Post by Andrea Kirsh

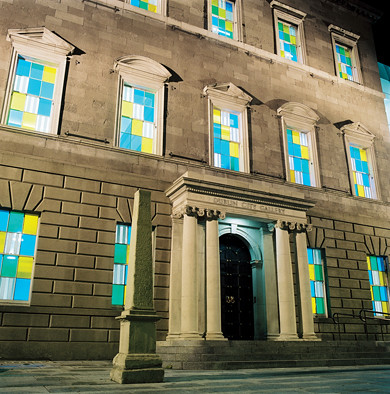

Daniel Buren, 3 Colors for a Facade in Dublin, 2006

I spent the first crisp and sunny day of autumn indoors, in a basement auditorium at the Phillips Collection for a symposium: “Issues of Content: Museums of Modern and Contemporary Art Today.” It’s the first public program of the Phillips’ new Center for the Study of Modern Art, a collaboration with the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign (the connection between the Phillips and UI being Prof. Jonathan Fineberg, a distinguished scholar and teacher who’s the Center’s director).

There was not only an illustrious panel, but an impressive audience (and a full house) that included Ned Rifkin, the Smithsonian’s Under Secretary for Art, Olga Viso, the director designate of the Walker Art Center, Alan Wallach, Prof. of Art and Art History at William and Mary (and notable critic of museum practice), as well as art professionals familiar to Philadelphians: Amy Schlegel, Director of the Galleries at Tufts University (and formerly of the Art Alliance), Roberta Tarbell, Prof. of Art History at Rutgers Camden, and Kate Butler, who’s cataloguing the Matisses at the Barnes Foundation (we sat together on the train and discussed the implications of the Barnes’ move).

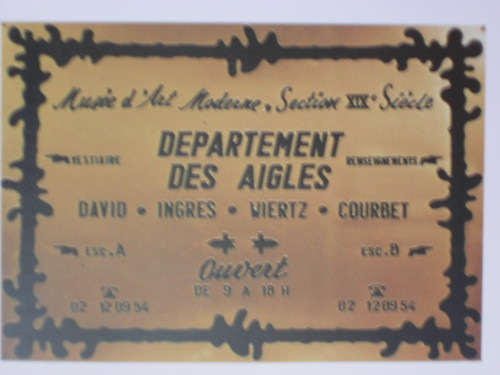

Marcel Broodthaers, Departement des Aigles, 1968

The art market as devil

The morning began with two speakers who pulled no punches in their criticism of current museum practice. The opening talk was by Benjamin Buchloh, formerly a critic, who has matured to look the part of his current position as professor of art history at Harvard.. Buchloh acknowledged his own association with artists involved in institutional critique (Broodthaers, Buren, Asher, et al.) and interrogated why their practice came about. Then, suggesting that it might just be nostalgia on his part, he said that art as criticism of the bourgeois public sphere (Habermas’ concept) and serious criticism of such art no longer mattered. The public sphere has broken down and the art object is both obsolete (in critical terms) and fetishized. Filtering his convoluted dependent clauses and politically correct rhetoric, I conclude that he blames most of the ills of the current museum situation on the spectacularly inflated art market: while museums in the past depended upon the judgment of curators, critics and historians, he said, in the present museums base their judgment entirely on the market.

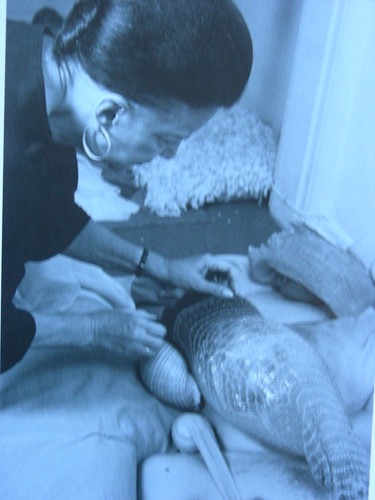

Exhibiting performances past

The next speaker was Suely Rolnik, psychoanalyst and cultural critic, who documented the process she went through in organizing an exhibition of Lygia Clark, the Brazilian artist who intentionally situated her interactive performances outside of museums. Rolnik wanted to avoid merely exhibiting physical relics and photographic documents of performances, but her primary solution seemed to be adding filmed interviews with people who either participated in Clark’s activities or lived through the period and were able to give it historical context (at least from a personal perspective). It wasn’t clear why her solution of filmed interviews needed a museum exhibit; it might have been as appropriate on television (or published in a book). But the question of how to present art that arose outside of museums has come up for many in the audience, so it was interesting to hear another perspective. At one point Rolnik implied that many curators of contemporary art feed off the work of artists in the course of their own, careerist goals. No one was visibly offended by the comment. From my own curatorial experience, the career rewards of curatorial work are too paltry to influence decision making or deflect it from the higher goals of the institution. Perhaps other curators have more to gain.

Rethinking museums, top to bottom

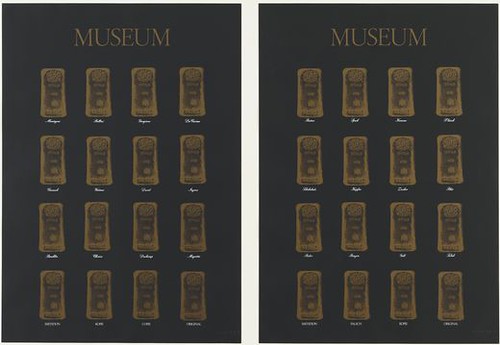

The most eye opening talk (for me, and for some of the respondents) was by Manuel J. Borja-Villel, director of the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona (MACBA), who acknowledged that his English was likely to be more difficult than his Brazilian or German predecessors (it was). He’s been rethinking the entire premise of the museum at MACBA–not only creating narratives of contemporary art beyond the canonical ones (particularly in relation to questions of nationality, or regionality in the case of Catalonia), but moving beyond the space of the museum, engaging his audiences as active participants who generate content, and questioning the museum’s emphasis on collecting only unique and valuable objects. He posited that the museum could function more as an archive: since much art is now digitized, the value of uniqueness (or of limited editions) appears entirely as a relic of the market, and museums need not be complicit in perpetuating that system (e.g. it serves no artistic or educational value for the museum to own one of three rather than one of thousands of a particular video or digital print). I like the idea, but it doesn’t quite solve the problem that artists need to eat. Perhaps in Spain artists get government support; museums certainly do.

Marcel Broodthaers, Museum-Museum, 1972, screenprint, Museum of Modern Art–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia.

Who’s the audience?

The respondents were Bruce Altshuler, Director of NYU’s Program in Museum Studies; Neal Benezra, Director of SFMoMA; Kathy Halbreich, Director of the Walker Art Center; and Lisa Phillips, Director of the New Museum, joined by the Phillips’ Gates. Most of them responded to points Buchloh had raised about mass museum audiences and what drives them; Buchloh had suggested a bifurcated audience of professionalized and well traveled art world on the one hand, and then the more casual visitors. Phillips said that based on visitor studies (which a number of the museums employed) the audience was rather more complex, indeed multiple audiences. Someone asked whether all the use of visitor studies and talk of responding to audience didn’t sound a lot like marketing (implying that making decisions in museums had become similar to the process at Proctor & Gamble). Halbreich explained that listening to their visitors didn’t mean asking them to determine which artists they exhibited, but did enable the institutions to do things like provide more useful signage and educational programs.

Money for better or worse

There was a certain amount of talk about money and how things like attendance figures determine museum programs, and Neal Benezra made a couple of comments which summarized much of their thought: firstly, that we can’t talk of “the museum,” because museums vary tremendously (as reflected in the four they headed); and secondly, that museum directors all work hard to keep their institutions free of influence from the money they need to keep going. The assembled directors were all impressive in their thoughtfulness, dedication to art and artists, and openness to new ideas and to self-criticism–realists and idealists at the same time. If I had to spend a beautiful day in a museum basement, at least I had good company.

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her recent Philadelphia Introductions articles at inLiquid.