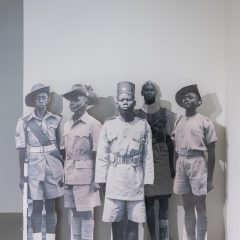

One of comic strip artist R.Crumb’s sketchbook pages; all these photos of Crumb’s sketchbooks supplied by Rosenwald-Wold Gallery

Before I get embroiled in the silly stuff that sets my mind spinning, I need to say that for R.Crumb fans–I’m one of them–the show Robert Crumb: My True Inner Self at Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery offers more than just a review of the range of his comic book drawings, but also a mix of his cartoons and drawings on things like napkins and paper towels and other non-standard drawing surfaces.

Crumb is one of those obsessive guys who has to express what’s on his mind, and the more it irritates people, the more he has to express it. He came along in a time when doing that was de rigeur politally and socially, the ’60s. If he’d come along now, he might have been quickly repressed by the Bushies, except maybe he’d use the Internet to broadcast what in those days was broadcast by underground comics and alternative newspapers.

I think of Crumb as my people, my generation, and I love that he’s got a young following now. (Although I often marvel at how the tastes of the ’60s are so popular right now, from bell bottoms to communes, I’m not so sure that the spirit of rebellion is more than skin deep; only the repressive politics of W. are keeping the spirit alive, I suspect).

I remember poring over ZAP comics and Mr. Natural and all the scatological and stoner humor as a legitimization of the “freak” world that we felt was ours. It’s the verso of Little Orphan Annie, with Mr. Natural being the anti-Mr.Am. But even then, it was clear that Crumb was wilder by a half than we ever were, though we fancied ourselves on the edge of civilization.

Crumb’s drawings insult nearly everybody. Any number of activist groups have taken offense at his work.

I was lucky the day I stopped in at Rosenwald-Wolf and caught a class viewing Terry Zwigoff’s film Crumb. So I joined the group and watched the second half with them. It sort of sputters along, sometimes fascinating, sometimes draggy, but worth the watch. (Yes, you can rent it yourselves).

BTW, the show includes a local reference. One of the pages displayed is from Yarrowstalks, a Philadelphia underground newspaper of the time.

In all of this, though, my heart went straight out to his drawings on blue-lined notebook pages–you know, the marble-covered notebooks that kids write their school notes in before they graduate to spiral-bound and then looseleaf notebooks.

Using this kind of notebook for a sketchbook is right in keeping with his drawings on napkins and then saving them.

The downside is evident in what happens to those drawings. The notebook paper is so acidic that it is starting to turn to brown. The rate of change is stark, emphasized by the Wite-Out corrections in the drawings. The Wite-Out, true to its name, is white, white white. The page is white no longer.

Now Crumb probably never gave the staying power of Wite-Out a thought when he used it. After all, who knew that Wite-Out was more archival than marble-covered notebook paper? I sure didn’t. I never gave the archival qualities of Wite-Out a thought. The then-invisible corrections flash neon on the muted page. Of course, Crumb probably never gave a thought to the archival qualities of marble notebooks. (A friend of mind who owns The Framer’s Workroom in Jenkintown recently told me that archival matting is less than 30 years old)!

What he must have given a moment or two’s thought to was how funny to interrupt the blue-lines pattern in the course of making a correction. After all, those blue lines were already there, and the correction was not so invisible, therefore, right off the bat.

I know I’m once again writing about everything but the excellence of R.Crumb. It’s just that in my world, his excellence is a given. He’s legitimized nerdiness, teaching the culture how to absorb computer geeks before they were twinkles in their daddy’s eyes. And he’s father to social geeks in comics like American Splendor, by Harvey Pekar, and Ghost World, by Daniel Clowes (the movie based on the comic book also was directed by Zwigoff, by the way). Crumb is pretty thoughtful, with a kind of existential wonder and cynicism all mixed up together. All his outrageousness is nearly a by-product of a mind that’s thinking about what it all means.