Post by Andrea Kirsh

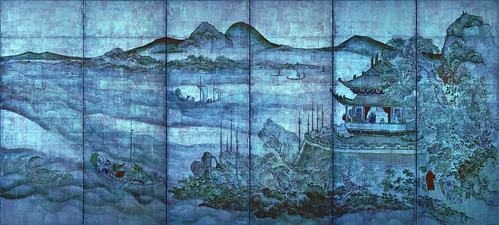

Landscape with Pavilions, Ike Taiga (1723-1776). Ink and color on paper covered with gold leaf, half of a pair of six fold screens, 66 1/16 x 146 13/16 inches, each screen. Tokyo National Museum. National Treasure.

The exhibition which just opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, “Ike Taiga and Tokuyama Gyokuran: Japanese Masters of the Brush” is devoted to two painters, a husband and wife, of the 18th century Japanese Nanga School, centered in Kyoto. Much of the work is derived from prototypes in Chinese literati painting, and it is relatively unknown in the U.S. The exhibition is spectacular and the installation particularly beautiful; you enter beneath a fabric banner to a room painted in soft blue-green, and know you are in a different world.

But the curator did as curators are wont to do: she borrowed all that she could (209 works! Only half are on view now; because of their light-sensitivity, the entire exhibition will be re-hung after June 11). Unless you’re a student of Japanese (or perhaps Chinese) ink painting and calligraphy, you are likely to find it overwhelming. Don’t let it discourage you; what I suggest for the first visit is to look at only one wall in each room; if you have energy left at the end, start again with a different wall. Or return on another occasion.

Landscapes in the Four Seasons: Evening Scene at Yueyang Pavilion, 1769, Ike Taiga (1723-1776). Ink and color on paper, hanging scroll, 52 ¼ x 22 ½ inches. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. The Arthur and Margaret Glasgow Fund. 69.48. Photo: Katherine Wetzel © Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

There will be great rewards if you’ll slow down and give the work enough attention. Taiga was a child prodigy (the earliest work at the PMA was done when he was eleven). Most remarkable is the fact that he didn’t actually know the Chinese paintings that he emulated; what he had were books that illustrated them with wood-block prints. This put him in more or less the position of many European painters during the 1950s who only knew Abstract Expressionism via the small, black and white illustrations in the art magazines. What Taiga managed to get out of those poor approximations is truly astonishing.

Bamboo on a Windy Day, Tokuyama Gyokuran (1727-1784). Ink on paper, fan, framed, 7×15 ¾ inches. Collection of Betsy and Robert Feinberg.

Both husband and wife were masters of ink painting and each had different strengths. Gyokuran was a mistress of the serpentine line and a deft designer, highly sensitive to the blank areas of paper around her painted subjects. She particularly excelled in fans.

Taiga was a master of bold forms and large compositions; his brushwork is so varied, one could think it a group show. Not only does he move from the finest of brushes to the boldest; he experimented with ink application, in some cases using a wax resist (a technique he borrowed from textile dying). His brushwork varies from grand sweeps to a method of stippled patterns that resembles European pointillism. And even these works vary greatly as to the size of the repeated strokes, some being the size of a pin-head, others approximating the finer brush-work of Van Gogh.

Bamboo and Calligraphy, Ike Taiga (1723-1776). Ink on paper, five hanging scrolls, 54 ¼ x 11 inches each work. Collection of H. Christopher Luce.

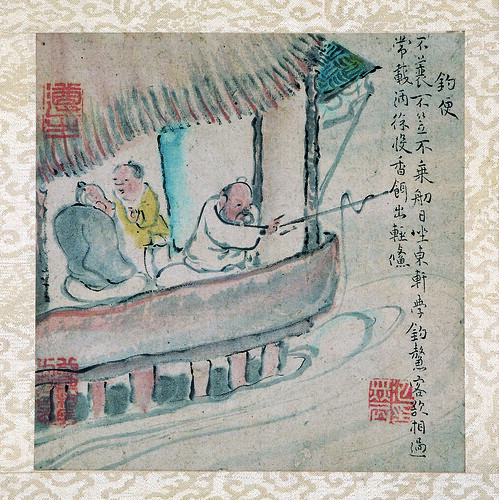

In fact, Taiga didn’t always use a brush. The exhibition opens with a group of works he painted in a technique, borrowed from the Chinese, of “finger painting”; not with the pads of the fingers, but with ink under his nails and on the finger tips. I suspect this involved the same sort of display of virtuosic showing-off that one sees in Goltzius (see his “Without Ceres and Bacchus, Venus would Freeze” in gallery 264; not finger-painting, rather a painting resembling an ink drawing). And what Taiga could do with his fingers! My favorite work in the exhibition is a finger-painted landscape (lent by the Met), that has a water-y freedom about the use of ink that reminds me of the equally-experimental ink drawings of Victor Hugo, who also occasionally used his fingers.

One of Ten Conveniences, c. 1771, Ike Taiga (1723-1776). Ink and color on paper, album, 7 x 7 inches, each leaf. Kawabata Foundation. National Treasure.

The exhibited works range from fan paintings, hanging scrolls and handscrolls, to illustrated books and a number of screens; the Japanese have designated several of them “important cultural property,” including a pair of screens on gilded backgrounds. The exhibition is a major scholarly achievement, and includes English translations (the first) of the many poems illustrated and occasionally written by both artists, and a weighty catalogue with contributions by multiple authors.

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her newest Philadelphia Introductions and other commentary at InLiquid.