On Jan. 13, I met with PAFA Associate Curator Robert Cozzolino(pictured above in front of Ramon Shiva’s “Chicago MCMXXIV” 1924) who gave me a preview of his then-upcoming exhibition “Art in Chicago” (see post).

The show opens to the public on Feb. 4. (See many pictures from the show in my flickr set).

In distilling the show down to a 700-word piece (which was then cut to 500 words by the PW editorial team) I find that I mis-represented Cozzolino’s intent for the show. Here’s his clarification.

Post from Robert Cozzolino

Dear Roberta:

I feel like I am something between a cranky old guy and an expert picker of nits in writing to take issue with what is good press (!) but I have to correct some things in your Weekly preview of Art in Chicago. The subject is simply too close to my heart to let it go and too splashy new in Philly to let it ride without feedback.

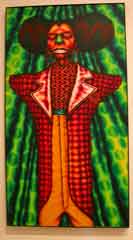

Ed Paschke, “Red Sweeney” 1975

First of all, I think you know that I admire how dedicated and passionate you are about covering what happens in Philadelphia’s museums, galleries, studios and beyond. Having written for Madison, Wisconsin’s weekly, Isthmus , I know that you only have so much space every week, indeed every month, to cover what you feel deserves to be covered. It can be frustrating to know that there are three great shows and two fascinating interviews that you want to write about but are forced to choose only one, leaving the others to simply be listed, the interviews for your own experience. Therefore, that you spent as much time and space as you have on Academy’s new exhibition is beyond wonderful. I also find it inspirational that you go beyond your regular writing gigs and cover Philly so thoroughly and with intelligence and wit. I’ve only been here for two years and have worked as a curator in town for slightly more than one. In many cases I have learned about great local artists from you first. So I have come to see Artblog as my spyscreen on Philly’s best, weirdest, and most worthy art.

Seven Lively Arts, 1947 (det) 7 panels commissioned for Ricardo’s restaurant, now gone. Right panel is “Drama” by Ivan Albright.

So please see these corrections as helpful — not as my wrath. I really do not have a wrath. Sometimes I wish I had a personal wraith. Perhaps it will touch off debate, perhaps not.

I have a couple of big concerns and a few little ones (which I am not going to touch on). The main one — and to me the most important — is that you somehow misunderstood the way in which I am framing Chicago art. I do not want to be misunderstood by you or your readers. That is

a bad thing indeed.

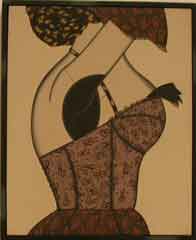

Christina Ramberg, “Shadow Panel” 1972

All of my research, curating and writing about twentieth-century art strives towards obliterating invented and pointless labels and categories. Often these labels were invented out of convenience and stuck (example: “abstract expressionism”). In many cases these catagories establish artificial norms upon which to justify old value judgements. An example: Greenbergian modernism, which dominated postwar assumptions about was Modernist (flatness, attention to paint and surface which should act like paint and surface) and therefore what was not (illusionism, narrative content).

The very very very last thing I want to do is to even hint that art done in Chicago of any period should be seen as its own category. That is exactly how it has been treated in the past as a way to exclude it from the supposed mainstream — which was often a select and finite group of artists (often favored by a loquacious and highly visible critic, very often in one particular small provincial place in the United States — any guess where?).

Ray Yoshida, “Jizz and Jazz” 1971

Categorizing art made in Chicago as its own thing in effect negatively isolates it and makes it an

anomaly. The artists in this show were actively engaged with the national — and in some cases — international art world. While there is a great deal of continuity (previously denied) among the three generations who are the focus of the exhibition, the qualities are subtle and in no way constitute a sustained movement of some sort.

Macena Barton “Salome”1936

What this show argues is that we need to expand our narrow view of what constituted modernism in America and look beyond New York. We could be looking at Dallas or San Francisco or Toronto. I believe that questioning what we have been told over and over again was the only (or correct) form of modernism in the visual arts helps us understand all of modernism much better — including the usual suspects. I am arguing for expansiveness, inclusiveness, and a more complex and exciting way of understanding the twentieth century. I do not want Chicago to be

seen as isolated from the rest of what was going on in the world. It was part of modernism, not apart from it and contributed its own aesthetic viewpoint and concerns of content to our national identity. Let’s remember that while Chicago artists and critics have lamented that artists who spent their formative years in the city eventually “fled” to New York or Los Angeles, what they took with was a piece of Chicago (think of Claes Oldenburg for instance). Why don’t we talk about that process being positive and recognize a powerful Chicago diaspora?

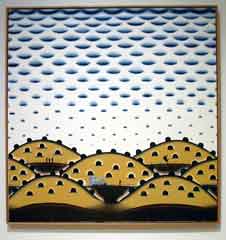

Roger Brown, “Buttermilk Sky” 1974

Second — while surrealism was a strong influence in the city over a long period of time there were many other stimulants; these artists were not “surrealists” — but took cues from the movement’s major artistic and literary figures in order to achieve their personal aims. One consistent theme in this exhibition is that each generation insisted — in a nutshell — that they

were doing their own thing. They knew about Duchamp and Kandinsky, and Dali, and Miro, Dubuffet, Bacon, Warhol, etc. But they tried to make something personal and unique in the face of these examples. That is one reason why the later generation (including members of the Hairy

Who) responded so strongly to anonymous folk art and the art of self- taught artists like Yoakum.

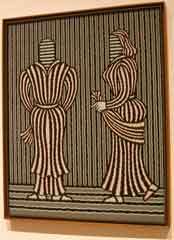

Paul La Mantia “The Fragile Trust” 1971

As for Yoakum; it isn’t true that members of the Hairy Who “discovered” him. It was more complicated than that. According to one version of the story, a couple of people saw Yoakum’s work (John Hopgood and Tom Brand) and then introduced it to a dealer in Chicago named Edward Sherbeyn. Sherbeyn gave him a show in 1968 and Karl Wirsum (Hairy Who artist) saw the work there. He introduced the others, including non-Hairy Who friends Roger Brown, Barbara Rossi, Ray Yoshida to the work. It is more accurate to say that they championed him like no one else. They treated him with great respect and helped him attain greater recognition, something that continued after his death. By extension I think they helped draw more attention to America’s self-taught artists and raise cultural consciousness about them.

I’d hate to think I wasn’t clear on these things and am sorry if I was muddled in my explanations during your visit. It was a friday the 13th after all.

In writing all of this I cannot help think of Dali’s famous aphorism, paraphrased here: “It is not necessary that people speak well of Dali, only that people speak of Dali.”

It is hard for me to feel comfortable complaining about good press; but I feel at least you should know of these corrections.

Hopefully this all makes sense.

Cheers,

— Bob