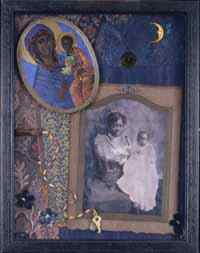

Midnight Madonnas by Betye Saar

The exhibit Extending the Frozen Moment at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts has a pretty interesting premise–to recontextualize photographs of African Americans, thereby redefining the people in the photographs and pulling them and their peers into the heroic story we tell of our culture.

The work, about 60 pieces, is by Betye Saar, one of a generation of African-American women who overcame with grit and spirit and fine art the white male bias of the art world in the 1960s.

Photographs and found African-American and family memorabilia are key in the pieces, which are mostly framed or boxed assemblages. While some of them haven’t stood up over time, and give off the depressed, figurative scent of a thrift shop, others of them bristle with their theme of race. Sometimes they are subtle. Sometimes they are didactic and without poetry. Sometimes they are obscure.

My personal favorites were extremely different from one another.

Blackbird is a third grade class portrait from 1911 of African-American children. The photo is mounted with a vintage blackboard/school desk, and includes imagery of blackbirds and watermelon-eating dark-skinned dolls. Each child, an individual, stares out earnestly, filled with promise. The picture is a tender mother’s keeper at the same time that it serves as a reminder of broken promises and broken promise. The magic to me of this photo is its ability to deliver the message with complexity and depth of feeling all at once.

Sambo’s Banjo, in which a Sambo puppet hangs near a photo of real lynching–both inside a banjo case that’s painted on the outside with a stereotyped Sambo portrait that includes googly eyes and bling-decorated teeth–is breath-taking for its beauty, its directness and its horror. For all its harshness, this 1971-2 work also manages to deliver an undercurrent of complexity, a suggestion that all is not black and white.

The young artist Jeff Sonhouse drinks from the same stream that feeds this work. And so does Kara Walker, although this comparison might upset Saar, who, with Howardena Pindell, criticized Walker for using exaggerated, derogatory racial images that pander to white prejudices. In addition to the Walker and Pindell links above, there’s a summary of this issue on the Deutsche Bank site.

Other pieces that interested me especially–The Band at the Libya, partly for its nostalgia and the name of the club, Sentinel, partly for its materials, collage on a handkerchief, and Miss Ruby Brown for embodying past femininity in a red glove.

I admired the concept of challenging and rewriting the photographic record and Saar’s early understanding of just how unreliable photographs can be. I also admired the persistent theme of questioning and reworking our images of race. For those reasons, this exhibit, put together by the University of Michingan Art Museum, should have been a better show and should have been a must-see show. Some hard-minded editing is required here.