Historian and art historian Simon Schama spoke at ICA last Friday.

The house was packed Friday night for Simon Schama‘s talk, The Beast in Art, at ICA. Steve and I sat in the front, eager to hear an author we’ve long admired for books like The Embarrassment of Riches and Citizens, as well as his pieces in the New Yorker. Schama, London-born and Cambridge-educated historian and art historian now teaching at Columbia, is so popular and so busy, that Claudia Gould, introducing him, said “We booked this two years ago and we’re so delighted to have him here.”

The talk revolved variously around themes of animals in art, from Rembrandt to Ford Maddox Brown to Damien Hirst. The author apologized to any vegetarians in the audience and said there might be more in the house after his talk.

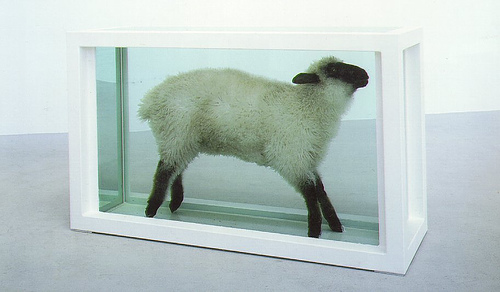

Schama began by defining art as something “to shake us into revelation … in which we apprehend the world differently.” The talk then went to Damien Hirst’s lamb in formaldyhyde, Separated from the Flock and went back in time to Rembrandt’s depictions of flayed carcas of beef, and to the Pre-Raphaelites and their symbol-laden works with sheep as stand-ins for Britain, and to Goya’s Disasters of War and to George Stubbs, the premier animal portraitist who, and here is the vegetarian/animal lover alert:

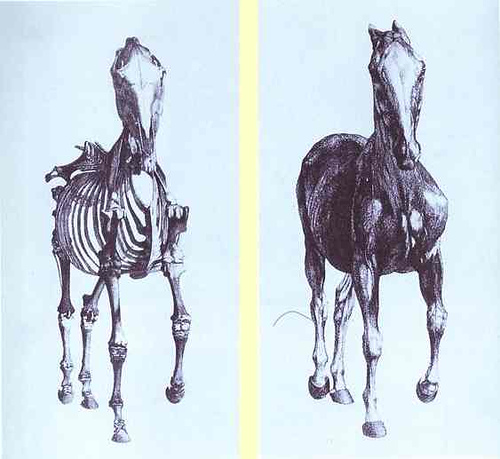

George Stubbs. Engravings from The Anatomy of the Horse. 1766.

Stubbs made his mark (and his reputation) with his anatomical atlas, a book of drawings of horses. His working method, and I think I heard this right, was to hang the horse up, bleed it to death and then flay it…”to make the perfect horse nudes,” which is what he called the stunning studly portraits of the animals that Stubbs is known for.

Whistlejacket, about 1762 by STUBBS, George, 1724 – 1806. A horse “nude.”

As the list of connections built up going back and forth in time it kept swinging back to Damien Hirst, who once, in a court case called himself a “conventional artist,” to much laughter by those in the room. Sharks and lambs in formeldyhyde? Conventional?

Damien Hirst

Away from the Flock

1994

Steel, glass, lamb, formaldehyde solution

96 x 149 x 51 cm

Charles Saatchi

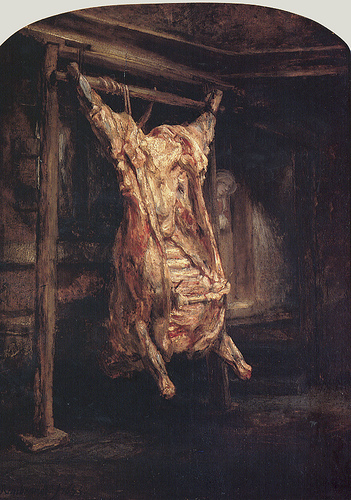

Schama talked about meat in art and dead meat and animals as symbols. And, summing up, he said: “Goya told it: “What are we? We are butchers and we are chopped meat.”

Rembrandt

Still Life with Peacocks

c. 1639

144 x 134.8 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Rembrandt

Carcass of Beef

1657

oil on canvas

94 x 67 cm.

Louvre, Paris

The Pre-Raphaelites were no slouches in symbolic animal paintings. Ford Maddox Brown and William Holman Hunt both made works in which the people of England were portrayed as either a lost flock of sheep going off a cliff, or scorned and scapegoated and in the wilderness.

William Holman Hunt (1827 – 1910) Our English Coasts (‘Strayed Sheep’), 1852. © Tate London, 2004. Presented

by the National Art Collections Fund 1946

Ford Maddox Brown (1821-1893)

Pretty Baa-Lambs

The Scapegoat, by William Holman Hunt 1854

And, while while it seemed a bit random, he showed a slide of Caravaggio’s Beheading of St. John and called it the Greatest Painting of the 17th Century.

Maurizio Cattelan The Ballad of Trotsky 1996

taxidermied horse, leather saddlery, rope, pulley, variable measurements

Caravaggio

Beheading of St John the Baptist

c. 1634

Oil on canvas, 184 x 258 cm

Museo del Prado, Madrid

He has admiration for Jenny Saville whose works have that Rembrandtian/Goya-eque flavor. And while he likes Maurizio Cattelan’s suicidal squirrel piece, he called the artist to task for his taxidermied horse, Trotsky, saying taxidermy is conventional in art.

By the end, Schama made the case that Hirst is indeed was in the mainstream of art history and that his conventions are conventional.

More than that, Schama seemed to say that Hirst’s art does not live up to the definition of art as revelatory, some little earthquake of insight into the world. All the horror, all the dead animals, maggots and more? “We get it,” he said, “Tell us something more!”

The author then thanked us for being his guinea pigs. He’s at the beginning of a new project, a new book on the beast in art, and apparently he’s test-running material with audiences (academics frequently test drive book material on their students).

Schama made a series for the BBC a while back, The Power of Art. And PBS just announced it will air the 8 episodes beginning Monday, June 18, according to the graduate student who gave the introduction to the talk.

Steve, trained as a philosopher and scientist, said of the talk — in disappointment — “It was a just a list–that’s what art criticism seems to be is a list,” meaning a string of connections without some bigger point.

While the talk was a big list of connected images, the thought was big: that contemporary art, even the Sensational art by Damien Hirst, is more conventional than we think, and that it tells us nothing new, so mostly, it is a disappointment.