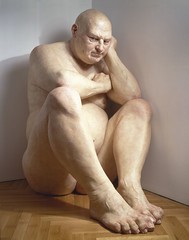

Ron Mueck’s Big Man seems like a quote of Lucian Freud’s big-man model, Leigh Bowery. The two artists certainly share concerns about flesh.

Mixed Media, 2000

81 x 46 1/4 x 82 1/4 inches (205.7 x 117.4 x 209 cm)

The side show quality of Ron Mueck’s giants and midgets, the Mme. Tussaud’s wax-works quality (the sculptures are actually made of fiberglass and silicone) keeps everyone looking at them agape. I was watching people watching at the Brooklyn Museum, yesterday. I loved this show, precisely because it is such a crowd pleaser.

But it’s more than a crowd pleaser. The astonishing scale choices and wax-work realism don’t really explain away the engagement that each of Mueck’s sculptures evokes in viewers.

Spooning Couple, 2005; these two are small, on a pedestal, Liliputian adults with Brobdingnagian worries, I’d guess from the open eyes

Mixed Media

5 1/2 x 25 5/8 x 13 3/4 inches (14 x 65 x 35 cm)

Private Collection, London

The exhibit includes 12 pieces according to the press release (I only saw 11) and a wonderful video showing Mueck’s process. You get to watch him modeling the clay and creating the molds, etc., and it is technically intense and laborious. You get to see his attention to detail. You get to see that he works with assistants. Yet you still come away with no real understanding of how he can do what he does; he has a gift.

You do come away with information about his materials, and his technique for applying hair. The hair is one of the things that make Mueck’s works startling. Not only are the figures not idealized. They have moles and wrinkles of all kinds. But they also have hair–head hair, arm hair, pubic hair. And they have accurate genitalia. They are a far cry from the romantic and idealized sculptures of the human form that fill art museums. The figures are no less lovely and admirable for their flaws and factual details. But the sculptures are 21st century human and vulnerable because of them.

The tour de force in this show (oh, heck, they were all tours de forces at least on a technical level) is A Girl, a baby so real and so big–15 feet long–that she’s awe-inspiring. She is just hatched, still coated with bits of bloody mucous, one eye shut, the other half-shut, her hair plastered to her giant head that, were it unsupported, would make her delicate, tender neck snap. This baby is not just a reminder of the miracle of birth and miracle of the child’s subsequent survival. Her scale is also a reminder of what a burden of responsibility each child is, what an impact a baby has on its parents, and how important that baby is in the parents’ eyes.

Crouching Boy in Mirror is at real-life scale. 1999-2000

Mixed Media

Figure: 17 x 18 x 11 inches (43.2 x 45.7 x 28 cm)

Mirror: 18 x 22 x 1/4 inches (45.7 x 55.9 x 0.6 cm)

The Broad Art Foundation, Santa Monica

Mueck can not be viewed adequately in pictures precisely because scale is such a key element. But the piece that surprised me most and intrigued me most was the only one to natural scale–Crouching Boy in Mirror. The mirror brings another dimension to the discussion about realism in these sculptures. The mirror becomes the unreal space–of a mirror, a painting, a television screen, a movie screen, a computer screen–and in that space, the boy looks even more real than he does in the 3-D world. The issue is about more than dimensionality. It’s about our buying into the reality of the fictional worlds we create, about the depth of our suspension of disbelief in those 2-D worlds.

Two Women, 2005

Mixed Media

33 1/2 x 18 7/8 x 15 inches (85 x 48 x 38 cm)

Collection Glenn Fuhrman, New York

Not every piece interested me. I wasn’t all that interested in Two Women, even though I admired the accuracy of their bent posture and their relationship to Bill Viola’s The Greeting and Jacopo da Pontormo’s Visitation. But making two elderly women small does not seem all that interesting an idea. The Man in Boat barely rises above cliche. The figure’s nakedness and his small scale in the gigantic boat are not enough to overcome that cliche. But his arms are crossed as if he’s waiting in line, his face is peering toward something he can’t quite figure out, and his hair is 40s movie-star glamourous. I suppose it’s not Mueck’s fault that I’ve been poisoned by Bo Bartlett and Andrew Wyeth–or maybe it is.

Mask III, 2005

Mixed Media

61 x 52 x 44 1/2 inches (155 x 132 x 113 cm)

Private Collection

I also found Mask III, the face (and ears) of a heavy-set black woman with velvety skin and juicy lips, somewhat troubling. Why make a her a mask? I wondered. Is it a salute to African masks? or is it a stereotype? or is it about stereotypes? Or is it a political statement about wearing public masks? And don’t we all? Or is it only about trying out another skin color, another hair texture, and if so, why would it be so large? The pleasant expression on her face seems to contradict the stereotype theory, and her eyes seem expressionless. Is it about her power? I’m left to wonder, without an answer.

Each of the pieces has something unsettling about it. I suppose, besides the trick of extraordinary realism, that it’s why I liked the exhibit. Clearly, I was not alone.