William Kentridge (left) and Michael Taylor at the PMA

South African Artist William Kentridge talked about irrational power and truth without justice, in a conversation with modern art Curator Michael Taylor last night at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Those were the issues that engaged Kentridge in thinking about and responding to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission–the 1996-1998 public confession (without consequences for the guilty) of the horrors of apartheid.

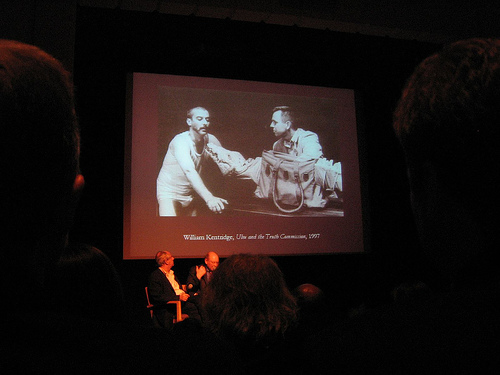

Kentridge also presented two video-ed excerpts from his play Ubu and the Truth Commission plus a drawn film also featuring an Ubu character.

Both pieces took my breath away.

Kentridge was introduced by PMA head Anne d’Harnoncourt as “one of the great draughtsmen of all times.” She said the PMA recently bought a large tapestry of his that will show in the upcoming December iteration of Carlos Basualdo’s Notations series.

From the video excerpt from the play Ubu and the Truth Commission. The puppet is a paper shredded. Ubu puts paper in and out in comes in the back. Kentridge compared this to how the government was destroying evidence and photo-stating it all at once.

The rationale for the discussion–entitled Alfred Jarry/Ubu and the Truth Commission: William Kentridge in Conversation with Michael Taylor–was that painter Thomas Chimes, now featured at the PMA, also was inspired by Ubu and Jarry. Kentridge said Ubu represented absurd power and “rapacious greed”–a perfect metaphor for what was going on in South Africa during the end of apartheid.

Kentridge said he was fascinated by Dada and the absurdism and nonesense of performances made in Zurich. And the extraordinary testimony before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission–first from the victims and next from the perpetrators–was an important part of daily life in South Africa, aired on television. “How does one deal with that documentary evidence and how does it work in a fictional form?” Kentridge asked. Ubu and the Truth Commission mixes actual transcripted evidence with clown-like action and puppetry. Kentridge said he liked the Jarry idea of using irrationality to arrive at the truth.

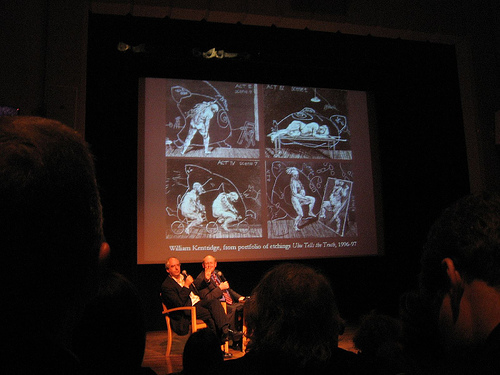

“Ubu was blind to his effects on others,” Kentridge said. The police, in fact, videotaped and photographed their own incriminated behavior–at once hiding things and being proud of them. In his video Kentridge draws Ubu as a camera on a tripod sometimes cloaked to look like Ubu, with a pointed head and a spiral.

Kentridge’s ubu-related work also includes a portfolio of etchings, Ubu Tells the Truth, from 1996-7.

Right now, Kentridge is interested in Nikolai Gogol’s The Nose, which he said in a way “carries along the same ideas.” He admired Gogol’s “schematic reduction [of a person] to just a nose,” parallel to Ubu’s reduction to a spiral and a pointed head. “I’m interested in Jarry’s method of the complete seriousness of play.”

After the talk, Kentridge took questions. Tyler student Dustin Metz asked about the place of political art, and Kentridge answered that the problem with most political art is it doesn’t leave space for uncertainty and doubt, it prescribes the answers. He gave an example of a successful piece of political art, Joseph Beuys’ Honey Pump, because it is metaphoric, and therefore more open to interpretation than Beuys realized.