Joel Meyerowitz speaking at the Philadelphia Free Library on Tuesday.

Steve and I and our friend Ann went to hear Joel Meyerowitz speak at the Free Library Tuesday night. Meyerowitz, a photographer known for his pioneering color street photography of New York (he was in Kate Ware’s awesome Mavericks of Color exhibit last year at the PMA. See artblog posts here and here.) talked about his book new “Aftermath,” which depicts his eight and a half months of photographing Ground Zero after the 9-11 tragedy.

Meyerowitz’s talk never dipped into maudlin sentimentality but was instead full of ideas about history, archiving, photography and of course the people he met. Here are my notes from the talk. I’ll keep it in first person for the immediacy of his voice.

Jan. 1, 1983. Shot of lower Manhattan from the artist’s studio.

Preamble

September 11, I was on Cape Cod. It was 6:30 am on a beautiful morning and I was up working. I thought how quiet it was. It was serenity itself. I thought how good life was. Then later the cell phone rang and my wife said “Get to a tv.” I did and saw the second plane hit the tower. I packed up my gear and started to go to New York. I wanted to be of some help. But I couldn’t get to New York. They closed the city for four or five days.

I lived not far from the World Trade Center in the West Village. I didn’t like the towers but, like everyone, I got used to them.

When I got back to New York I unpacked and went down to as far as I could get—4 blocks away. Already the cyclone fences were up with tarps over them. You couldn’t see anything.

No photos buddy

I always have my Leica camera. It was on my shoulder. I raised it to my eye. At that moment my life changed. A woman police officer poked me in the back and said “No photos buddy. This is a crime scene.” Being a born New Yorker I don’t take crap from the police. I said “Suppose I was a member of the press corps what would you say?” She pointed way back half-way up the block. There was the press corps corralled around this big tree. I said “When are they going in?” She said “Never.” As I walked back and passed the press corps a light bulb went off.

I thought, I can go in there and make an archive. Without an archive there is no history. I was so enraged at that moment that I acted. One thing led to another. I called the Museum of the City of New York. Could they help? I said I’d give them the archive. That began the task. I managed to work it out by hook or crook, mostly crook. I forged every pass I ever had to get in to Ground Zero over the 8 and 1/2 months I was there.

The press material (for the book) says I was the “only photographer to have total access to Ground Zero.” No. That is pr. I didn’t have permission from Rudy Giuliani. It was a struggle every day.

Looking South

In the summer of 2001 I was preparing an exhibition “Looking South” New York city landscapes from the studio over a 15-year period. All summer long I had these pictures in the studio in Cape Cod. That might have been part of wanting to do something useful. The pictures show the “Big Sky” country of Manhattan seen from my studio. They show that it’s an island on the edge of the ocean, something you mostly don’t see.

Sept. 5, 2001 I was in New York to work with the lab and I went to the studio and took another picture. It was not so great and I thought “I’ll come back. It’ll always be there.”

Going in

From World Financial Center looking east.

On Sept 23 I entered Ground Zero. I had a worker’s pass from the Commissioner of Parks, Adrian Benepe. He was a friend. When I initially called him I said “Who do you know in government that would give me a pass? “ He said, “I am the government.”

Ground Zero was a pile of rubble 8 stories high and another 7 or 8 underground. To recognize 110 stories of building that was 15 or 16 stories of compressed steel, the enormity of that left me quivering. I was crying and shaking and it never really left me. Every time, I had a sense of how profound the space was.

Steel from the North Tower thrown into surrounding buildings. “The WTC was a hull and core construction. The hull was tridents of steel bolted in place. 200,000 of them, everywhere, and they were hurled everywhere (like spears)when the towers came down.”

Beauty and being thrown out

I was thrown out two or three times a day, everyday, and I would get back in. I was there 12 hours a day.

Two police officers said to me, “You gotta go.” I showed my badge and letter. They said “It doesn’t matter, the chief said you gotta go.” So I left. Coming out, it’s October, a beautiful day. There’s sun on my back and I’m feeling that it’s good to be alive. But it’s a charnal house in there with 3,000 dead. I can’t leave. I have to photograph it.

Nature is indifferent to what’s on earth. There will always be beautiful days and horrible things.

So I go back and a firefighter stopped me and said “No photos.” I said I was just talking with Fellini (the chief) and the firefighter said “Ok” and let me continue.

So every day I asked “Who’s the chief today?” And then if anyone wants to throw me out I’d say the chief’s name and how I talked to him.

Why no photographs?

Why did they not want photographers in there? Fear. 343 firemen died. There was fear of sensationalism. Also the city didn’t want to appear to be making money off this. And, it’s easier to say nothing.

I made a deal to make this not for profit archive and give it to the city. I wrote the Mayor. Told him the idea of the archive in the context of the Farm Security Administration photos. He never responded. We sent him a book and never heard back. Has the mayor commented? No. And he’s an amateur photographer too. He has a Leica!

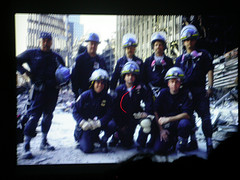

The Arson Explosion Squad

The Arson Explosion squad, sorry it’s fuzzy.

The Arson Explosion Squad is an elite squad of detectives. I owe them.

One night I was photographing and was backing up on a pile of rubble. There were these guys sitting on top of the pile – on chairs. (There were chairs everywhere at Ground Zero). I thought, that’s the best place for my shot. I have to go there. So I went up there and did a spontaneously dumb thing, I sat down on this guy’s lap and said you’re sitting in my seat! They all got up and said excuse us. I talked with them and said how much trouble I was having and how I was getting kicked out. They said we can help you. Here’s our cellphone numbers. We’ll protect you. So every time I had trouble I’d call them and give the person my cellphone. You could almost see the stream of invective coming out through the phone! It worked.

Iron Workers

Ironworkers

Thousands of iron workers were there to cut up the stuff. It was like walking in a field of razor blades and they were fearless. Many were wounded in the work but nobody was killed. Many of them had worked on the original buildings.

One night I saw everybody running. I followed and worked my way down to a light. There was a void into the rubble. They had found an intact stairwell. The firemen came out and said this stairwell was in the North Tower. Five firefighters bodies were in it. Intact. Everyone imagined them flying down to the ground in the stairwell. We imagined their deaths.

Smoke and water to put out fires.

Ground Zero was 16 acres and four square blocks. There were 72 big machines, 6 gigantic cranes, hundreds of trucks. The noise was amazing. Each time they pulled out a piece of steel (they called them sticks) there was a hole in the rubble and oxygen rushed in and ignited a fire.

Heaviness of memorial objects

In November the city opened Ground Zero and allowed families to come in for a memorial service. No politicians. Just singers, etc. As the famiklies left they gave mementoes (flowers, pictures, stuffed animals) to the firefighters and asked them to put the mementoes on the site. The firefighters would look at the mememto, study it closely, look back at the family member and then carry it, like in procession, and place it on the site. The compassion was vivid.

Firefighter placing memento from the families at the site.

A rabbi and a priest were there (this sounds like a joke, I know). They asked me to put a memento there. It was the heaviest thing I ever carried.

A woman saw this photo in my show in Provincetown and recognized her memento in it (a picture of her daughter). She called me up and said I put something behind the picture for you. I looked behind the picture and it was a copy of the same photo that was in my photo.

Pia Hoffman. There were very few women doing heavy lifting. She’s a licensed engineer and can drive any machine. One night she was operating a grappler and she discovered remains of a woman. When remains were found they’d always shout “Flag or Bag?” If it was Flag, it was a police or firefighter and they’d carry the person out in procession. If it was civilian it was “Bag” and it was plain and simple. So she called out that she found remains of a civilian and wanted a flag. They didn’t want to do that. “You bring a flag and an honor guard or she’s not going anywhere,” Hoffman said. From that day forward civilians got the same respect as the rescuers.

Worker in a raking field

My most consistent image of people at Ground Zero is people on their hands and knees sifting and looking.

The last night

The last night they saved a column to be the symbolic last body and brought it out in ceremony. The last time I went, June 21, it was silent and empty. I had the whole place to myself. I was there remembering. I made 8,500 images.

Health

I have a tickle in my throat. But I know many are sick. Like the 12 Arson Explosion Squad members.

Other photographers jealous?

Meyerowitz

The other news and press people were mad as hell. Some Magnum photographers asked me how could I do that? I said I’m giving it away and you’re for profit. Some people wanted to interview me at the site just to get access. I wasn’t going to do that.

Self-effacement versus editorial point of view

In my aesthetic approach I was trying to use self-effacement. In other words, usually you’re self-absorbed and show your stance. But if I was going to be historically directed I didn’t want to have an editorial point of view. I understood my own behavior had to be invisible so you the viewer can see what I saw.

I felt a change in my approach for this task. And it’s changed my working methods. I feel like doing socially-useful work. I now feel that horrible things are photographable. I always knew it but this taught me that clearly.

Disaster nostalgia

I have a powerful emotional connection to this place. But it changed over time. By March they were down to bedrock and the pile diminished into a hole. There was a strange feeling of nostalgia. People would say “Remember in October when we found…” We knew it was coming to an end and there was sadness. In a few months they’d be back building shopping malls. Now they were finding people. I remember thinking Oh my God it’s almost over. What am I going to do when it’s over?

The Memorial

I felt very close to Liebeskind’s overall plan. His sense of the voice of the site was humanistic. He wanted to keep the slurry wall. It’s a heroic wall. It keeps the river out. Without it Lower Manhattan would flood. The power of that wall — it felt like the Pyramids. I’d like to plant trees. One for each of the dead. Especially pine trees with their scent. It would be a great reforestation of Lower Manhattan. I would have kept the rawness. Now it’s been modified out of hand. The monument will have power even if it’s design-y. It will carry the message.