detail from Nontransparent Monument by Cai Guo-Qiang, showing airport security at work

Disaster is what has befallen us and made us into people we really don’t want to be. That’s what I got out of Cai Guo-Qiang’s installation group atop the roof at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see Roberta’s post here) and also out of Kara Walker’s exhibit downstairs in the contemporary section.

As Roberta mentioned, we were in New York Sunday to be part of a panel discussion on the effect of electronic media on art criticism, part of the International Association of Art Critic’s annual meeting (AICA, United States Section). Fortunately, I waited to get good and sick until after we spoke (although I think I was on my way, by then). But I was still running on all cylinders when we stopped at the Met.

Cai’s way with pyrotechnics and installation has always been a double-edged knife in the side of an alligator–something of beauty and something ephemeral along with something fearsome. But he has also been larger than the specifics to which he refers–crossing cultural boundaries and raising issues of placement in the firmament.

That little puff of black cloud in the sky, afterall, I took as a reference to the World Trade Towers disaster, so dark but only when you are close, and so powerful only when you experience the moment of blackness. Then, against the largeness of the sky and time, it dissipates. Only the New York skyline keeps its portent of disaster in focus as something terrifying. The presence of Transparent Monument beneath the black cloud to me only confirmed the connection to the World Trade Center. The birds smash into it and fall injured to the ground. Are the birds the victims jumping or the terrorists, this time defeated. The tower is see through, allowing a view of the sky, and not only of ourselves. For me, it worked as a wish for how things might have gone if we’d been a little different, if we could have seen a little more clearly.

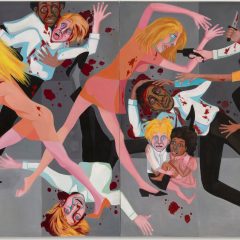

And then there was the Nontransparent Monument, a sort of comicbook narrative relief sculpture that packs in Stalin and Dubbya and everyone else, with security checkpoints at airports playing a large part in the long wall-sized drama. The three alligators (honest I don’t know if they were alligators or crocs because I still don’t know the difference), Move Along, Nothing to See Here, are mounted on bamboo poles like severed heads mounted on spears, pierced with sharp objects confiscated from airport security checkpoints. The objects include pen knives, knives from Ikea, knives with gold Asian characters embedded in the handles, butter knives etc.

This is large work, work that suggests we are hoist on our own petards, and therein lies the true after-effect of 9/11. For my Flickr set of Cai Guo-Qiang’s work, go here.

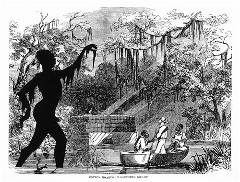

Kara Walker, Cotton Hoards in Southern Swamp, from the series Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), 2005

Offset lithography/silkscreen; 39 x 53 in. Courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

The snarling after-effects of a disaster were also vivid downstairs in Kara Walker’s installation, After the Deluge, a post-Katrina installation in which Walker hangs pieces from the Met’s collections with her own work. Sometimes, she borrows images from elsewhere, adding her own silhouettes as commentary.

Walker uses the sea image much the way Cai uses the sky, to expand the meaning of human events, but Walker’s take is not as optimistic. The theme of the sea is a long-standing one with Walker, who has long shown an interest in the Middle Passage. The deluge that overtook New Orleans was also unkind to blacks, unleashing a wave of fear and anti-African-American stereotypes at the same time that it re-exposed the cultural divide between white and black. It is at this divide that Walker has been working all along.

She also used in this exhibit less recent images that still fit the bill, like the silhouette of a black woman (a house servant or house slave?) holding at arm’s distance a swamp thing that’s really human–a black child with an alligator’s body–as a black man in livery bows obsequiously in the background.

By placing her work in the context of her artistic forebears, from silhouette cutters to Winslow Homer to popular magazine printmakers, and tweaking it to suit her own purposes, Walker once again demonstrates her mastery of turning culture back upon itself to face the issues that trouble it.