Line, she said, “I realized you can apply the character of a person to a place.”

Goldin’s name comes up, and she says Goldin isn’t doing the seedy thing anymore–because her lifestyle is not so seedy anymore.

Her time working for Goldin, when she was a junior in college, was an important experience for Kereszi. She interned there in exchange for one of Goldin’s prints. She got a lot more out of it, including for a while a relationship she characterized as co-dependent and difficult to end. “Nan led into Yale,” she said, by brokering a connection there for her. “I owe her a lot.”

Kereszi’s photographs are analog C-prints, for the most part, taken either with a medium- or a large-format camera. Her father’s rug and the Governor’s Island shovel in the bucket, for example, are large format. When she’s working large format, she said she has to previsualize the image, whereas for the medium formats, she shoots more and then selects.

I asked why she was working with film. “I like the way film looks. Digital things look super-real. Film has more depth. It’s light reacting with silver and dyes. It’s something tangible. Whereas digital doesn’t really exist. It’s pixels, just information.”

Not that she’s opposed to digital. She mentioned the $10,000 cost of a really great digital camera as one factor. And she does make work prints using inkjets–there are small ones in the show (like the curtains and grandfather’s basement shot).

Large C-prints, she said, are getting harder to get as labs stop making them. Joel Sternfeld’s lab is an exception. Other labs, she said, are doing digital enlargements, “layed down in lines.” She herself does digital enlargements sometimes if she gets a hair or a big piece of dust on an image that therefore requires some repair.

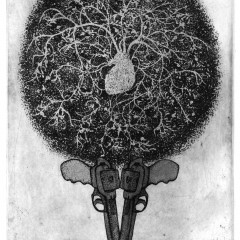

The conversation wound around to Kereszi talking about going to Bike Week in Florida, and looking at the goings on both as an insider and an outsider there. I mentioned the Bike Week photos of Burk Uzzle, and said I’d be curious to see how different her were, both for its woman’s eye and its insider-sympathy. “I remember going to Bike Week as a kid,” she said (she herself has no tattoos because “my dad’s covered with them.”) then she began to think about here insider-outsider relationship with the junkyards (image, Uzzle’s “Industrial Accident Victim, Dayton Beach, Fla.”).

Maybe she’s not saying, “Hey look at this weird thing.” Maybe what she’s saying is look at this weird thing that’s a part of me–and not.

“Escape. That’s the word.”