Post by Andrea Kirsh

If the PMA’s original building, with its classical pediment and columns, presents itself as a temple of art, the new Perelman Building, designed so it’s flooded with natural light, speaks about access; access not only to art but to study about art. This is particularly clear in the part of the building originally inhabited by Fidelity Life Insurance. It houses four areas devoted to public learning: a teacher’s resource room, a library, and two study rooms: one for prints, drawings and photographs, the other for costumes and textiles. You don’t have to be in a PhD program or even in school to make use of the study rooms; anyone with a serious interest (artists, collectors, enthusiasts) can make an appointment to view particular works. Neither department has entirely completed the move; when the study centers are open for use, their hours and contact information will be posted on the museum website.

A view of the library reading room in the Perelman building, with bronze plaques by Paul Manship, representing the four elements. (Photo: Sahar Coston)

You don’t even need an appointment to use the library. Roberta, Libby and I talked with director, Danial Elliott, who’s delighted with the new, 12,000 sq. foot space, four times the previous facilities’. The old space could barely accommodate two researchers at a time; the new library has expansive tables (topped with cheerful chartreuse laminate), multiple computers for electronic resources and open stacks for some reference works and current periodicals (most books are in closed stacks). This is a tremendous resource for the city, making available books, museum catalogs, auction catalogs and a range of periodicals that can’t be found at the Free Library or local bookstores. Looking for “Tema Celeste,” “Fashion Theory” or “Environmental Design”? You can find them at the PMA (the library contents can be searched on-line at http://pacscl.exlibrisgroup.com:8994/F). The library also houses rare books and archival material; these range from a 15th-century edition of Boccaccio’s “Decameron” (currently on display in the library) to work from Marcel Duchamp’s estate.

Evening Dress, Winter 1962, James Galanos (American, b. 1924). Silk lace, sequins, beads, rhinestones, and crystal drops, silk jersey. Embroidered by D. Getson, Eastern Embroidery, Los Angeles. Gift of the designer, 1963

The Costume and Textile department are also ebullient about their new facilities. Kristina Haugland (the only curator I know who can legitimately hang images of shoes and brassieres in her office) showed us around the study room and adjacent textile conservation lab. We also saw the gallery for textile study material on the second floor (still mostly empty at the moment), as well as the new, 2,450 sq. foot gallery on the ground floor. That’s 10 times more exhibition space than they’ve had.

Stingray Swan Evening Dress, Spring/Summer 2001 (ready-to-wear collection), Ralph Rucci (American, b. Philadelphia c. 1957). Silk gazar, double-faced duchess silk satin, ostrich spine. Gift of the designer, 2005

The opening exhibition celebrates three designers with Philadelphia connections: James Galanos, Gus Tassell and Ralph Rucci. Elegant day and evening dresses (no pants suits here) are arranged around the periphery of a room painted an atmospheric midnight blue. A free-standing pedestal near the entrance displays a “little black dress” by each designer, as classic as ever. The overwhelming impression is an almost architectural devotion to line and construction; the spirit of Christobal Balenciaga hovers over the gallery. While several of Galanos’ gowns are covered in beads (in one case, enough to rival Las Vegas), most of the clothes are surprisingly unembellished. One of Tassell’s cream and black evening gowns approaches monastic severity; these are clothes for very confident women who want their dresses to set them off, rather than upstage them.

The most surprising gown was a Rucci evening dress inspired by Cy Twombly. The front was a floor-length panel of heavy silk, hand-embroidered with a motif taken from one of his paintings at the Tate. Anne d’Harnoncourt would carry off such a dress splendidly; perhaps Rucci can create one based on the PMA’s Twomblys.

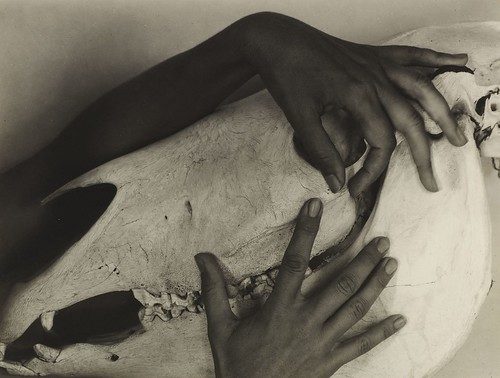

Dorothy Norman, who also had an affair with Stieglitz, contributed Stieglitz photographs to the PMA. This is one that came from her:

Dorothy Norman XXXIII, New York, 1933, Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864 – 1946). Gelatin silver print, Image: 4 3/16 x 3 5/16 inches. From the Collection of Dorothy Norman, 1997

The next gallery exhibits “Alfred Stieglitz and the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” 50 photographs from the PMA photograph collection, which was initiated with a donation from Stieglitz’s estate. The curators are obviously reveling in their new space, with high ceilings and good proportions; the exhibition looks better than anything I’ve seen either in the narrow hallway gallery on the south side of the original building or the galleries across from the gift shop. Stieglitz wears two hats in American art history: artist and impresario; and both roles enhanced the PMA’s collections. His New York gallery showed European modernism before the Armory Show, and he exhibited both European and American modernist artists decades before New York museums would argue over their relative merits. The PMA is one of several museums that benefited from his bequests of his own work and that of the artists he championed.

The exhibition gives an overview of Stieglitz’s photography, including portraits (largely of artists), urban images, the “Equivalents,” and studies of Georgia O’Keeffe. His series devoted to O’Keeffe was public love-making; the middle-aged artist caressed every bit of her beautiful and youthful body through his camera lens. The photographs here are mostly of her expressive hands, although there’s one full-length nude, complete with long-taboo pubic hair (think of those depilated , nineteenth century nudes). The most striking of the urban views are those taken from his 13th floor apartment in the Shelton Hotel, in midtown Manhattan. Stieglitz plays with shadows that one skyscraper casts upon another, and these dark, uninflected voids daringly occupy the center of the compositions.

Hands down, the most interesting for me will always be the “Equivalents,” in which Stieglitz flirts with abstraction. The title of one, “Music” (from a series of 10) shows a debt to Kandinsky’s “Klange,” which associates visual abstraction with music. If you don’t know the series of tiny images of clouds, rush down to see them. In pointing his camera upwards, Stieglitz freed himself from all vestiges of ground-line and perspectival space and allowed his imagination to float on the wind.

A Willy Shelton necklace in the gift shop (photo by Libby)

No self-respecting modern museum would be complete without a gift shop, and the best of them build upon the strengths of the collections. The shop in the Perelman concentrates on design and objects with a decidedly modernist bent. Libby and I were both attracted to the jewelry that Willy Shelton made from industrial metal shavings; it’s perfect for the woman who appreciates the re-use of scrap materials by Rauschenberg, Chamberlain or Nancy Rubins. I’d wear the necklaces or earrings in a minute, if I could afford them. I also coveted a stool designed by Frank Gehry; it’s silver surface resembles lacquer, although the shop staff said it isn’t (but couldn’t tell me what it is).

A stool designed by Frank Gehry, for $500 (photo by Libby)

For only $15, even less wealthy visitors can enjoy artist-designed jewelry: Anni Albers made kits for necklaces in response to a 1941 exhibition of common object jewelry. One employs hair-pins, another paper clips, and my favorites use industrial hardware (washers and some unidentified brass spacers). The shop also carries assorted housewares designed by Aalto, Magnussen, Brandt, Fornasetti and others, as well as some knock-offs of Joseph Albers and Mondrian that reflect a questionable taste and respect for intellectual property rights.

This should certainly expand the options for birthday and holiday shopping, and support the PMA at the same time.

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her recent Philadelphia Introductions articles at inLiquid.