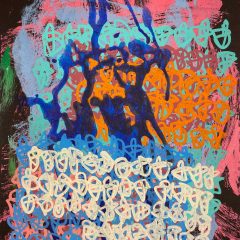

Verbena, by Rebecca Saylor Sack, oil on canvas, 60 x 70″

The four artists showing this month at Gallery Siano have such different takes on what a place can mean that the exhibit gathers meaning beyond the contributors.

Rebecca Saylor Sack’s extraordinary paintings of water and woods sparkles with light and energy and danger. In the flick of a brush, Sack expresses a branch or a tumble of leaves. The leaf mold underfoot, the glint of sky in water, the crash of broken limbs and trunks are all there as reminders of the peace and danger and the cycle of life and death in the woods–without ever using trompe l’oeil literal representations.

Sack, who teaches at Tyler and has a Tyler MFA, is one smart cookie of a painter. Her slashes of color bring to mind de Kooning, but without the hatefulness. Rather, the quick, bold marks express exuberance and joy–a love of nature and of place and of light–and a love of paint. There’s a baroque quality to this vision of nature, a suggestion of the outside as something to be viewed from the inside as well as something to be walked through.

The paint itself is a subject here, with its juiciness and harshness, its small agitated areas contrasting with its glassy, smooth surfaces. These paintings of arcadian landscapes and of space all by themselves make the exhibit worth a visit.

by Miriam Singer; these pieces range from 15 to 29″ as their largest dimension

In quite a different vein, Miriam Singer’s combination drawings and prints of cityscapes, have a maplike quality that reminds me of the outsider cityscapes of Friedensreich Huntertwasser. They are layered with colors and lines until they turn into places of Singer’s imagination. The drawings are distressed by her process. She carries them around with her, working on them every chance she gets. In the course of that, the work acquires folds and chewed away edges.

The layers of buildings become a maze for the mind as well as a journey through time.

Chestnut, by Catherine Gontarek, acrylic on canvas, 32 x 32″

Catherine Gontarek, from whose layered paintings bits of Philadelphia merge and emerge, seems to view the city around her through a veil. There’s a shiftiness here, in which the world is not quite to be trusted–a sort of magic that makes me think of traditional artistic nocturnes like Whistler’s Westminster Bridge nocturne. Here, bits of architecture almost define space and then fade back into night. Trees become quite stylized and Japanese, in this work, far more corporeal than the buildings behind. And the light sources glow in the fog.

The work has a romantic edge, a touch of the gothic, without succumbing to it.

Ms. Pac Man (Dots and Ghosts), by Alex Paik, 72 x 60″, acrylic on canvas

Alex Paik’s reductive maps express the empty spaces in video games at the same time that he seems to love them. Paik, who has an MFA from Penn and was one of the artists in Fleisher/Ollman’s Meat Ball exhibit, makes paintings with a cartoony quality, with pastels and disembodied symbols that pretty much mean nothing to someone who doesn’t know the visual vocabulary of the games he is quoting. At the same time that he is painting a big zero, he is painting a made-up land that he (sort of) loves. There’s a boyishness here, and a sweetness that reminds me of Japanese super-cute art (honestly, I didn’t say this because Paik is Asian).

Ultimately a pixel is only a pixel. It’s not exactly substantial. I get a sense from my conversation with Paik, that he’s on the cusp of mapping his way out of video game land, even though he said nothing of the sort. He just seemed a little doubtful. I’d like to see where he heads.