Post by Andrea Kirsh

Edward Hopper, Night in the Park 1921

etching on paper, plate: 6 13/16 x 8 1/4 inches

National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection, 1963

I thought I knew Edward Hopper’s work. I didn’t. The work currently at the National Gallery of Art (through Jan. 21, 2008) showed me a much more interesting artist than I’d known. The exhibition, organized jointly by the NGA, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Art Institute of Chicago, isn’t revisionist; it’s a straightforward, chronological hang of 96 prints, watercolors and oils which give a representative view of Hopper’s career. The Gallery has installed it with restraint, the only additional material being a 15-minute film (a longer version is available for purchase) which looks at the artist’s life and interviews Eric Fischl and Red Grooms about Hopper’s influence. As Grooms says, “Everyone likes Hopper.” Perhaps I’m just now ready for his work.

The first room contains prints (etchings and a single drypoint) which the artist turned to in 1915 when his paintings wouldn’t sell. Twenty years ago I worked for a dealer of American prints and remember thinking that of all the American artists whose graphic work sold for thousands (at that time it was a short list), Hopper was the one whose prints were most likely to end up, unrecognized, in the bins of some dealer of second-hand books and old prints. They never did.

His prints have grown on me. They anticipate the subjects for which Hopper would be known: landscapes seen mostly in the middle distance, street-scapes, figures usually seen from the back or in profile, views through windows, and light and shadows, which were his real interest. I appreciate his technical control and beautiful printing: deep, black lines which sit on the surface of the paper and beautiful use of plate tone (slight amounts of ink left on the un-etched portions of the plate, so they print as grey instead of white). I’m not sure he ever had such technical skill with paint. And I value his restraint. Hopper already knew how to condense his subjects; he shows just enough, and no more detail than is needed.

The mature artist appears in the exhibition’s third room, with scenes of New York City at its least spectacular: unremarkable people in unremarkable settings. But we begin to see Hopper’s ability to people his works so as to suggest a narrative and create an emotional tension. Vermeer used the same effect. We sense that we are seeing a slice of a larger story and we project the rest of it onto the paintings, filling in past events or anticipating future ones.

Hopper’s narrative skill (if I can call it that) is supported by his formal skill. This is clear with the wonderful “Automat” (1927, a painting I didn’t know, but then it’s at the Des Moines Art Center). A young woman sits alone in a café; we’re told, but not shown, that it’s an automat. Her features are painted with no more detail than Hopper directed at the radiator to her right. Everything about the painting leads us beyond the picture-window at her back. A row of overhead lights is reflected in the window, creating one orthogonal from lower left to upper right. Crossing it is an opposing orthogonal created by the girl’s head, leading to the fruit on the ledge behind her and finally to a faint streetlight outside. All of this heightens the contrast between the over-lit interior and the blackness outside. We wonder why she’s on her own; she’ll have to leave in that darkness. Is she meeting someone? Has he (she?) just left? Is she escaping something unpleasant at home, so that even this bare, commercial space is a refuge? It’s up to us to fill in the blanks. Hopper gives us no clues.

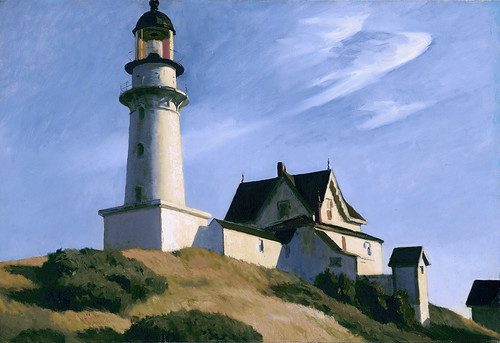

I can’t say I gained an appreciation of Hopper’s paintwork, because for the most part it’s uninteresting, something that always disappointed me. For a brief moment he experimented with more variation, using thicker paint and handling it wet-into-wet (see the tower of the lighthouse) or with a palette knife, which he usually reserved to represent plaster-work on buildings. But for the most part it he didn’t seem to give it a lot of thought (not that one finds very interesting paintwork in Eakins, who is always considered Hopper’s predecessor within American realist painting).

The description “realist” sits uneasily on Hopper, I think, if we take it to mean a painter who re-creates what is before him. The world is not as spare, clean or lacking in incident as his paintings, nor as composed. And we know that his wife, Jo, posed for all the female figures, regardless of their features, hair color or body types; and like Dorian Grey, the women remain young even as the model aged. But Hopper gave us paintings that show things as we imagine them, or remember them. Perhaps that counts as realism.

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her recent Philadelphia Introductions articles at inLiquid.