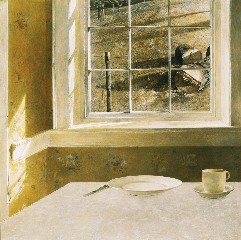

Love in the Afternoon, tempera on panel, 1992; the window, a repeating metaphor for the artist, looks out on the wide open spaces that rise up at a scary angle in a typical Wyeth approach/avoidance conflict

So many of us plan to reject Andrew Wyeth before we even get to his 70-year retrospective at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

First kiss of death: he’s popular and accessible. Second kiss of death: familiarity breeds contempt–his paintings are so familiar that they seem like cliches. Third kiss of death: We know far too much about his personal life much to his and our chagrin. Fourth kiss of death: He’s so conventional and if we never see another Chadds Ford or Maine landscape, we’ll live happily ever after. Fifth and final kiss of death: He has inspired a legion of annoying imitators like Bo Bartlett.

Public Sale, tempera on panel, 1943, depicts the sale of a family farm, the loss reflected in the landscape, the choppy patterns of the hay and tire tracks a surprise

But, as usual, every time I go kicking and screaming to a PMA exhibit, because I’m such a know-it-all, I get kicked in the butt.

So I have to say, after my tour around the paintings, that I have to forgive the guy (except I can’t really forgive him for spawning the parade of overwrought surrealists working in this region).

I’m not saying there isn’t some truth in my list of five fatal points. But there’s also some truth in the work, which transcends the conventional wisdom.

Just to backtrack a little, the artist, born in 1917 and not quite 20 when he has his first solo exhibit, at the Philadelphia Art Alliance, has another the next year in a New York gallery, MacBeth. The gallery sells out his first watercolor show! He has been living off his art ever since. He is still painting. He’s a phenom.

The work’s superficial willingness to please–its ostensible realism rooted in the world that we see–is mostly on the surface. A harsh undercurrent suffuses a lot of the work, delivering nasty surprises with formidable technique. And the real in the work is not really real at all. Like all paintings, reality has been transformed, edited and put to other purposes, some of them deeply emotional and autobiographical, some of them aesthetic, and some of them in the service of narrative.

When the those elements meet and are most successful, the paintings deliver.

A man who eats with a knife, his dinner awaiting, and a log with teeth in Wyeth’s Groundhog Day, tempera on panel, 1959; the man is Chadds Ford farmer Karl Koerner

For artists and students wondering about how painters make their choices, a gallery exhibiting the series of sketches leading up to two of the paintings is not to be missed. Groundhog Day started out as figure studies, only to become something else entirely. The figures disappear in the final product, but their presence remains in metaphorical objects and their relationships. This is a scary painting, a portrait of Chadds Ford farmer Karl Kuerner and his dog as a duo with sharp edges, of Kuerner’s subservient wife Anna, and ultimately of the artist as both naive and not so naive. The late-day sunshine shining on the domestic scene of a set table belies the message of menace.

Wind from the Sea, tempera on Masonite, 1947; it’s a crowd pleaser

So many of the paintings reflect the mixed emotions of the painter, who veils himself and his subjects in layers of masks. Looking from indoors out, the windows become his eyes, but what is outside is vast and free and unsafe. The inside is compressed, confined and maybe not as safe as it seems. He is a man haunted by deaths, such as the untimely death of his father, killed by a passing train, the deaths of his friends, his own dreamt-of death during surgery, and the annual death of the seasons.

Her Room, tempera on panel, 1963, is wife Betsy’s room, in perfect order, a nautilus as a metaphor–for her? for him? Wyeth admitted that in some sense he was wife Betsy’s prisoner according to Curator Kathleen Foster

It was too hard for this young man, home schooled and from a family of painters, to get away from narrative and representation. But he discovered how to use those conventions do deliver ultimately duplicitous paintings that at once reveal so much and so little. Ironically, the way the show is presented is rich with gossipy details of what’s and who’s behind the paintings (although it has the good taste to include only one painting only of his then-secret model Helga Testorf, and does offer a whole gallery of portraits of his wife Betsy).

All in all this is quite an interesting show.

homespun giftshop fare

I have to mention the gift-shop kitsch, which highlights things like fall-colored leaves, harvest-related objets in baskets and other touches of nostalgia for nature and farm life. Pretty funny.

And also check out the fabulous Kate Javens painting, “Named for Andrew Furuseth,” on your way out of the show, in the Dorrance Corridor, part of an exhibit, Andrew Wyeth in Context.

One more thing: There are Amtrak and hotel packages if you’re coming here from out of town, as well as concurrent Wyeth exhibitions at the Brandywine River Museum and the Delaware Art Museum.

Guest curator Ann Knutson organized the exhibit for the High Museum in Atlanta, and the PMA’s American art curator Kathleen A. Foster oversaw its installation here. They and PMA Curator of Modern Art Michael Taylor contributed to the catalog.