This time each year the Weekly sponsors an insert in the paper that supports the LGBT Equality Forum, the week-long conference that deals with gay issues. (The 2006 conference started Monday). The Equality Forum always organizes an art exhibition and usually I write about it for the supplement. This year I wrote a feature dealing with the issue of “gay closeting” in the art museum world. Here’s the link to the feature and below is the copy. Ant this link has the Equality Forum schedule

Museum Admission

A panel of experts makes the case for paying more institutional attention to GLBT artists.

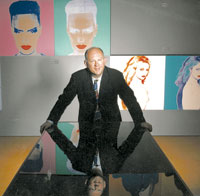

Warhol Museum Director Tom Sokolowski

Exhibitions by gay artists-even those as “out” as Andy Warhol-sometimes get mounted without any mention in the informational materials that the artist is or was gay. Though this suppression of information is less prevalent today than it was 10 or even five years ago, insiders say, institutions are still climbing the learning curve on how to address issues of tolerance and multiculturalism in their programming.

This year’s Museum Closet Equality Forum’s panel tackled the issue of LGBT information in the art world with a panel of experts who discussed how institutions could do better-and why they should.

“Generally, Equality Forum programming deals with obvious issues like hate crimes, but here we decided to look at more systemic problems,” says Equality Forum director Malcolm Lazin. “Think about it in terms of role models for gay and lesbian people,” he says. Institutions that suppress or mask the sexual orientation of LGBT artists make those artists invisible to students and other LGBT people looking for figures of empowerment.

Tom Sokolowski, director of the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh and a panel member, has direct experience with the issue. When he took over directorship of the Warhol from Thomas Armstrong, the museum’s first director, the Warhol’s walls were full of “oodles of information on Warhol’s history, his ethnicity, his religion-but nothing on his homosexuality,” Sokolowski says. One of the first things he did was put a text panel on the wall that dealt with Warhol’s sexual orientation. “To my mind, we feel it’s an important part of Warhol’s makeup-but no more so than his history, his religion, his ethnicity.”

Andy Warhol Camouflage self portrait and Victor Grippo’s Analogia I (second version), 1977, now on view at the PMA in Carlos Basualdo’s Energy Yes! installation.

Sokolowski has worked in several museums and art institutions. (Before Pittsburgh, he was director of the Grey Art Gallery at New York University.) He understands the complexity of the issues involved, and emphasizes it’s important not to sum things up in black and white. “It’s always about levels of gray,” he says. “If you have the courage of your convictions and a powerful personality, as I do, you can get things done.”

But Sokolowski admits things can be tricky with living LGBT artists-some of whom object so strenuously to mentioning their sexual orientation, they’ll forbid access to their works. “Even though the sexual aspects of their lives are well known,” he says, “if you want to show their work, you can’t deal with their sexuality.”

Jenni Sorkin, art history Ph.D. candidate at Yale and also a panel member, echoes that sentiment: “Some artists don’t want to be perceived or contextualized [as gay]. It’s a big issue.” Sorkin says artists have the power to withhold any reproductions of their images from the public if they don’t like the context in which the work will be shown.

Sorkin is also concerned about the lack of collecting of GLBT art by institutions, and how that lack of market value and institutionalization guarantees its exclusion from the history books. Feminist works from the 1970s, for example, like those by Carolee Schneemann and Judy Chicago, are rarely collected, Sorkin says.

“Carolee Schneemann is hardly collected. One piece from the 1990s was bought by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. It’s a newer piece, a photo of her French kissing her cat,” she says. This piece is less incendiary and more collection-worthy, apparently, than Schneemann’s earlier works, one of which, Interior Scroll, involved a performance in which the artist pulls a long string of text out of her vagina.

Strange Fruit (for David) (detail), 1992-97; by Zoe Leonard; fruit peel (orange), thread, needle, variable dimensions. Photo by Vivien Bittencourt from a 1995 installation at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Contemporary lesbian artists like Nicole Eisenman and Zoe Leonard are faring a little better. “They’re hip lesbians,” Sorkin says, adding that both are also object-makers, as opposed to performers like Schneemann and some of the other ’70s feminists. The Philadelphia Museum of Art owns and has exhibited works by both Eisenman and Leonard.

Funding is a big issue in mounting shows by artists whose works are seen as difficult. “Boards are fairly conservative and don’t want to rock the boat,” Sorkin says, adding that with NEA money so scarce and private collectors not invested in the work, it’s hard to get funding to put on shows. But “the beauty of an oppressive cultural environment is that a lot of great work gets produced,” she says. “I do have hope for museums changing.”

Nicole Eisenmann’s “Untitled” 2004, a watercolor on paper, exhibited at Art in the Armory 2005. Thanks James Wagner for the image.

“Big museums,” says Sokolowski, “the Museum of Modern Art, for example-have chosen to create a canon of what art is about. And not only homosexuals, but women, minorities and figurative art don’t fit into that. It’s the deracination or desexualization” of the story, he says.

Sokolowski says he hopes the LGBT community seeks alternatives to the hierarchical modes that predominate today. “We see gay people aping the roles of the straight world, but we want to create alternate systems. What we should be learning is to be more horizontal … to include more people and don’t just talk about who has the biggest stick at the moment.”

And that’s great advice-no matter what your sexual orientation.