[What follows are a series of posts by students in Colette Copeland‘s art-writing class at the University of Pennsylvania about the Slought Foundation exhibit “Almost Art”]

Post by Seth Manoff:

Carlos Ginzburg’s installation of artificial flowers taken from graves

The [exhibition] title’s irony is that regardless of the materials used, a lot of the pieces have much deeper meanings than many other contemporary counterparts that are “aesthetically pleasing.” For example, Carlos Ginzburg, in one of his pieces, has an area filled with artificial flowers taken from the cemetery. While viewers might not enjoy looking at fake flowers from the grave, it doesn’t matter. Ginzburg cares more about the ideas it evokes in the viewer, especially in this case regarding the artificiality and superficiality of American consumerism. To Ginzburg, it has become so prevalent in this country that even when people die, Americans participate in the consumerist culture of cheap, crappy artificial goods instead of higher quality more expensive goods.

Another one of Ginzburg’s works is a commentary on the famous Baudelaire quote “What is Art? Prostitution.” Ginzburg has a naked woman sitting on a chair holding a sign with the Baudelaire quote. At first sight, viewers might think that Ginzurg is making a comment about how artists prostitute themselves to the buyers (making them what they want). But, if so, why would a naked woman be holding the sign? It goes deeper than this. It could be referring to women’s role in art and society. But the most interesting thing about this work is that this is the second time Ginzburg has done this piece (he did it once in the ’70s). This leads me to ask many questions, such as: why again?, why now?, and how have things changed since the first time he did the piece? Thus, regardless of the appearance, “Almost Art” is much more than art to me.

Post by Agnes Stachnik:

One of Tom Fruin’s drug-bag quilts

It is in the spirit of Duchamp that the Slought Gallery curated its most recent exhibition entitled Almost Art. Most of the work featured in Almost Art uses unusual or unconventional materials, ranging from t-shirts and televisions to traffic cones and memorial flowers.

Like Duchamp’s productions, these works hold other meanings and hidden connotations. Artist Tom Fruin, for example, creates collages using objects he has found near housing developments. In one of his collages Fruin has diligently sewn together the plastic bags formerly used to hold drugs. The pictures on the bags, which range from leaves of marijuana to small skull heads, form an eclectic pattern against the plain white wall on which they hang. Viewers are either drawn to Fruin’s work because of its unusual nature or repulsed by its use of unpleasant materials.

Fruin did not intend for his work to be viewed solely on an aesthetic level. His collage is also a social commentary on drugs in today’s society. Drug use has become much more prevalent over the last few years, as evidenced by the numerous drug bags Fruin was able to collect. By displaying these plastic bags, Fruin reminds viewers of this problem and encourages them to take action.

Drug bags are certainly not a typical material used in artworks, and so many might not perceive Fruin’s collage as a praiseworthy piece. In this sense, Fruin’s work is almost art. By utilizing unusual materials as well as taking on various meanings, the works featured at the Slought Gallery are just on the edge of traditional definition of art.

Post by Priyal Bhartia:

Shahram Entekhabi’s video of a girl endlessly consuming a McChicken Sandwich

Drug packets, a branch of a tree, patchwork quilting, and a young girl eating a happy meal are not the first things that come to your mind when you think of contemporary art. Curator Osvaldo Romberg is not interested in the aesthetic appeal of these pieces, but more how they mirror the prevailing social conditions in our culture. The artwork is attempts to address issues like utopia, sociology and anthropology.

Artist Shahram Entekhabi’s video installation captures a young, chador-clad girl devouring a happy meal. The meal goes beyond the confines of the golden arches and addresses the issues of consumerism and artificiality. The artwork is a link between the Western consumer culture and the Eastern spiritual culture.

Duchamp’s fountain, a urinal hung on a wall, was unacceptable in 1917 but it pioneered the way for other contemporary artists. Much art today does not depend on aesthetics alone, but the creative and intellectual thought behind it. Some may consider it art and some Almost Art.

Post by Akriti Saxena:

installation at Slought of Hamdi Attia’s deconstructed television set

The juxtaposition of construction and deconstruction is an important theme of the exhibit, and is mirrored in individual pieces as well. Tom Fruin’s drug packets demonstrate this idea. Each drug packet is capable of destroying an individual (an act of deconstruction). However, drugs have become a social phenomenon. The repetitive pattern on the packets illustrates unity and how this trend ties communities together (a construction of relationships).

Hamdi Attia’s deconstruction of a television set also comments on this juxtaposition. A television, a strong form of communication, unites different parts of the world. When deconstructed, the radiation and electric fields from individual components can prove to be fatal. Clearly, the artists have little interest in showing off their artistic technical skills since aesthetics can often be distracting. The assembly of simple, everyday objects into a social commentary prods the viewer to consider the assembly of the artists’ ideas and create meaning out of the work.

Post by Kate Chovanetz:

Karen Shaw’s unraveled sports jersey draped around a column like a dress

Artist Karen Shaw, transforms male jerseys into dresses, making a satirical statement on masculinity. These ideas transcend the visual value of the works, and instead stimulate thinking. I, for one, left with the perpetual question “What is art?” on my mind, but because the works have meaning and purpose, the appreciation for this “Almost Art” might be enough to stretch people’s definitions to include the pieces at this exhibit.

Post by Katy Rose Glickman:

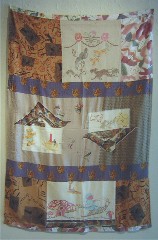

Hand-done cross stitching and piecing meets commercially printed fabric in this piece by Gian Carlo Pagliasso, raising issues about hand-made and idiosyncratic versus commercial, uninspired goods

This exhibition is very relevant because the meaning and purpose of contemporary art is constantly changing. Some of the pieces shown are seemingly simple and superficial, which is what forces the viewer to ask meaningful questions and truly interpret the work on their own. Some of the work is so simple and poorly constructed that it can be confusing to the viewer in its context (that of being in an “art exhibition”). Some of the work is actually pretty pathetic. Some of it is even boring. But that’s the theme at large, is it still art? Not much about this exhibition is “easy to understand,” which is what makes it all the more interesting.