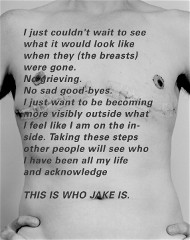

Clarissa Sligh’s photograph of Jake, back when she was Deb, from the series Jake in Transition

Although Roberta and I went to the Woodmere Museum’s second Triennial of Contemporary Photography a week ago, I am still pondering some of what I saw, namely the photographs and text by Clarissa Sligh.

Sligh, who teaches at the University of Pennsylvania, documented the transformation of someone born a woman who was so sure she was really a man that she underwent sex-change surgery and hormone treatments.

The photos of Jake are sometimes breathtakingly beautiful, sometimes hard to look at even from the corner of my eye, sometimes both all at once. I should explain that I’m a little squeamish. I haven’t even gone to the Body Worlds exhibit at the Franklin Institute, even though I am curious and heard it was great.

But the picture I found most disturbing bothered me for other reasons.

It was a breathtakingly beautiful picture of Jake from the rear, after he had undergone the breast reduction surgery and already was showing some male physical traits. The photo captures this transitional figure standing with his baggy jeans dropped just below the rear end, awaiting a syringe poised above the hip for injection. Jake’s creamy torso is smooth and shapely, looking for all the world like a classical sculpture of a nude woman from behind.

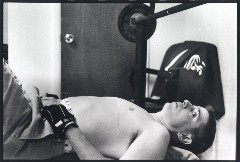

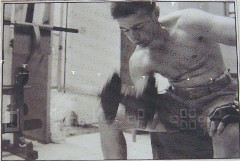

The image calls into question the other photos showing Jake working out with free weights, looking macho and tough (not to mention horribly scarred).

The photographer’s eye vs. the subject’s eye

The torso seemed to say the other photos were of Jake as he preferred others to see him, but this was the way Sligh saw him…and us too, as the viewers being given the tour of Sligh’s point of view.

The photograph was a sort of summary for me of what I thought Sligh was getting at. She stated in the accompanying text that she was disturbed by identity issues, the inside versus the outside, the expectations of others versus the interior person. And her installation broadened the sexual identity issues to race identity issues with the retelling of a story of slaves who hid their identities to escape. The story she told was of Ellen Card, a light-skinned slave who hid both her race and her gender, pretending to be the young master of a man who really was her husband, but whom she treated as her slave during their flight to freedom.

Some of Sligh’s narrative about Ellen Cope passing as a white boy to escape from slavery

Passing

Sligh said in her story that although she was familiar with instances of African-Americans passing as white–in essence, becoming white because who’s to say otherwise–she found the notion of a woman becoming a man more unsettling. After all, we are our bodies, and we are our gender, even if we identify ourselves as non-standard versions of our sex.

It’s a marvel of the human mind to adapt to who we appear to be. We adapt to our names and become those names. And we adapt to our appearance and become our appearance.

Layers of deception

But to just say these sexual traits are not only not who we are, but are a lie we cannot tolerate, and then to create a body that is basically a lie about who we are and declare it the truth, is startling and unsettling.

The overlay of society expectations may be similar for race and gender, but the underlay of biology is not really similar. Afterall, geneticists tell us there is no race. So passing for white is about this society and its hierarchies and castes. Passing for a different gender has some of the same elements, influenced by society and its definitions of male and female.

But most of us are not deeply disturbed by Some Like it Hot and Paris is Burning.

The unkind cut

When we go beyond passing, however, which is about acting and posing and undermining the rules, and go to our fundamental biology of cutting ourselves up, it’s more disturbing. Can we actually change ourselves this much? I don’t know. The pictures suggest otherwise. Afterall, the testicles Jake so painfully acquires are not real testicles. They are the semblance of testicles.

Clarissa Sligh, Untitled, from Jake in Transition, 1996–2006, gelatin silver print, 16 x 20 inches, collection of the artist.

But I wonder how different this is from French artist Forlan, who disturbs me greatly with her plastic surgery self-transformation of her face. I wonder how different this is from Chris Burden‘s gun shots in which he doesn’t really change how he presents himself to the world, but just hurts himself. Somehow, I find this less disturbing. So is the issue about how we look, if Burden is less disturbing? Also, I would say that the first time I heard about Burden, I was deeply disturbed, so there’s some inurement going on here. But nothing has inured me to the horrors of Forlan‘s plastic surgery.

I have a friend whose son used to be a woman. I find this knowledge less upsetting than looking at Sligh’s pictures, having the process go on in my face.

Faces

Even in the recent case of the woman, mauled by a dog, who acquired someone else’s face by plastic surgery, there’s still a sense of horror about identity. This was not exactly voluntary surgery. But there’s something about a face that is so personal, so much our own, with no two alike. To overcome that identity is somewhat shocking.

I recently read a pair of books–Lucy Grealey’s Autobiography of a Face and Ann Patchett’s Truth and Beauty–both about Grealey, who lost a huge percentage of her lower jaw to cancer as a child, and who spent the rest of her life dealing, not dealing, looking for restoration and over and over again facing disappointments as each new surgical attempt to give her back a jaw only ends up maiming her more. The woman who was Lucy Grealey was extraordinary in many ways, and the two books offer shockingly different views of her. Piecing together the disparities and looking for the truth of her identity was part of the interest of reading the two books that are both about Grealey’s search to restore on the outside who she was on the inside.

But ultimately, it was that damaged face who she became. So there is this incredible ability we have to incorporate what we are on the outside into our characters. And if we think we look like the other gender, we are the other gender, and if we think we are the other gender, there’s some rationale here for changing our bodies to match.

How we look is a powerful factor in how the world responds. In Calvin Trillin’s recent tribute to his late wife, Alice, he recalls the moment when her good looks combined with her charm no longer allowed her to bat her eyelashes out of a speeding ticket. Something had changed for her. And she recognized what a loss it was. He recognized what a loss it was for her and her modus operandi. But to him she was still the beautiful Alice.

That ability to find the immutable character beneath the outward appearance is a marvelous ability that lets us continue to love who we love, no matter how changed they become over time. People go from babyhood through childhood, adolescence and into maturity, changing all the while, and incorporating those changes into their identity, usually without too much problem (except perhaps during adolescence, when those changes plus raging hormones lead to lots of risky behavior).

Women’s bodies alter during pregnancy, and yet they and usually their spouses can belt back the changes without choking.

The test of time

It’s only when we hit the downhill trajectory of aging that many people once again stop coping well with the deals their appearance hands them. Part of it has to do with what society values. We are such an ageist society, so enchanted by the energy and beauty of youth. So that passion for changing our appearance with surgery reemerges when the appearance no longer fits society’s evaluation of what is beautiful.

In some ways, I think the teenage acting out has so much to do with this too. The process of maturing into an adult involves things like acne (it’s right out there, on your face, afterall) and other unruly bumps and lumps that may not fit the projected version of maturing a teen may have imagined. And then there’s the fact of maturing mentally into a family that’s still wishing for that sweet child whose immature character was enmeshed in the family structure. At the point of maturing, that teenager is staking out their own, separate identity. It’s a scary turning point that combines a physical and mental transformation all at once.

The gold standard

When I was a teenager, growing up in a mostly Jewish neighborhood, girls were aided and abetted by their families in getting nose jobs, to become the American princesses of the media. Subjugation of identity to some societal ideal via plastic surgery is horrifying to me.

Also in the Triennial, Thomas Brummett, Nocturne #6, 2001–04, chromogenic print, 30 x 70 inches, courtesy of Schmidt-Dean Gallery, Philadelphia

Yet society seems to encourage it. When I turn on the Today Show, they seem to be talking on a regular basis about getting one sort of plastic surgery or another. In a way, they are imposing the (horrifying) standard of their industry on the larger culture. For them, plastic surgery means a longer life on the air. They are pressured into that culture by tv executives, but also by us, the viewers, who expect our tv personalities–and also our politicians–to look a certain way. And god bless her, Barbara Walters, has gone on looking pretty amazing with the help of the knife beyond all reason.

As part of a society where money counts, naturally people who trade on their good looks will try to preserve those good looks for as long as possible by nearly any means possible.

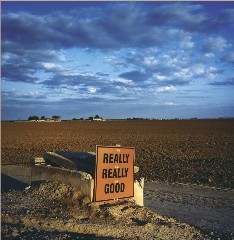

Also in the Triennial, David Graham, Stanislaus County, California, 2003, chromogenic print, 24 x 20 inches, courtesy of Gallery 339, Philadelphia

We all know people who have had face lifts, eye lifts. People change their hair color at the drop of a hat, or go from curly to straight and straight to curly. The more drastic changes get put in the context of what seems whimsical and good-natured girls-will-be-girls frippery. But it’s all aimed at identity shaped by conformity to some societal ideal (breast implants and liposuction, for example) or some generational ideal (I’m thinking purple hair and tattoos here). Certainly people in other societies do scar themselves or otherwise undergo unnecessary surgeries that set our Western teeth on edge.

Global views

That identity can be so tied to societal expectations is shocking. If I grew up in China or in the jungle in Africa, would I have had my personality snipped and tucked by social pressure to a somewhat different one than I have today, I wonder. And how about my appearance?

The miracle of all this is that our identity usually can incorporate the changes that life imposes on us, whether those changes be societal or physiological. It’s not always so easy. I still am shocked by the mirror or the photograph that shows how I look now, versus how I think I ought to look, used to look, imagine I look. I see someone who fights the fight to retain a glimpse of their physical past, and I feel guilty and disappointed in myself.

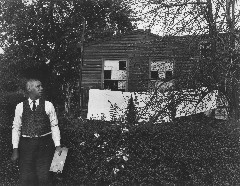

Also in the Triennial, Arnold Newman’s portrait of Horace Pippin, West Chester, Pennsylvania, 1945, gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 inches, collection of the artist

I went to a party and saw someone who I remember looking 10 years older than me in the past now looking 10 years younger than me, and I suddenly wonder if I’ve missed the boat on what is important. Because she looks younger, does it mean she is younger at heart, and that I’m as old as I look?

Infinite variety

Our society has stretched to accept a wide range of sexual preferences. In fact, society has always stretched for that, but just not in a codified way. It handled the variety by looking the other way most of the time. I mean, really, who didn’t know that Liberace was gay? People knew it and accepted it, but didn’t go face-to-face with the technicalties of the sex acts that it implied. As human beings, everyone got it–and didn’t get it, all at the same time. These days, with sex acts out in the open, people who would prefer to not go there are forced to go into the bedroom and confront the privacy of the sexuality.

I am not saying we shouldn’t be accepting or approving; I am saying that we have just changed the way that we are accepting, or not accepting, and the desire to have a public identity that matches a private sexual identity has won the day. But no matter how you slice the public identity, the private identity has been there all along and understood all along. So we’re back to the role that society plays in what identities it allows and makes public.

That we change our appearance to match our identity crosses lines at different places for different people. Our desperation to be who we really think we are can motivate us to do incredibly shocking things. But how shocking is a face lift in a society that says youth is more valuable than age? And how shocking is passing for white in a society that says light skin is a higher caste? And how different is it when a society of one says my identity calls for a sex change in a world where men mostly stay men and women mostly stay women no matter what their sexual orientation?

Truth in advertising

In a way, it all comes down to truth in advertising. I’m a guy, therefore I need to advertise it physically. I’m gay, therefore I need to be able to say it publicly. I feel younger than I am, so therefore I need to look it. But Sligh’s photograph of that white torso suggests that there is no truth in advertising, and that everything is a lie–the identity, the sex change, are all called into question.

Sarah Stolfa’s portrait of Joanna O’Boyle, 2005, pigmented inkjet print, 28 x 24 inches, courtesy of Gallery 339, Philadelphia

I find myself hoping that Jake finds true happiness as his and his doctor’s idea of a male. Certainly, the wedding picture at the end–our cultural idea of a happy ending–suggests he found it, at the same time that it raises questions. For there is Jake, all 5’2″ of him, proudly standing next to a woman several inches taller. Only Jake and his bride can say if this a marriage made in heaven. But as I presume Sligh intended, it raised questions about sex and roles, which of course brings Jake’s story back to Ellen Cope’s story, in which she becomes the young master, and her husband plays the role of her slave. In this case, the roles are temporary, and the two arrive in Philadelphia safely, where they find sympathetic people who then accept them, retransformed back to their original identities, as free people. Cope was in a position where she could pass, not as a man for very long, but as a free white person, had she chosen. She chose to retain her identity as his wife and as a woman of color–free, but in those days, in danger, even in Philadelphia.

Others in the Triennial

Others in the Triennial exhibit are Thomas Brummett, with his gardens based on a Japanese tradition of faux window landscape views; David Graham, whose ironic landscapes celebrate and laugh at the American scene; Arnold Newman, whose dramatic portraits recall a time when people dressed up and had dignity; Naomi Savage, who experimented with printing techniques; and Sarah Stolfa, whose Rembrandtian color portraits from the bartender’s point of view manage to capture dignity in people who aren’t dressed like Fred Astaire.