My strategy for visiting a museum is generally to spend no longer than an hour, maybe an hour and a half. But sometimes you have to break your own rules.

Kindred Spirits, 1849. Homage to Hudson River School painter Thomas Cole and nature poet William Cullen Bryant. On loan from walton Family Foundation. National Gallery.

I had forgotten how big the National Gallery of Art was and forgot also that to walk from one end to another –without stopping to look at anything — would take a good 15 minutes. So my 90-minute rule went out the door and I took the museum as it came, letting myself be drawn this way and that. In my whimsical wandering I happened on Asher Durand’s Kindred Spirits, on loan from the Waltons and on view at the museum until Feb. 2007. I’d seen the famous painting in homage to Thomas Cole in the American Sublime exhibit at PAFA in 2002 (the show was organized by the Tate Museum) and thought it was a great work. So I stopped and looked for a while. The museum’s free pamphlet which explains the story behind the painting — about Cole having died and Durand, inspired by the poet William Cullen Bryant’s oration at the artist’s funeral, painted the work of imagination in which Cole and Bryant take a hike together in the mountains. There’s a nice brochure that explains the story but unfortunately the color reproduction of the painting is a flight of imagination, too, making the work both darker than it is and bluer.

Augustus Saint-Gaudens, Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Regiment. Patinated plaster. 1848-1907.

On my ramble, I was drawn in by a dramatic gilt and bronzed plaster relief sculpture, the Memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the Massachusetts 54th Regiment by Augustus Saint-Gaudens. The work, made of 51 separate large and small plaster pieces is the same as the bronze memorial on Boston Commons (1897). Here in the National Gallery, the work, patinated in gold and bronze the way it would have been shown in the 1800s, is in a small chamber which accentuates its drama as a work of narrative power and historical import. The work is newly conserved, and this is its 9th showing since its making. The museum’s website lets you take a virtual tour of the piece.

Studies for Robert Gould Shaw memorial

Visitors were posing in front of this work just as they would in front of an outdoor monument or attraction. However, the cramped quarters made for a constant patter of “sorry” and “pardon” as photographers and posers backed into each other by accident when taking the shot.

after Giovanni Bologna

Mercury, c. 1780/c. 1850

bronze, 177 x 48.5 x 94.9 cm (69 5/8 x 19 x 37 1/4 in.)

Andrew W. Mellon Collection

1937.1.131

The piece that really surprised me — and I’m guessing it’s because it seemed the most non-American work in the American museum — was the Winged Mercury statue in the fountain near the West entrance, a piece of voluptuous Italianate statuary whose gorgeousness is foreign in the way that the no-nonsense realism of St. Gaudens piece is quintessentially American.

I had just been reading an article about the Rennaissance sculptor Giovanni Bologna (called Giambologna) and the article in the Sept. 21 NY Review of Books had a photo of the master’s Mercury statue (c. 1580) and while I couldn’t believe the National Gallery had the Giambologna Mercury it did look like the same piece.

Anrew Butterfield, who wrote the Giambologna article, talks about the artist, who lived at the time of Michelangelo and made many pieces for the Medici family, as someone who took his Medici commissions seriously at a time when other artists just cranked out work in quantity to fulfill the contract. Charged with making statues for the Medici gardens, says Butterfield, “he virtually invented the fountain statue as a subject for high art.” Apparently the Winged Mercury was one of these fountain statues.

Giambologna did a brisk business in Florence in small statuettes, something that hadn’t yet caught on as interior decor. Giambologna’s genius with the little, palm-sized works was to make them objects of sensuality and beauty. Venus after her Bath is a work more about sensuality and beauty than about mythology or story-telling.

Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao Spain

America doesn’t have a Giambologna but of course we never had a Rennaissance either. American art is tinged with pragmatism and puritanism and other things, But the idea of sensuality and beauty that drive the Giambologna works are not part of the American recipe for art. Does Edward Weston count as an American sensualist? Does Lisa Yuskavage? Maybe Frank Gehry is our Giambologna, his undulating, Titanium-clad buildings do seem to be statements about sensuality — an idealized, pure and not quite human sensuality but a feast for the senses nonetheless.

The museum’s website — which is great on provenance — lists the Winged Mercury as “after” Giovanni Bologna, and dates it to c. 1780-1850. So it’s the same basic object just made by someone other than the Rennaissance sculptor.

East Wing

Waterfall in the underground concourse between the West and East wings of the National Gallery.

Speaking of Gehry, as all Philadelphia is dreaming about Frank Gehry’s stealth underground makeover of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, announced by the PMA last week, I want to be the first to say that no matter what Gehry and the museum do underground in the mothership building they’re missing an opportunity if they don’t put an underground walkway between the building on the hill and the new Perelman building which will house galleries for sculpture and for prints, drawings, photography and costumes. Perelman is targeted to open next summer, and the building, which will also house the Director’s office and meeting rooms, sits across treacherous Kelly Drive. Visitors as well as the museum’s trustees and administrators would be well served by a passageway/concourse beneath the street. Can’t we have a waterfall, too?

The concourse beneath the National Gallery and the East Wing works just fine. Not only does it provide safe underground passage between the two buildings but they found a way to make a profit center out of it, putting a cafe and restaurant down there along with the museum shop. There’s a waterfall and a moving sidewalk to boot and while that makes it one iota away from a glorified airport terminal, the underground idea is a good one.

Lobby of the East Wing which houses the modern and contemporary collection and temporary exhibitions. On the back wall is Ellsworth Kelly’s Color Panels for a Large Wall, 1978, oil on canvas. On the shelf next to the Kelly is Anthony Caro’s National Gallery Ledge Piece, 1978. welded steel. I give both works A+ for their deadpan titles.

I ran into an entire room full of Guston paintings and works on paper in the East Wing and that was an unexpected treat. The works are part of the Broida Collection of 62 paintings, sculptures, and works on paper by twenty-three artists given to the museum in 2005. The Broida Selections (37 objects in all) are up until Nov. 12.

Philip Guston

Rug, 1976

Gift of Edward R. Broida

2005.142.19

Constable’s Great Landscapes: The Six-Foot Paintings is on view in the East Wing. The show is a great one, and what stands out most is the hanging side-by-side of the six-foot sketches for the paintings and the finished paintings. And the news is…the sketch is more appealing to a contemporary eye than the finished work. What the sketches have are these contemporary characteristics: vigor, hesitation, exploration and doubt. The finished work has pristine edges and feel of inevitability.

I couldn’t take pictures in the Constable exhibit but here’s the Rachel Whiteread piece outside the show in the lobby area.

The crowd in the Constable show was big and the gallery spaces for the show are not so big, and it made for some frustration as I bobbed and wove and tried to see up close then stand back for the grand view. The show spans two floors and if you’re looking for elevator access to go up or down you’ll have to retrace your steps to the main lobby for that. Otherwise there’s a nice stairwell between floors tucked inside the galleries that will get you around. Here’s ionarts‘ post on the show.

Andy Goldsworthy, Roof, 2004-05. Buckingham Virginia Slate. (9 hives in all) National Gallery, East Wing, outside the window

Andy Goldsworthy site specific piece Roof, a new permanent piece for the museum, snuggles in to a window well on the north side of the building. The piece has an indoor presence as well as it seems to break through the window and settle itself on the floor inside. It’s a great piece, almost impossible to photograph from the inside.

Martin Puryear: Lever No. 3, 1989, carved and painted wood. Robert Motherwell: Reconciliation Elegy, 1978, acrylic on canvas. These two pieces are beautifully sited. In fact a lot of the sitings are beautiful–in a Barnes-ian way, the rhythms of one object echoed in another work nearby. National Gallery, east wing.

I love the pairings. Whoever set up this Martin Puryear near the Robert Motherwell had a good time. It’s totally inspired.

Martin Puryear, Jackpot, 1995. Canvas, pine, hemp rope over rubber, steel mesh and steel rod. Broida Collection. national Gallery. Background left is Jean Dubuffet. Right background is Frank Stella.

Here’s another Puryear piece, part of the Broida Collection. I love its siting too.

And furthermore

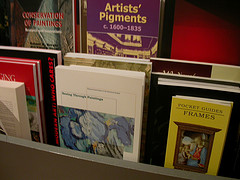

Seeing through paintings, by Andrea Kirsh and Rustin S. Levenson, on display in the National Gallery shop.

I told artblog pal Andrea Kirsh I’d seen her book, Seeing Through Paintings at the National Gallery store and she told me book deals with many paintings from the National Gallery’s holdings, so it’s no wonder.

Butterfly Garden

I needed some air before getting on the bus home so strolled up the street past the sculpture garden and right into the Butterfly Garden to catch the flowers (no butterflies at 6 pm in October).

Hirshhorn Museum

Finally, some combination of late afternoon sun, cast shadow on the round Hirshhorn Museum and red car parked smack in the middle caught my fancy. Washington was full of people that day and here, for a second or two, are vestiges of folks but no warm bodies. I didn’t notice until I looked at the photos later that this red car has a big dent in its side, a reminder of why much art (like the Lichtenstein in the background in this photo) seeks perfection. It’s because we don’t have it so much in the rest of our lives.