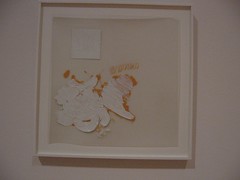

To Gertrud Mellon

1958

casein, graphite and colored pencil on paper, 11 3/4 x 12 1/2″

The 26 small works exhibited by the maestro of the blizzard of white, Robert Ryman, at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts turned out to be somewhat of a revelation for me. So was Ryman’s brief talk Wednesday, given in conjunction with the exhibit, Robert Ryman: Small Works.

This pair of events is a coup for Curator of Contemporary Art Alex Baker. After all, Robert Ryman is not only a major artist who rarely speaks, but his presence at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts can be seen as a symbolic storming of the walls of the academy. The events are matched to the recent Ryman permanent installation Philadelphia Prototype in PAFA’s new Hamilton Building–which is perfectly sited there.

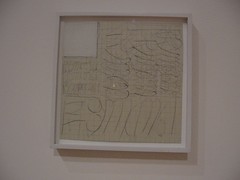

untitled study, 1960

oil on mylar panel, 10 x 10″

The little paintings, on exhibit in the Morris Gallery, which is free and open to the public, feel fresher than the large works that dominated the Robert Storr-curated retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 1993.

Oh, white still dominates here. And predetermined, repetitive strokes still drown some of the paintings. Every once in a while I wondered, does this guy look at and revise what he’s doing? But many of the small works looked like quite the opposite. They look utterly investigative.

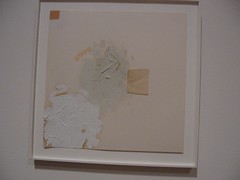

untitled, 1960

casein and graphite on tracing paper collage on Bristol board

10 7/8 x 10 7/8″

Ryman is man who has chosen to focus on material, and the materials clearly pose challenges that he rises to with a vengence. The paint appears on naked supports–linen, mylar, paper, a coffee filter–with a stubborn vigor and scrawl that surprises. The works also include collage roughly layed down with an eye toward translucency and its properties. Even Ryman’s signature use of his name as a compositional element, which looked so egotistical and annoying printed across large pieces at MoMA, here looks like it comes straight out of Sister Gertrude’s page book, hand-written and wonderfully inelegant.

The tamest of the works were the artiest, the graphite and charcoal on gray paper with drawn-in grids. The wilder the work, the better.

untitled, 1961

graphite, charcoal and pastel on gray paper

10×10″, one of the wilder of the graphite on paper pieces

Some pieces reminded me of Jasper Johns flags, Mark Rothko emanations, Robert Motherwell balancing calligraphs, and Hans Hofmann colliding rectangles.

But ultimately, I came away with the thought that Ryman is not a painter’s painter. He’s a curator’s painter. He’s playing to the issues curators discuss–the edges, the mounting, the surface coating, the surface beneath–the material properties–allowing for easy discourse.

But that choice results in a painting that is merely about the properties of paint and other materials. It’s a big world, and Ryman has chosen to ignore it, just as he has chosen to ignore the full color palette.

I am not saying I don’t find the sheer crankiness of some of his paintings wonderful in their revelation of character. But I do think he is not interested in how his paintings reveal his character. He is only interested in how the materials express themselves.

Henri Matisse’s La Danse, first version; in this one, Ryman said the painting was telling Matisse what to do.

Ryman’s talk lasted only a few minutes. “A painting is something that’s never been seen before,” he said. That was a good one. He also mentioned the obvious one for a man who’s all about materials–that you can’t see a painting on a computer screen. “You have to see the real thing.”

He then said you have to know the rules for painting–aesthetic rules and technical rules–in order to do a painting. He did not reveal what those rules were.

Henri Matisse, La Danse, later version; in this one, Ryman said Matisse was telling the painting what Matisse wants.

But he did show several images of work by Matisse that he admired, as well as a Mondrian. He ascribed aesthetic perfection in the choices of shapes and colors in the two Matisses he showed at first. He discussed the difference of paintings that you can look into, a la Matisse, and paintings that go outward from the wall and into the space of the room, a la Mondrian, with its painted sides. “You can’t experience it on slides,” he said of the painted sides.

He also discussed the differences between two versions of Matisse’s La Danse. In one, he said, the painting is telling him what to do–it’s an open investigation during the process of painting it. In the second, Matisse was telling the painting what he wants. Interestingly enough, Ryman seemed to prefer the former, although it occurred to me that was a position often at variance with his own practice.

Ryman behind the podium looked a bit uncomfortable, dressed like a lower-management guy in his business suit, his hair pomaded into place. He had difficulty hearing the questions during the brief q&a. Mostly I couldn’t help think that he had found silence served him better than talking in an art world that talks far too much. Of course, that leaves lots of room for happy curators to say what they will say.

And speaking of happy curators, more kudos to Baker, who has installed in the stairway hall, outside the Morris Gallery, works with lots of white by Thomas Chimes, Monique van Genderen, Barry Goldberg and Kevin Finklea (the latter newly acquired). They look great, and go in completely different directions from Ryman, although Finklea and van Genderen raise the issue of how a painting can talk about material and yet manage to talk about something else at the same time. They also deftly place contemporary practice in the stream of academy values and practices. along with contemporary practice. (For images of these and more Ryman’s go to my Flickr set).

P.S. While I looked at the Rymans with art historian Andrea Kirsh, she said it would be better to see them during daylight–a good call that applies not only for the exhibit in the Morris Gallery but also for the installation in the Hamilton Building. Since winter is approaching, 5 p.m., closing time, will be too late soon.