Matthew Pruden on Second Thursday at Nexus

After seeing Matthew Pruden’s exhibit, Magnetic Sleep, at Nexus, I caught up with him to ask a few questions. The exhibit is of a group of small, Victorian-looking photographs of supposedly supernatural phenomena, a terrific sound track of scary noises, and a projection from the eyes of a skull onto a screen.

The photos, which were inspired by the 19th century photos of spirits and other supernatural phenomena, are sly–just this side of believable. And the sounds are almost haunted house staples–but also just enough off to raise questions. A video projection from the eyes of a skull is not quite as successful.

This is part of his ongoing research in how ideas from the past linger and influence the present, and Pruden, who has been in Philadelphia since 1991 when he came here to go to the University of the Arts, previously has created exhibits on ideas like polar exploration, mountaineering and now spiritualism.

L. What made you create the work in your exhibit at Nexus?

M. It all comes out of my research into spiritualism, …the belief that the human personality continues to exist after death, and can communicate and be communicated with through the agency of a medium.

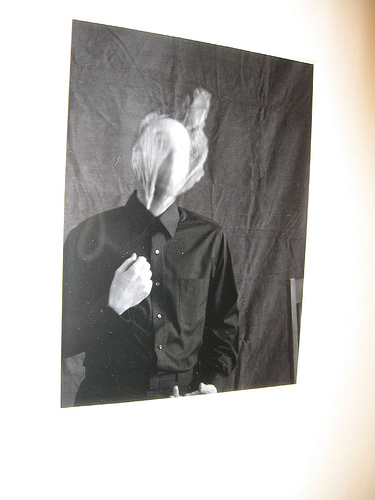

Metaphysical Forgeries: The Medium with Face Obscured by an Ectoplasmic Veil, by Matthew Pruden, inkjet print

L. How do you feel about that?

M. I’m a skeptic. But it almost doesn’t matter whether it’s fraudulent or not. The time period it comes out of I felt intuitively was pretty similar to where are now.

The 1860s…was the first time mass media were reaching the whole culture at once, [disseminating] the constant flow of anxiety about war.

Serious advances of technology were happening–like the telegraph, bringing nearly instantaneous communication. It was too fast for people, who were having technological fatigue in a way. Science was in its ascendancy. All this stuff combining with a mobile population to follow the factory work and a waning of traditional religion–people were feeling a lack of continuity.

The spiritualist movement was a reaction to anxiety generated by all these happenings. Science can’t explain everything away. But advances in communication technology were inspirational to the spiritualists. One of their newspapers was called the Spiritual Telegraph.

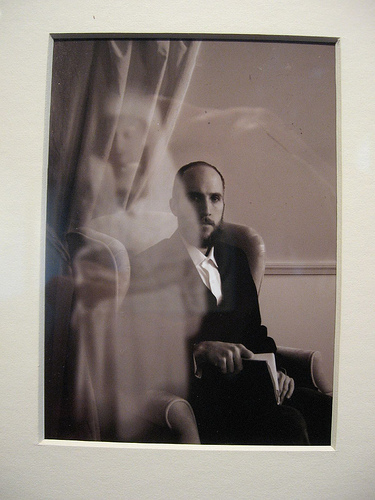

Methaphysical Forgeries: The Medium MDP with a Spirit Identified as Katie King, inkjet print

L.How do the photos fit in?

M. The Daguerrotype was invented in 1839. Spiritualism starts in 1852. That was the year that Kate and Margaret Fox start communicating with spirits in upstate New York, in Hydesville. It kind of starts as almost a goof on their parents by almost preteen girls, very young, able to convince their parents that they are communicating with spirits and particularly this ghost of a peddler killed in their home before they lived there. It snowballs into an international movement.

Pretty soon, all these new processes developed and photographs became easier to produce. I think first spirit images ones come about 1870s. The spiritualists used double exposure or layered images. People thought the process had some sensitivity to beyond what you can see. (Professional photographers were debunkers.)

Even though the whole movement comes about as a reaction to science, it also embraces science to validate itself.

There’s something inherent in photographs that is surreal. All photos are photos of ghosts–a memento mori, surreal and magical. The spirit photos get at the essential qualities of photographs in general.

Metaphysical Forgeries: The Medium Producing a Pseudopod of Ectoplasm, inkjet print

This is the first time I used myself appearing in the work. it just seemed to make sense because then you can start thinking of the idea of the artist as the medium, and start to think about the performative quality of the artwork and the stage qualities of the original spirit photographs and the Beuysian idea of artist as shaman. It’s all kind of questionable.

I see the stuff I make as a situation, where it allows you to think about things in a certain way. They’re fakes of fakes. There’s no question that I’m trying to present anything as truth or trying to buttress some kind of faith. They turn you back to thinking about the social situation that made those [older] images.

L. Are the images digital?

M. I used a digital camera, Photoshop, and printed with an inkjet printer. …They all are perfect means to talk about spiritualism’s paradoxical relationship to science and technology. There’s a grinding of gears between irrational and faith thinking and scientific method and truth, a difficult relationship–like the people trying in Pennsylvania to push back the teaching of evolution. It’s a weirdly anti-scientific movement coming out of Christian fundamentalism.

Still Live, mixed media and audio recording, made with sounds produced by this model skull.

L. Can you talk a little about the sound piece? What were the sounds?

M. All the sounds were produced just by using that model skull (a cast resin anatomical model from an anatomical supply company) as an instrument. I had help from two friends–Ahmed Salvador and Jeremiah Misfeldt.

L. How about the video?

M. I was taking the magic lantern idea and giving it a playful tweak. I liked the … imagery of eyes as this dark aperture that things project into and out of…and the eyes compared to window openings in abandoned buildings. Is seeing believing?

L. So are you mocking the spiritualists?

M. My attitude is not mockery. All of this kind of stuff comes from this very primal human place. It comes out of grief and mystification and uncertainty. People want know what is beyond this world.

Second Sight, mixed media and video; the video is projected out of the eye sockets of the skull and onto a screen.

I was inspired by the historical photos. So many of them are clearly fraudulent, but at the same time they are really disturbing. It’s still really weird. you wonder about the social situation that led to this image.

Every time there’s a new technological advance, there’s a subset of people who try to use its sensitivity to capture information from this other world or plane of existence, whatever you want to call it. The exhibit is about this situation of belief versus scientific proof, this wrestling, this tug of war, between the desire for truth and belief.