Post by Andrea Kirsh

Cafe Serra, photo by friend of artblog Doug Witmer a.k.a. the king of the Green Line Cafe (well, he shares the title), appreciates the juxtaposition of people’s needs for art and for refreshments

Jerry Saltz, in his review of the Richard Serra exhibition at MoMA (through Sept. 10) cites a female curator who disparaged Serra’s work as “big dick art.” Well I’m not one to dis either that portion of the male anatomy or the association of sexuality with artistic production. The idea has a long lineage: Victor Hugo famously said “Imagination is intelligence with an erection,” and I’ve always interpreted Rodin’s phallic, cloaked version of Balzac as a self-portrait of the artist whose creative fecundity springs from his sexuality. Besides, the curator’s comment was also, doubtless, a response to the artist’s public persona, and it’s the work that interests me, not the man.

Richard Serra, 1-1-1-1. 1969, Lead antimony, Four plates, each: 48 x 48″ (121.9 x 121.9 cm), pole: 7′ (2.1 m) long

Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, © 2007 Richard Serra

Photo: Jenny Okun

I saw the last Serra retrospective at MoMA; in my imagination it wasn’t so long ago, but it turns out it was in 1986, in the midst of the furor around “Tilted Arc” which was illustrated on the catalog cover. I’ve kept up with Serra’s work since, so I wasn’t expecting surprises. This is one of the greatest bodies of work of the last 50 years, even if the masculine heroic does not exhaust the spectrum of late twentieth-century art. It is also a much-analyzed oeuvre, so here I’ll discuss only a couple of topics relating to MoMA’s installation.

The earlier work is on the sixth floor, although not in strict chronological order. Still, one should start there. You enter via “Delineator,” (1974-75), a great placement, for it immediately thrusts the visitor into the visceral tension inherent to Serra’s work. When I say “enter via” I mean just that: you pass into the room and step onto a 26 x10-foot steel platform, a bit uneasy to be walking on the art (pace Carl Andre), only to look up and find an equal-size steel plate affixed to the ceiling at right angles to the one below. As certain as you are that MoMA has used strong bolts for that upper piece, it is still suspended, and one can imagine being sandwiched between steel. Two further room-size pieces follow, then a gallery of work from 1967-69 including the pendant rubber “Belts,” a large scatter piece and “Splash” pieces made of accretions of molten lead.

Richard Serra, Prop. 1968, Lead antimony, Plate: 60 x 60 x 1/8 (152.4 x 152.4 cm),pole: 8′ (2.4 m) long

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Gift of the Howard and Jean Lipman Foundation, Inc.© 2007 Richard Serra, Photo: Harry Shunk

Then to a gallery full of the prop pieces from 1969, in one of the most insensitive installations I can recall. These are some of the great sculptures of the century, but they present an enormous challenge for any museum. They consist of heavy pieces of lead poised in subtle equilibrium; they are all about stasis as suspended energy. They can’t be bolted to the walls or floor; that would undermine their conceptual integrity. And the public can’t be allowed near them; risk management won’t have it. So what did MoMA do? Put them in glass pens, where they look for all the world like animals in a pet store. Couldn’t they have taken a lead from modern zoos which cage the spectators rather than the animals? If the glass had framed the walkways rather than the sculpture, the viewers would have been hardly further from the art and the works would have been free of visual constraints. I wanted to cry.

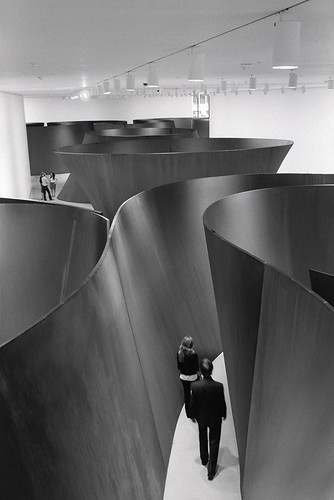

The second part of the exhibition, all new work, is on the second floor in MoMA’s massive contemporary galleries. To get to them you walk past Barnett Newman’s “Broken Obelisk” in the atrium. Serra’s work couldn’t present a clearer contrast with sculptural tradition than with Newman’s self-contained piece made of the same cor-ten steel, sitting on its vestigial base of a square plate, its upright form referencing the entire history of figurative sculpture.

Richard Serra, Sequence, 2006, Weatherproof steel, Overall: 12’9″; x 40′ 8 3/8″; x 65′ 2 3/16″; (3.9 x 12.4 x 19.9 m)

Collection the artist, © 2007 Richard Serra / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Photo: Lorenz Kienzle

“Band,” “Torqued Torus Inversion” and “Sequence” (all 2006) are massive environments of cor-ten, operatic in vision and scale, with the most luscious patinas you will ever see; the rusty hues had the changing tonalities of velvet. I found myself constantly telling visitors not to touch because the oils from their hands would mar the surfaces. Yet I understood their desire to run their hands along the works as they progressed around and through Serra’s coils and labyrinths. Serra’s work is always parsed with the body, and these pieces presented architecturally-scaled spaces no visitor had ever known, with never a right angle to compare with one’s upright posture. I thought afterwards that MoMA should have acknowledged this and given everyone white cotton gloves to wear in those galleries.

Installation view of Richard Serra Sculpture: Forty Years in the second_floor Contemporary Galleries at The Museum of Modern Art.

© 2007 Richard Serra / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, Photo: Lorenz Kienzle.

Objections and comments aside, this is an exhibition of work of ongoing challenge, excitement and importance. No one should miss it. MoMA has added extra hours to accommodate the interest (hint: I went at 10:30 am on a Sunday when the museum opened, and didn’t have to battle crowds; New Yorkers just don’t like to rise early on Sundays. Otherwise negotiating the three pieces on the second floor would resemble trying to walk in the Village while the Gay Pride parade was in progress – which was my experience later that day).

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her newest Philadelphia Introductions and other commentary at InLiquid.