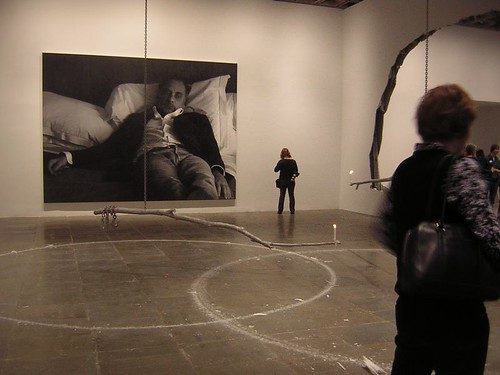

Rudolf Stingel, June 28-October 14, 2007, Whitney Museum of American Art

Photo by Sheldon C. Collins.

The room is a street-punk Versailles.

After years of knocking ourselves out on each trip we take to New York, we have finally calmed down a little. This time we didn’t walk until we dropped. And this time we didn’t try to see everything from the Bronx to the Battery to Bed-Sty.

The top attraction of going to New York was Roberta’s friend photographer Madelyn Roehrig (see post). She was visiting MoMA and the Whitney. But we decided it was the Whitney’s Rudolf Stingel exhibit that appealed the most. For all that anticipation of an interesting show, nothing prepared Roberta, Madelyn and me for the experience we had when we walked off the Whitney elevator into Stingel’s foil-coated insulation board installation–the foyer to the one-floor exhibit.

The room was illuminated by a single ballroom-scale chandelier, its light multiplied by the foil walls and ceiling. The walls, scarred by the graffiti of whoever passed through and had the urge to write, dig, draw or embed, seemed baroque and heavily patterned, although the marks were random. The walls within reach were marked by visitors to the Whitney. The upper-level panels, taken from a similar installation at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, were marked by visitors there. (Chicago MCA organized the exhibit and MCA Curator Francesco Bonami curated it).

Rudolf Stingel, June 28-October 14, 2007, Whitney Museum of American Art

Photo by Sheldon C. Collins.

The extravagance of the scarred and mirrored walls was spectacular. Both decorative and architectural, they conveyed the concept of skin and what’s under it; they represented desecration and scarification of art and the museum space, while providing the disorientation and infinity of mirrors–the total effect was razzle-dazzle for the body and the brain.

I just want to say I loved all of Stingel’s paintings, too, but it was the installations that knocked me over.

The other amazing space had a mirrored floor and on each wall, a gold painting with baroque wallpaper pattern. Once again, a conversation between skins and bodies and architecture and sumptuous decoration made us almost lose our bearings. The mirrored floor felt like a window into deep space that threatened to let us drop through. The walls and ceilings were suddenly on the floor, in the reflections. And walking on all these things felt like a desecration–like walking on art. The museum embargo on walking on Carl Andre’s minimalist metal rugs made stepping out onto the deep space mirrors all the more transgressive. It is here where the decorative and the rarified meet the body that Stingel walks his way to questioning the layered roles of art, architecture, decoration.

Untitled, Rudolf Stingel, 2000, Styrofoam , Each: 48 x 96 x 4 inches (120 x 240 x 10 cm); Overall: 96 x 96 x 4 inches (240 x 480 x 10 cm), Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Stingel, by the way, was born in Italy, and spends part of his time there and part in New York, and bringing that Italian love of baroque decoration and extravagant surfaces is an important part of Stingel’s art. On the other hand, he’s not afraid of employing the Home Depot DIY aesthetic at the same time that he’s unafraid of conceptually moving walls to floors and floors to walls.

What used to be a floor, a besmirched white rug from the artist’s studio, Stingel mounted on the wall–wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling. It looked like a painting and it even looked a little like a paint-splattered concrete wall. It also looked like what it was–a dirty rug. Of course Jackson Pollock came to mind, not just for the splatters, but for the location of the work while it was being marked. But, unlike Pollock, it was more about the change in location. Amazingly, it didn’t look like it didn’t belong where it was!

And “drawings” of footprints stomped into on white styrofoam slabs also hang on the wall but must have been an action on the floor. While we were in this room, we bumped into Pphiladelphia Museum of Art contemporary art Curator Carlos Basualdo and his wife. Basualdo expressed an interest in the repetitive motions involved in creating some of Stingel’s work.

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled, 1993, Oil and enamel on canvas, 99 ¼ x 66 1/16 inches (252.1 x 167.7 cm), Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York

Although Stingel covers a pristine white museum wall with a dirty white rug, he does not come off as merely outrageous, or even as silly. I totally bought into everything he showed here, even the older work in the show, like the scarred and pitted silver-coated paintings with the colors seeping out from underneath. They are made with a predetermined process. But honestly, they’ve got a whole lot more to say than any Jules Olitsky color field painting that I’ve ever seen. Stingel totally gets the surface, and, unlike Olitsky, he gets what’s underneath, and he relates it all to the body–his body and how he makes the work, our body and how we stand in relation to the work, and to the world we live in.

In the last Whitney Biennial, a Stingel black-and-white self-portrait, Untitled (After Sam)–i.e. after a photograph by Sam Samore–seemed almost conventional hanging next to Urs Fischer’s hole-in-the-wall and candle installations. But in the context of this show and Stingel’s own assault on the museum’s walls, the work looks really great. After this exhibit, I’m looking for Stingel to be all over the place.