Post by Andrea Kirsh

Paul Cézanne (French, 1839 – 1906), The Large Bathers, 1906. Oil on canvas, 82 7/8 x 98 3/4 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Purchased with the W. P. Wilstach Fund, 1937

Pierre Rosenberg, long at the Louvre, ultimately as President-Director from 1994-2001, is perhaps the best-known and most widely-traveled curator of European paintings in the world. I remember seeing him at a professional conference, then sighting him, always with a characteristic red scarf around his neck, in various museums around the globe. He’s written a book that might have been sponsored by the U.S. Department of Tourism, but the U. S. has no such department and the idea was clearly Rosenberg’s own.

Only in America; One hundred paintings in American museums unmatched in European collections (Milan: Skira, 2006, ISBN 13:978-88-7624-662-3) features 98 paintings and two pastels, each by a different European artist who worked from the 15th Century through 1912; as he says, dead artists. Rosenberg selected paintings that represent a major achievement or a phase of the artist’s work that could not be known from European examples of his work (all the artists being male, unless one wants to speculate that an anonymous painting was done by a woman). He provides a brief text for each, often justifying his choice, mentioning the obvious contenders and placing the work in the artist’s oeuvre. An appendix lists provenance and references for each work. The book is handsomely-produced, and if the full-color plates vary as to quality, it is likely because different museums provided variable quality transparencies.

Some selections will be no surprise, as they are the artist’s magnum opus (Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels in 1889 at the Getty or Gauguin’s Where do we Come from?… at the MFA, Boston), or mark a turning-point in his career (Matisse’s Joy of Life at the Barnes or Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon at MoMA), but others reflect different criteria. Whether intended or not, they serve to remind us that major work can be found in far-flung cities such as Oberlin, Ohio (Terbrugghen’s Saint Sebastian Tended by Irene and a Companion from the Allen Memorial Art Museum, featured on the dust-jacket), Tulsa, Oklahoma, Manchester, New Hampshire and Ponce, Puerto Rico. I‘ve yet to visit three of those cities.

Ultimately, as Rosenberg justified one of his choices: Well, the author took a fancy to it. And his fancies are neither expected nor orthodox. Several of the paintings are of unknown or uncertain attribution, and from periods late enough that we would expect to know the painter’s name. Several others are either unfinished or fragmentary. One of the fragments, Vittorio Carpaccio’s charming Hunting on the Lagoon at the Getty was identified by Yvonne Szafran, in a wonderful piece of research that used infrared examination of the panel. She found that the painting was the upper half of a panel of two women, probably courtesans, at the Museo Correr, Venice. The aquatic hunting scene was actually the background beyond the women’s balcony. With another fragment, one wing of an altarpiece by Crivelli, Rosenberg makes what he acknowledges to be a heretical suggestion: that this particular wing (St. George and the Dragon at the Gardner Museum, Boston) is more impressive detached from its intended context.

Still other selections may surprise because they are by very-little known or minor artists: Lodewijk Susi, Gaspare Traversi, Walter Goodman. And others because they are so far from what we expect of the artist; who would have anticipated a Gericault discretely-titled The Lovers (at the Getty), a rather explicit bedroom scene of a menage a trois?

Vincent Willem van Gogh (Dutch, 1853 – 1890), Rain, 1889. Oil on canvas, 28 7/8 x 36 3/8 inches. Philadelphia Museum of Art, The Henry P. McIlhenny Collection in memory of Frances P. McIlhenny, 1986

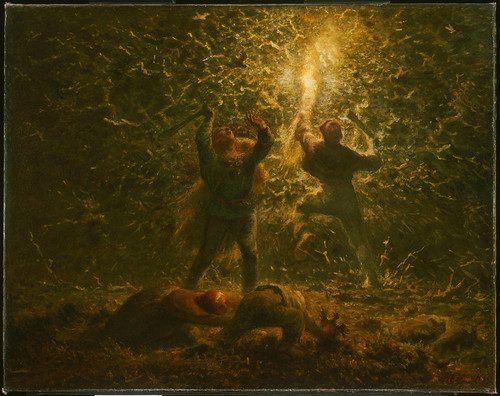

Philadelphia readers will be pleased that six of Rosenberg’s choices are from local collections: the Barnes’ Matisse (no surprise), and five from the PMA: Goltzius’s Without Bacchus and Ceres, Venus Would Freeze, Van Gogh’s Rain (a personal favorite of mine; who else ever attempted such a subject and succeeded?), Cezanne’s Large Bathers, Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, and the less-obvious Rape of Europa by Coypel and Millet’s dramatic and gruesome Bird Nesters. I was also delighted at the inclusion of Van Dyck’s Rinaldo and Armida, which I mentioned in recounting a recent visit to Baltimore (post here).

I can argue with many of Rosenberg’s choices: why Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase rather than what I consider the more important, and certainly un-matched Bride Stripped Bare…? Was a curator steeped in the 17th and 18th Centuries unwilling to see Bride as a painting? Europeans painted on glass, albeit mostly vernacular paintings, but also by Kandinsky and others. The volume might well form the basis of a parlor game for art lovers: players could make up their own lists, or make lists using different criteria. But that is precisely the fun of this book. Who wouldn’t relish a personal tour of American museums with such an enthusiastic, sophisticated and knowledgeable, yet idiosyncratic Frenchman as a guide?

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her newest Philadelphia Introductions and other commentary at InLiquid.