Only a Scrooge could turn his nose up William H. Johnson’s art works, opening tomorrow at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The exhibit of William H. Johnson’s World on Paper is a traveling exhibit organized by the Smithsonian. But it has been enhanced by a bunch of local contributions–accounting for the number of oils in the exhibit–from area collectors and the PMA. The exhibit is a crowd pleaser.

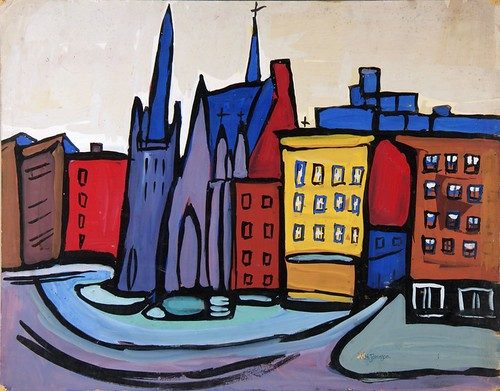

Johnson, an African-American artist born in 1901, slides down easy, with his flat pictorial charm and vivid colors, with his bold sense of graphic design, with his underlying knowledge of art history, and with his depiction of daily life in New York and in the rural South where he grew up until he moved to New York for art school in 1918.

Jitterbugs (V), c. 1941-1942, William H. Johnson (1901-1970). Color silkscreen print. Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of Mrs. Douglas E. Younger.

Johnson is one of those artists who, after learning all that art school and Europe had to teach him, figured out a way to not get weighed down by academic fussiness and foreign taste. Instead, he returned to New York and began producing pre-Pop images that reflect his African-American roots at the same time that they carry the boogie-woogie rhythms of mid-20th century New York.

Curator John Ittmann talking about the five Jitterbugs pieces by William H. Johnson, on view at the PMA, starting tomorrow, Sat., May 19. Ittman is curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs

If I’m comparing him to other African-American artists, I’d have to choose Horace Pippin for that sense of design and the use of repetitive shapes. Johnson was working at the same time as Mondrian and Stuart Davis, and the same influences clearly are there in the jazzy rhythms, the flat spaces, the geometry and the vivid use of color. Johnson also has absorbed folk art, not only from his childhood, but also from the countries to which he traveled in Europe and North Africa.

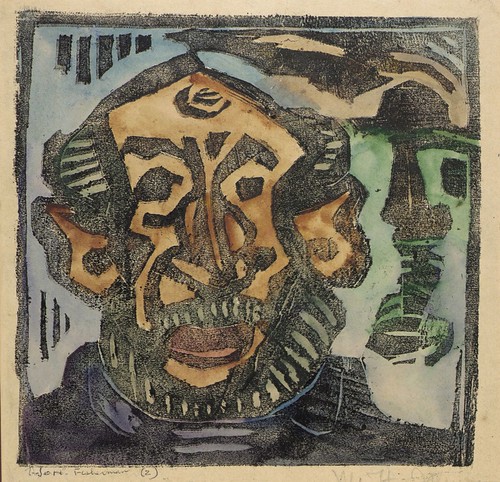

Jon Fisherman II, c. 1930-1938, William H. Johnson (1901-1970). Hand-colored block print. Smithsonian American Art Museum; Gift of the Harmon Foundation.

While Johnson’s earlier work is influenced by German Expressionism and Impressionism, after his return from Europe to New York in 1938, his work becomes something else entirely. He moves to the graphic flatness of silkscreen as well as watercolor, pen and ink and pencil, moving easily back and forth among those mediums; the resulting work has a feel of collage, quilting and applique. The African-American quilting influence also seems to be reflected in the willful anti-rectilinearity.

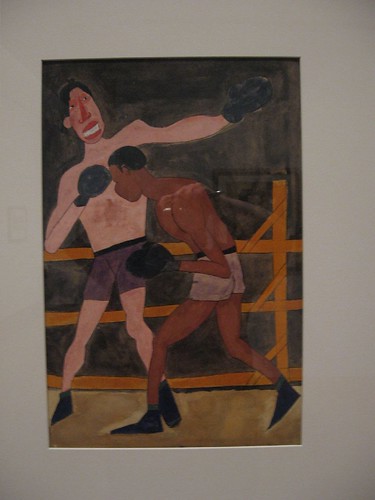

What’s stunning is the few short years, from 1939 to 1945, in which he was able to produce work in this mature style–colorful, geometric, using the rhythm of repeating shapes. It’s deceptively childlike. And wow, is it beautiful! The work from that period is mostly narrative. It’s lively even when the subject matter is dark, as when he depicts a young soldier leaving his family farm for World War II, or when he depicts injured soldiers.

William H. Johnson, Going to Church, c. 1941, silkscreen

Johnson was creating a narrative of quotidian African-American lives at the mid-century. Like Pippin and Jacob Lawrence, he created a John Brown image–it’s included in the exhibit. And there’s a sense of his boyhood Southern farm roots and his own move north, which paralells the African-American migration north of the previous generation. Lawrence’s Great Migration series was created in the same period as Johnson’s lively works on paper. But Johnson’s work is without the heroic political overlay. There’s the war and how it affected people. There’s the jitterbug dance craze. There’s a strong sense of family and the urban scene. It’s all put in personal terms.

The 1944 death of Johnson’s wife Holcha Krake (a Danish fiber-artist he met in France in 1929), had a severe effect on him, and by 1947, syphilis had destroyed his sanity altogether.

I left the exhibit of more than 80 works, wanting still more. Fortunately, I took home a catalog, Homecoming: The Art and Life of William H. Johnson, by Richard J. Powell with an introduction by Martin Puryear. The book, which has a bunch of pictures of him as well as many images not in the exhibit, made me fall in love with the guy. He was handsome, sexy and intense, and if he were alive today he would probably be one of those celebrity artists who are as much public personae as they are artists (which is not to denigrate his art, which I personally love all the more for its folk art influences).

Joe Lewis and an Unidentified Boxer, c 1939-42, tempera, pen and ink on paper

During his life, Johnson was recognized with numerous awards and a scholarship as an art student; he received financial and/or personal support from his teachers, one of whom helped send him to Europe; he worked as a W.P.A. artist; and he exhibited frequently both in Europe and the U.S. But during his final years, his works mostly remained in storage, so this exhibit, which had its first showing in 2006 in Washington, D.C., is a posthumous comeback. Give the man his due. Check it out.