Courtesy Sonnabend Gallery.

Candida Hofer

Palacio Nacional de Queluz II

2006

C-print

200 x 247 cm

CH-399

Candida Hofer’s wall-sized photos — portraits of grand architectural interiors, printed so large that the gallery-goer feels almost as if she’s in the space depicted — are both deadpan and glorious. Hofer’s love of these beautiful, historically-reverberant interiors is palpable. The way the rooms are lit, the painterly color, the stillness and drama of the shot, all this telescopes the artist’s love like a kiss. There may be blemishes in these old places but they’re sure not visible.

Courtesy Sonnabend Gallery.

Palacio Nacional de Mafra I

2006

C-print

250 x 200 cm

CH-380Notice the pink and blue.

Hofer’s photos are not glam shots meant for advertising the architecture. And if one were to speculate on what these pictures are really all about, it’s a good guess that the subject is what’s everywhere implied but never stated, human history. Humans commissioned the buildings, built them, lived and worked there, loved and died there. And that history, some of it small and intimate and some of it public and political and presumably involving power struggles and actions not so humane, inhabits these room. These are the proverbial walls that could talk.

Courtesy Sonnabend Gallery.

Teatro Nacional de Sao Carlos Lisboa I

2005

C-print

200 x 276 cm

CH389

When you stand in front of this work in Sonnabend, you feel like you’re on the stage.

There’s no way to capture history in a photograph if there aren’t people in the frame. People make the history. But all photos of buildings are in effect portraits of the building’s inhabitants at a certain level. And what Hofer does in her monumental works is offer up the space as a puzzle, something with secrets to be discovered or perhaps dreamed.

Because of the hushed atmosphere and the lack of action of any sort, the works have a slight surveillance buzz to them. They are conspiratorial — showing the spaces–many of them conceived of as private spaces but now public spaces — the way you and I will never see them, quiet and devoid of other people. The photographer’s gift here is to give you access — second-hand, like a voyeur — to the space the way she had access.

Courtesy Sonnabend Gallery.

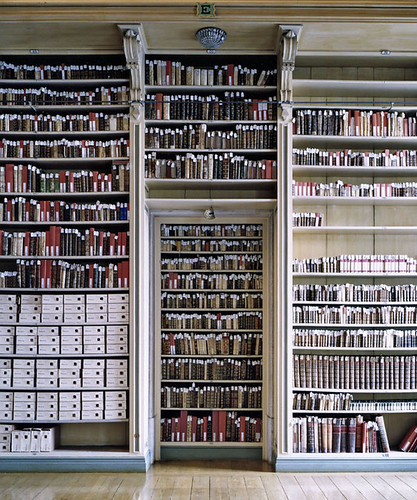

Biblioteca do Palacio Nacional da Ajuda Lisboa I

2006

C-print

170 x 152 cm

CH-391

These are slow works. Both their large scale and the level of crisp detail requires that they be absorbed not in an augenblick but with a steady studious eye. And what the leisurely perusal facilitates is the reverie about the place’s history. Mostly we don’t really know the history of these places. And in a strange way, they all start to look alike –one palace resembling another; one library or theatre bearing more than a passing resemblance to another. But it doesn’t matter. For the works’ genericity allows the viewer to tap into the universal, almost fairy-tale-like story being evoked. We all know at least one story of a king, queen, palace, castle, opera house, library. We’ve all imbibed the story (albeit fictional) on some level.

Hofer’s new body of work on display at Sonnabend Gallery (through Oct. 13) depicts palaces and libraries in Portugal. (See Libby’s post on Hofer in Philadelphia for a synopsis of how the artist came to photograph in Portugal).

I saw the Sonnabend show with Cate, a photographer, who was struck by the artist’s use of light and shadow to cause areas to flatten out as they would perhaps in a painting. Cate noticed for example that in the throne room (top image), the artist (I’m assuming the artist was in control of the lighting) had opened window shutters far away from the throne but kept them shut in the throne area. The result created moments of blinding light in the foreground and a dark vaporous mystery area in the rear. In fact, you need to look very hard past the beautiful checkerboard space to see that the room contains two seats that must be thrones….they are almost beside the point here.

While in Philadelphia, the artist said that she considered her works like a painter considers a canvas and that she took liberties with the lighting and color to enhance the aesthetic she was after. You can see this here and in the other works where the color blue (or in some cases pink) washes over the image in strange and wonderous ways.

Courtesy Sonnabend Gallery.

Biblioteca do Palacio e Convento de Mafra I

2006

C-print

200 x 247 cm

CH-361

It’s possible to read into the artist’s ouervre a critique of culture, of wealth and power. This is an artist who learned from and worked with Bernd and Hilla Becher, noted German photographers whose black and white images of coal and coke plants and other monstrous industrial edifices must be read as not mere documentation but critiques of mankind’s industrial beginnings and the use of (and overuse of) resources.

Like the Bechers, Hofer is documenting so many of the same kind of edifice that the ouervre feels forged with a missionary-like zeal. Also like the Bechers, Hofer’s works possess a manic energy: Their emphasis on detail, detail, detail is almost stupifyingly humbling. These are not photos of nostalgic reverie but images that mean to provoke. And provoke they do.

The works look wonderful in books where they can be studied at leisure. And there are many books. But the way they are seen in the gallery — power pictures of power places that ask you to put yourself into the picture — is the way they’re best seen. That’s when you’re confronted with the reality of these places — their crazy beauty and their dense histories which even if you don’t know can be imagined.

Hofer spent a week in Philadelphia this fall photographing institutions here like Eastern State Penitentiary, the Furness Library on the Penn campus and Philadelphia’s City Hall. We don’t have palaces here and our buildings don’t have the same opulence that old world edifices have. But our new world buildings have history in them, and I’m very much looking forward to how Hofer serves it up.