Post By Daniel Payavis

Modernist painting has put serious restrictions on the illusion of pictorial space that had been growing so rich for more than 400 years. The limitations modern painting set for itself, at once cutting itself off from its potent past and viable future, led Frank Stella, in his lecture series Working Space, to rally for the essential nature of illusionistic space and its necessity for the ensured vitality of painting.

Stella’s relationship with space is complex and unclear; he advocates the use of inventive pictorial space within the painted image, yet has hardly dealt with it himself.

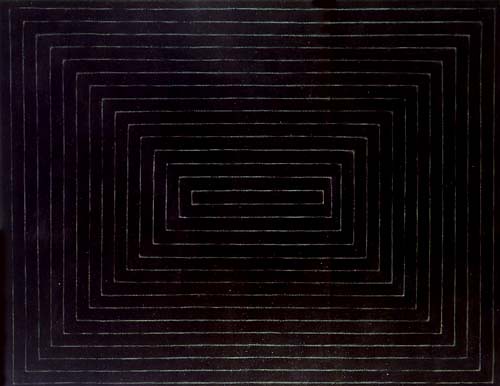

Frank Stella, fig. 1. Early black series.

While lecturing extensively about the pictorial genius of Caravaggio, Manet and Picasso, he was making three-dimensional wall relief sculptures in painted aluminum. Stella the theoretician seems entirely in favor of illusionistic space while Stella the artist seems in favor of actual, breathable space.

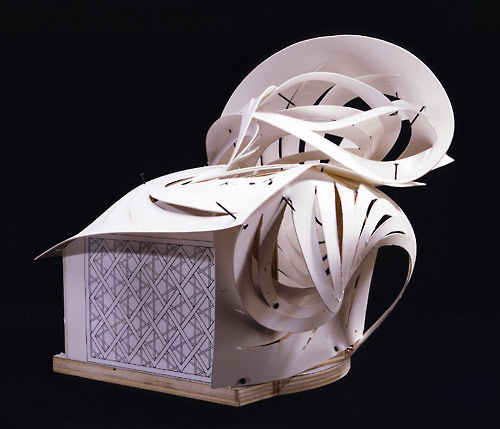

Stella’s three recent shows in New York, one at Paul Kasmin in Chelsea and two at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, reveal that his sculptural mode of thinking has only expanded over the years. Has Stella been contradicting himself the whole time, talking one way and working another? Perhaps one of the shows at the Met, Frank Stella: Painting Into Architecture, best reveals a way of seeing Stella’s presumably divergent ideas about space as complimentary.

Stella, figure 4. Architectural model, on view now at the Met.

Many of Stella’s architectural proposals (fig. 4) are on view at the Met show, including an enormous fragmentary mock-up for part of a building. Several paintings also make an appearance, and the coexistence of both bodies of work serves as a reminder that Stella’s paintings have always been more or less architectonic. His early modular black paintings (fig. 1) are composed of repeating units, painted bands, which he perfected later in his metallic series. Such a method, analogous to architectural construction, might be likened to the laying of bricks. The idea was not to develop a pictorial structure, but to cancel it out in favor of the physicality of the painting as object.

His Protractor series (fig. 2) permits overlap (and thus space), but the dominant theme of these paintings relates to medieval and early Renaissance painting: the relation of a spatial inner image to a frontal outer structure. In other words, Stella’s interest is how the image (a mural or altarpiece) controls or is controlled by its mode of containment (architecture). Stella essentially examines a struggle between pictorial and actual space, both of which are vying for the viewer’s attention.

Stella, figure 2. From the protractor series.

Stella’s most recent painting development, his three-dimensional metal pieces (fig. 3), is his homage to painting. Stella wants impossibly to make painting more than a residual element of a wall – he wants us to feel the presence of painting as perhaps was once possible (before photographic media). To do this, he must borrow from the language of sculpture to exclaim that painting is not subservient to architecture – that it is a kind of architecture in itself.

So it appears that although Stella has become more sculptural in method over the years, he has done so in the name of painting. Architectonic work has provided him a means to scrutinize the balance between illusionistic and actual space, between painting and its environment. Perhaps all of Stella’s work has been about an encouraging idea for painters: that painting is such a powerful force that its reality blends and merges with our own.

–Daniel Payavis is a 2007 graduate of University of the Arts with a BFA in painting.