John Murphy’s two still lifes from the series That Way the Feeling Never Ends

Visions of paradise in today’s art world have less to do with religion and more to do with safety from an unmanageable world gone awry.

To judge by a couple of interesting shows now up, paradise is in a little box and it’s an imitation of nature and reality.

One of the exhibits is a three-artist show at Peng Gallery. Here, in the photographic works of Charmaine Caire, John Murphy and Shannon Slattery wear their artificiality like a badge, with candy colors and nostalgia for some past perfection that never existed.

detail of the “Bioluminescent Firefly Experiment” installation by Scot McMahon and Ahmed Salvador

The other is a collaboration by two artists at the University City Arts League photographers and longtime collaborators Scott McMahon and Ahmed Salvador. At the Arts League, “nature” is a positive transparency displayed on a light box.

In McMahon and Salvador’s “Bioluminescent Firefly Experiment,” photographers McMahon and Salvador exposed the light-sensitive film to the light of fireflies in a container. Also within the contain are some objects illuminated by the firefly light.

image from McMahon and Salvador’s Bioluminescent Firefly Experiment

The resulting images suggest nature and the universe, the fireflies themselves at times suggesting Tinkerbells bobbing around some landscape or skyscape, comets and stars.

PETA alert: The artists say they released all the fireflies back into nature, except for the one that went MIA. Perhaps he escaped; after all, his body was never recovered.

image from McMahon and Salvador’s Bioluminescent Firefly Experiment

The kick of these images is they look like nature caught at its most magical, but they were taken in thoroughly artificial, small setups, and they are displayed also in setups that smack of television screens and computer screens. (This is by far the hippest show I’ve seen at the Arts League, which is now operating under a new director, Jacquie Bowman. If this is a sign of things to come there, it’s a good sign indeed).

Loan Shark by Charmaine Caire

At the other end of the faux nature spectrum, the work of the three artists at Peng Gallery glories in its artificiality.

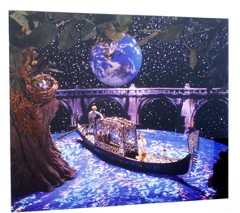

Junior Year Abroad by Caire

Charmaine Caire’s tableaus are operatic and melodramatic, with doll figures and dream-like danger in the idealized sets. The sky is only inches past the foreground, but the overwrought details and candy colors add up to a confectionary version of a remembered fear. In Junior Year Abroad, Caire shows a girl doll in a gondola with only a shirt on. It’s a fantasy that’s good and bad, scary and delightful. The photos are chromogenic prints.

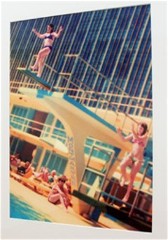

Dive by Shannon Slattery

Memories also color Shannon Slattery’s archival ink jet prints, which are souped up versions of real family snapshots. But the pinks are pinker than pink, the sea-blues bluer than blue. The family vacation at the Montmartre Hotel takes on a kitschy perfection, a dream version of a deco seaside resort.

Dad by Shannon Slattery

The people become stereotypes of a real family, looking dated and a little dorky and quite real. Pumping up the color transforms an ordinary vacation into a misleading archive of perfect memories that all snapshots aspire to reach.

two still lifes from the series I want to be Part of the Scenery, by John Murphy

John Murphy is the one who’s closest to video games in his set-ups, digital photos of set-up scenes with plastic flowers, manufactured birds and grass. There’s a reminder of saccharine greeting cards and serious Audubon prints. But the saccharine is as faux as the nature. And the cropping of the pictures invariably suggests we’re getting just a slice of an endless paradise that exists beyond the edges. The colors have the videogame intensity as well as its endless replication.

I worry that what the work of these artists means. The space it parades before us is no space at all, a sort of flatness a la Henri Rousseau. It reflects a shrinking of our horizons in the real world, boxed in by televisions, computer screens and camera lenses.

But even more importantly, I worry because the work suggests that what we think is real is really faux emotions, faux colors, faux memories and faux natural world. How can we tell if the news is really the news if the photographs before us are on such shaky ground?