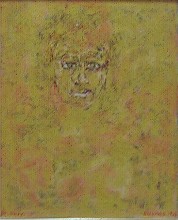

A personal who’s who of bohemia and the arts in the mid 20th century is one of the highlights of “Beauford Delaney: From New York to Paris,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Which is not to say the art isn’t great (image, “Self-Portrait, Yaddo”).

A personal who’s who of bohemia and the arts in the mid 20th century is one of the highlights of “Beauford Delaney: From New York to Paris,” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Which is not to say the art isn’t great (image, “Self-Portrait, Yaddo”).Here’s why you need to go for the art. I have put side by side on my computer desktop my picture thumbnails of Delaney and a more typical set of picture thumbnails. I couldn’t keep my eyes off Delaney’s sparkling colors and jazzy rhythms. Unfortunately, at this scale, the busy-ness of the Delaney’s don’t translate so well. (right, below, a comparison between Delaney thumbnails and others on my computer desktop).

But quality aside, the press opening was an unusually intimate affair, with just 20 or so in attendance. Usually, there’s a company line when the PMA puts on a press preview, an effort to make sure everyone is on message. But this time, Delaney’s first name got pronounced bowe-ford and byou-ford, with a concession by all involved that the artist accepted both pronunciations.

But quality aside, the press opening was an unusually intimate affair, with just 20 or so in attendance. Usually, there’s a company line when the PMA puts on a press preview, an effort to make sure everyone is on message. But this time, Delaney’s first name got pronounced bowe-ford and byou-ford, with a concession by all involved that the artist accepted both pronunciations.

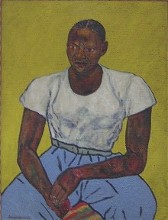

The show curated by Sue Canterbury for the Minneapolis Institute of Art includes some local additions, the most outstanding being his 1945 portrait of his friend James Baldwin, the novelist and civil rights activist. Baldwin, 23 years Delaney’s junior, is the subject of a number of portraits in the exhibit, but the PMAs is a knockout, acquired in 1998. Showing him that a black man could be an artist, Delaney was a mentor to Baldwin, PMA Curator of Modern Art Michael Taylor said. Although you may well have seen the PMA’s Baldwin portrait hanging in that hallway near the art rentals, seeing it in this context is spectacular (left, “Portrait of James Baldwin”).

The show curated by Sue Canterbury for the Minneapolis Institute of Art includes some local additions, the most outstanding being his 1945 portrait of his friend James Baldwin, the novelist and civil rights activist. Baldwin, 23 years Delaney’s junior, is the subject of a number of portraits in the exhibit, but the PMAs is a knockout, acquired in 1998. Showing him that a black man could be an artist, Delaney was a mentor to Baldwin, PMA Curator of Modern Art Michael Taylor said. Although you may well have seen the PMA’s Baldwin portrait hanging in that hallway near the art rentals, seeing it in this context is spectacular (left, “Portrait of James Baldwin”).

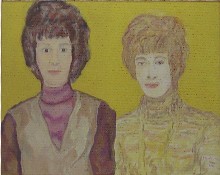

Another addition for the Philadelphia version of the show is a portrait of singer Marian Anderson. (Also on display is a fan letter Delaney wrote to Anderson). And at the end of the show is an odd, cool portrait owned by the PMA of the Locks sisters, Marian and Betty, the PMA’s first Delaney acquisition.

Another addition for the Philadelphia version of the show is a portrait of singer Marian Anderson. (Also on display is a fan letter Delaney wrote to Anderson). And at the end of the show is an odd, cool portrait owned by the PMA of the Locks sisters, Marian and Betty, the PMA’s first Delaney acquisition.

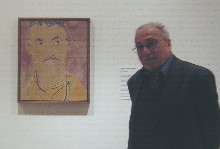

An outstanding part of the preview was the presence of journalist Richard Gibson, one of the subjects of Delaney’s portraitmaking. Gibson, then a student at Central High School and all of 14 years old (an alternate age given during the preview was 16), wrote a fan letter to Delaney after seeing Delaney’s 1947 show at the Pyramid Club. (The PMA show includes a partial recreation in one gallery of Delaney’s work from that exhibit).

The Pyramid Club was a prestigious African American club here in Philadelphia for the spiritual and social advancement of African Americans, said curatorial assistant Emily Haig (I have to check the spelling here). Artist Dox Thrash was one of the people who invited Delaney, a leading African American artist, to exhibit there for its seventh annual art exhibit. The building the Pyramid Club occupied until 1963 still stands at 15th and Girard.

The Pyramid Club was a prestigious African American club here in Philadelphia for the spiritual and social advancement of African Americans, said curatorial assistant Emily Haig (I have to check the spelling here). Artist Dox Thrash was one of the people who invited Delaney, a leading African American artist, to exhibit there for its seventh annual art exhibit. The building the Pyramid Club occupied until 1963 still stands at 15th and Girard.

Here’s the portrait of Richard Gibson (left). Gibson graciously agreed to pose next to it.

The curators asked Gibson if he would tell the story of his acquaintanceship with Delaney. Gibson said that after he wrote the fan letter, Delaney just “turned up at my house.” Gibson’s grandmother was wary and not too eager to let the artist in, but then relented. Gibson and Delaney kept up a correspondence afterward. In 1951, Gibson left for Rome and lived most of his life in Europe, except for a brief stint with CBS News.

Another portrait that came out of Delaney’s connection to Philadelphia was of Irene Rose, who encouraged his art work and hosted him here. Rose, whom he portrayed as a society patron of the arts, was really a Lefty (image right, “Portrait of Irene Rose”).

Another portrait that came out of Delaney’s connection to Philadelphia was of Irene Rose, who encouraged his art work and hosted him here. Rose, whom he portrayed as a society patron of the arts, was really a Lefty (image right, “Portrait of Irene Rose”).

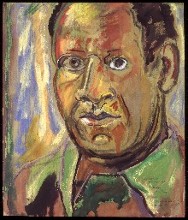

Included in the show are portraits of boxer and actor Canada Lee that channels Van Gogh and a portrait of Henry Miller, who wrote an influential essay, “The Amazing and Invariable Beauford DeLaney” (left, “Portrait of Canada Lee”).

Included in the show are portraits of boxer and actor Canada Lee that channels Van Gogh and a portrait of Henry Miller, who wrote an influential essay, “The Amazing and Invariable Beauford DeLaney” (left, “Portrait of Canada Lee”).

Delaney had been living the Bohemian life in Greenwich Village, had sat for several portraits by Georgia O’Keefe and was tied in with the whole Alfred Stieglitz posse. But in 1953, at the age of 51, he left for Europe. Gibson visited him there in 1955 and sat for the portrait. Gibson said the two of them talked while Delaney painted.

Delaney had been living the Bohemian life in Greenwich Village, had sat for several portraits by Georgia O’Keefe and was tied in with the whole Alfred Stieglitz posse. But in 1953, at the age of 51, he left for Europe. Gibson visited him there in 1955 and sat for the portrait. Gibson said the two of them talked while Delaney painted.

Taylor said that Delaney got to Paris by raffling off a painting, “Distant Horizons.” The man who won the painting, Carl L. Leeds, still owns it, and it is also on display in the exhibit. Delaney ended up staying in Paris until his death in 1979. He stayed there longer than he originally planned. Hague quotes him as saying, “‘I came to peep but there was a lot to peep at.'”

The art, which is drenched with influences from all the French Impressionists to the Ash Can school to Stuart Davis, is also full of musical references. And once Delaney gets to Paris, he goes abstract with paintings full of rhythm and pulsating color. One piece he dedicated to Charlie Parker.

The art, which is drenched with influences from all the French Impressionists to the Ash Can school to Stuart Davis, is also full of musical references. And once Delaney gets to Paris, he goes abstract with paintings full of rhythm and pulsating color. One piece he dedicated to Charlie Parker.

But he continues painting portraits–including more of James Baldwin, and an other-worldly portrait of Ella Fitzgerald.

But he continues painting portraits–including more of James Baldwin, and an other-worldly portrait of Ella Fitzgerald.

Gibson, who remembered how he himself listened while Delaney talked and painted said, “He was a very serious artist, but also a great person.”

The exhibit runs to Jan. 29. In addition to the Delaney work, there is another exhibit, “Beauford Delaney in Context,” with selections from the PMA permanent collection.