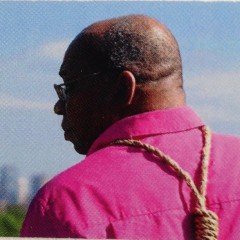

Odili Donald Odita in a beautiful bright pink shirt

Never trust what an artist says about their own work. Well, trust them only some of the time.

I’m referring to this year’s Venice Biennale American pick Odili Donald Odita. He gave a talk Wednesday at University of the Arts, part of the Food for Thought lecture series organized by the Summer MFA program. The talk was great, and the talk was puzzling.

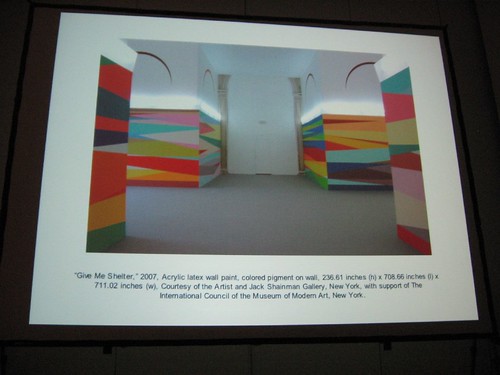

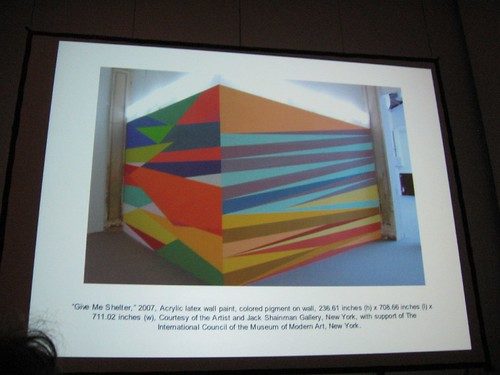

Give Me Shelter, 2007, at the Venice Biennale; acrylic latex wall paint and colored pigment on wall.

Odita, who was born in Nigeria, grew up in middle-class-suburban Ohio. His house was “a Nigerian bubble of culture,” he said. His father was an art historian and he grew up with African art and with Michelangelo. The contrasts made him confront issues of cultural dissonance and race.

It is out of this perspective that his artwork evolves.

Yet Odita does not want to be labeled as a black artist. Yet his blackness–and his Africanness–is central to what he is doing, what he is thinking about.

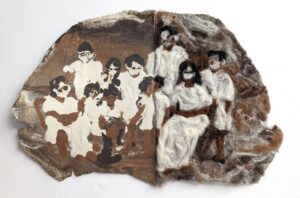

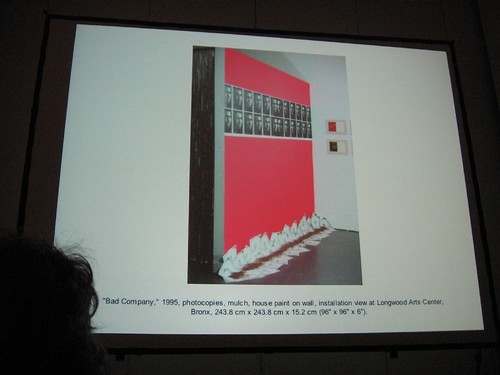

Bad Company, 1995, photocopies etc. (see photo caption).

In the course of his career, Odita has made paintings and mixed media installations. For a while he gave up painting–when he hit a wall, and felt that paintings could not express the issues he wanted to confront about the culture–identity and the exploitation of the black body in popular culture.

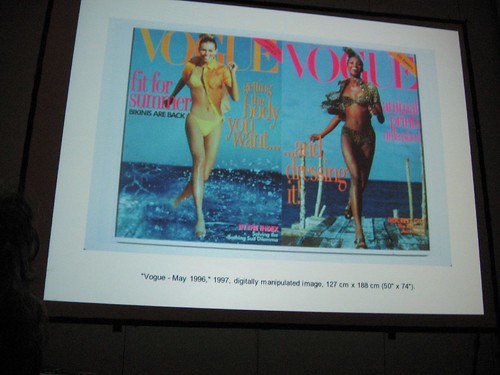

Vogue–May 1996, 1997, digitally manipulated image, in which Odita removed some of the words to emphasize what he took as the encoded message of the Vogue cover.

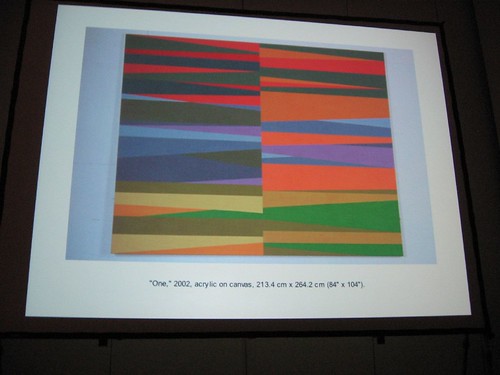

But eventually he came back to painting, and the more recent ones are direct descendants of the earlier work. They are bigger and said Odita, they reflect a different understanding of what he was doing. All the other work–the mixed media, the video–inheres in the painting. Painting is an intellectual pursuit, he said.

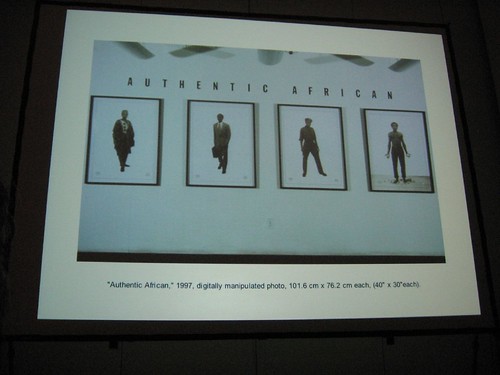

Authentic African, 1997, digitally manipulated photo, in which Odita poses himself in several outfits to protest the assumptions others have when they look at him

“Painting has to find its reason to exist, as opposed to its great history that gives it its importance,” he said. And so he looked for a way to merge European, American and African art.

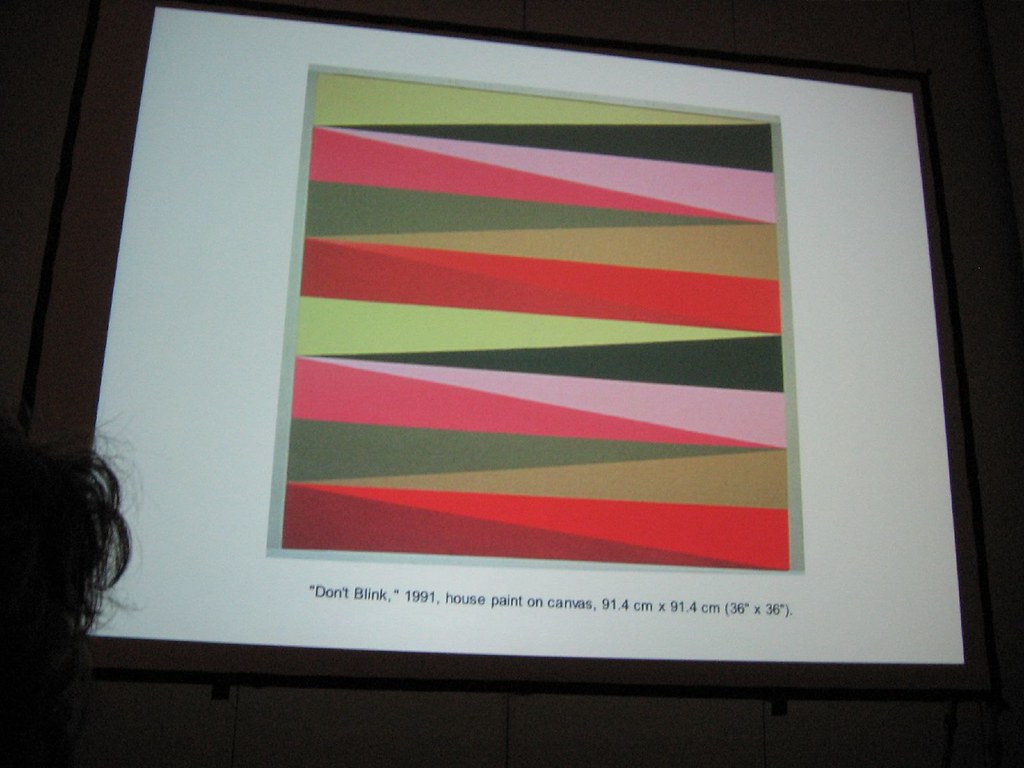

Don’t Blink, 1991, house paint on canvas

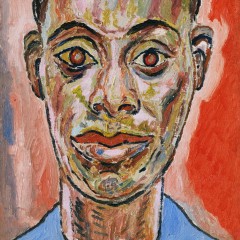

In his earlier work, before he took a break from painting, he was using areas of color to express different realities in one space, parallel to his growing-up experience.

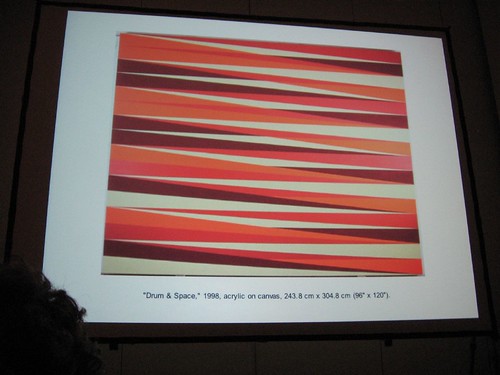

Drum & Space, 1998, acrylic on canvas

In later paintings, he talked about how the experience of a painting has to be bigger than just ideas. He acknowledged a TV-screen influence in the work, that I thought was pretty funny–and accurate. And he talked about “feeling myself in the space of the painting–at some of the time looking at something and at some of the time looking into something.”

He still uses the color strips, which he calls zips, a la Barnett Newman, and, Odita’s zips, like Newman’s, are openings into space beyond the paint surface. Odita talked about the zips as voices, vision lines, seeing something expanding, and said this reflects the influence of comics in his work (he said he loved them while he was growing up in Middle America).

But unlike Newman’s, Odita’s zips of color move back and forward, their role in the painting controlled by the eye and the mind looking. Change which color you think of as the background, a voila, you’ve got a different painting.

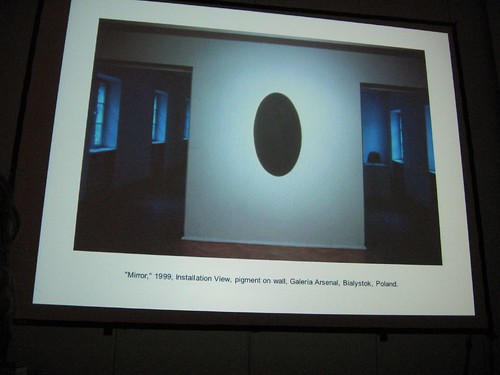

Mirror, 1999, installation view, pigment on wall

In talking about his installation, Mirror, an oval of black pigment directly on a wall, he talked about the oval as both skin and space–“maybe a reflection of myself,” he said. The illusion of depth created by the pure pigment reminded me of some Anish Kapoor works Roberta and I had seen in New York many years ago, large rocks on which a shape of pure pigment also suggested depth as well as color. Both artists’ work invite meditation.

Putting the pigment directly on the wall became a repeated strategy for him. He asked hiself the question, Why not painting? and returned to it during at artists residency in New York in 1988. “A painting has to find its reason to exist as popposed to its great history that gives it its importance.” For Odita that meant merging all the traditions, all the cultures, that were part of him and his experience–European, American and African. “The experience of painting has to be bigger than just ideas.”

Not Odita’s context?

In his first one-man show, he did not want to be placed in the context of Kenneth Noland or Frank Stella. He wondered, if a painting is a sublime space, what is the sublime in relation to a black body?

He talked about his paintings as being within an edge, but that within the paintings there were edges between the colors that represented coexistence of different worlds. Of the outer edge he said, you also have to see what’s outside the center. “The world is bigger than what we understand.”

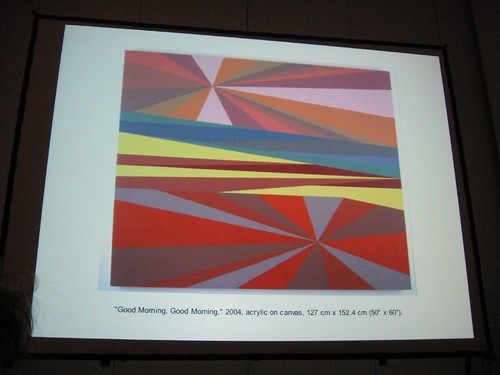

A rather landscape-like Good Morning, Good Morning, 2004, acrylic on canvas

His work became “landscapier” and then some of them more figurative. For each of them, he makes new paint. “I am interested in the color of a space, and I am interested in non-specific color,” he said, referring to colors that don’t have names.

In his painting The Elements, he said the painting had dirty colors to reflect the dust in Africa and how it affects colors. He remarked on the colors of people’s clothes and how clean they were, as opposed to the dusty colors all around them. To put this another way, Odita’s passion is color.

“I’m interested in chromophobia in Western culture,” he said. There’s an assumption that colors are foolish, clown-like, and non-intellectual. I cringed in my basic black and white outfit.

Robert Storr invited Odita to the Venice Biennale after seeing his wall piece, “Indegadadavida” in New York. Odita said using the wall addresses the very beginnings of Western painting–Lescaux, frescoes, and African painting to adorn walls. “Wall painting engages the view back into the painting, forces people to stop and engage.” It is a way to paint “in a world of intense spectacle.”

He talked about the destabilized grids in his paintings, and how the spaces within are distinct and melt into each other. “It’s about how we come to terms with our realities,” he said of his art.

He said he didn’t want to represent Western culture’s view of him–didn’t want to be seen as a black artist. Yet that’s what he paints about. He has thrown down a gauntlet, suggesting in paint that the two ideas can contradict each other, yet both be true.

Upcoming Food for Thought talks are Layla Ali, Aug. 1, at 3 p.m., and Phoebe Washburn Aug. 6 at noon.