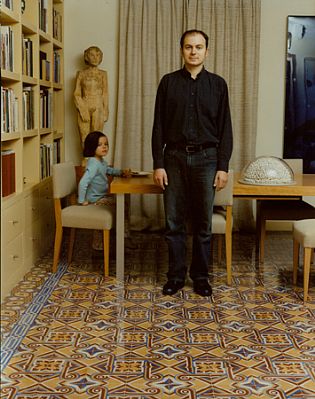

James Johnson, When I was a Kid I thought Mr. Rogers Could See Me Too

2006, detail,inkjet prints; on the monitor to the right is a video by Kara Crombie.

Photography is all over town–and there’s more on the way. From L’Autre, a group show at University of the Arts, to Tina Barney at Gallery 339, to James Johnson’s installation in the faculty show at Moore College, (not to mention Joel Katz’s 1964 photographs of Mississippians in the midst of the Civil Rights Era, also at Moore), to Eileen Neff’s eerie work at the ICA, I couldn’t help but think of how photography is increasingly slippery. Only Katz’s reportage from more than 50 years ago has the authority of what we like to think of as fact.

The work that’s totally outside the camera-as-reporter box is James Johnson’s installation at the galleries at Moore. Johnson’s prints would pass for reportage of the world around us, except he shrinks his digital prints into 1-inch images without frames, and sticks them all around two areas of the gallery. The amazing thing about the prints, at that scale, is they are surprisingly readable and invite you to enter their miniature world, kind of the way little television screens pulled you into the lives of the Cosbys or Edith and Archie.

James Johnson, When I was a Kid I thought Mr. Rogers Could See Me Too

2006, detail, inkjet prints

Maybe, with big flat screens, people no longer feel that way about the television screen. (Digression: or maybe it’s that Desperate Housewives and The Office are so darned arch that style eclipses emotions; we never quite believe in these characters in the same way that the nation believed in the Beav and in Ozzie and Harriet.)

But if you think about your iPod Nano, with its 3″ screen that displays a video, that shrinking of reality is more than ever a part of our world.

The name of Johnson’s piece is When I was a Kid I thought Mr. Rogers Could See Me Too. The feeling of being sucked into another zone of reality becomes a kind of poetry. The compression speaks to the body in Johnson’s piece–at once shrinking down and forcing you to peer into a minuscule space. But the little photos are dispersed widely enough to force a viewer to physically navigate them. The comparison of the micro and macro is surprisingly physical and mental. That duality allows the installation to accomplish something quite different from all the other self-contained photographs.

But the slippery slope of reality in photography is everywhere.

Thomas Ruff, Portrait (S.Kewer), c-print

courtesy Sender Collection –this print is enormous, and you the viewer, are staring directly at the subject’s chest.

L’Autre, at the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery at the University of the Arts, includes a surprising mix of power photographers and relative unknowns–Tanyth Berkeley, Alex Da Corte, Rineke Dijkstra, Suzanne Opton, Jessica Roberts, Thomas Ruff, and Sarah Stolfa. Roberts, Stolfa and Da Corte are local photographers. Curator Sid Sachs saw photos by Roberts at Nexus Gallery and invited her to be in the exhibit. And Alex Da Corte, on seeing what Sachs was up to, suggested his own work be included. Note this strategy, all you shy artists out there.

The works I found most exciting were by Tanyth Berkeley (she just opened Sept. 30 in an exhibit at MoMA) and by Roberts. Berkeley opens up the discussion of what is beauty with her probing photographs of young women. She reveals the downy hair on their skin, the imperfections of acne, their non-movie-star plainness, and makes a convincing argument that this is what it really means to be human and to be beautiful. Her work stands in sharp contrast to Ruff’s enormous portrait of a woman, Portrait (S. Kewer), and Da Corte’s mid-sized portrait, Nick (that’s artist Nicholas Lenker). Both of these portraits, against fashion-blank white grounds, acknowledge the power of the cultural ideals of beauty and allow the subjects to communicate some sexiness and the power of that beauty. Nick, however, still looks a little uncomfortable. But that striving to control the message and to create the ideal gives the images an element of fiction and posturing. On the other hand, Berkeley’s subjects are completely vulnerable to the eye of the camera, the photographer and the power of natural light.

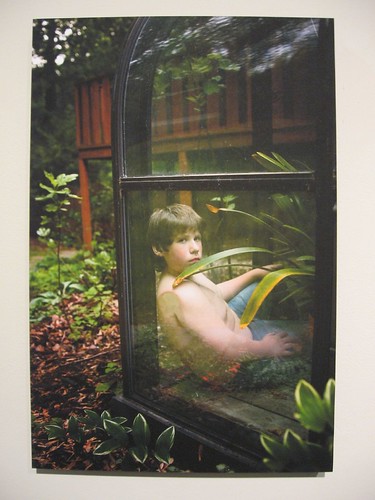

Jessica Roberts, Before the Coming: Ryan Andrew, 2006 digital print

Robert’s Before the Coming series of photographs of adolescent boys broke my heart with the boys’ vulnerability. Unless you know Before the Coming means before sexual maturity, it’s easy to interpret these as boys entangled in some religious cult. Either way, they are completely vulnerable and beautiful–at a time of their lives that society dismisses as transitional and homely, neither belonging to the realm of handsome real men, nor to the realm of beautiful little boys. And for me, they are best of show. I still get a lump in my throat just remembering them in my mind’s eye. I don’t know why, since the photographer has her own agenda, I find the truth of these photographs so impressive–perhaps because these kids are not pretending to be cool.

Suzanne Opton, Still Standing: Peter Kenny, 2001, archival pigment print

I don’t mean to dismiss the other images in the show. Of Opton’s Still Standing series of photos of New Yorkers after 9/11, I especially loved Peter Kenny, who is wearing not one ID but three. This photo got at something the others in the Still Standing series didn’t, that feeling and fear of being lost in the rubble. The others required more explanation.

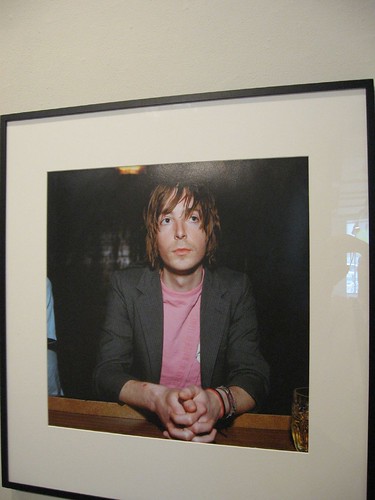

Ryan Smith, 2005, archival pigment print, courtesy gallery 339, philadelphia

Stolfa channels her subjects sitting at a bar, allowing them total control of their persona! And Dijkstra’s biannual series of pictures of Almerisa, revealing the child’s growth from a young immigrant to the Netherlands, to a young woman who is totally Dutch, is really not about the subject so much as about acculturation, differences, and acceptance.

All of these photographs are terrific. But taken together, they ask the question of what an image of a person can mean. Ultimately, I came away thinking that whatever each image means, it is not necessarily about the subject or the fact of a person before a camera. The photographs are slippery signifiers of what’s on the photographer’s mind.

Having just seen this exhibit, I went straight over to Gallery 339’s Tina Barney exhibit. Whatever I expected, I was wrong. Barney is pretty interesting. And talk about fact! Well, it’s pretty hard to know the facts that Barney offers up, but she gives lots of room for narrative speculation. People criticize her for pandering to the cushy lives, and in some of the photos she seems more focused on the cushiness than the humans. In the ones where the humans are key, however, the question becomes, are these really live action or is there complicity between Barney and her subjects. The gallery notes suggest there’s a degree of staging here, and a degree of spontaneity.

I simply don’t know the answer, just looking. But some of the images are fabulous. I was especially taken with The Standing Man, with its non-American decor, the relationship of the man to his standing sculpture on one side, a mysterious-looking modern sculpture under glass on the other, and his seated daughter balancing the collection spatially. This is Euro-chic par excellence, but it’s not the only thing Barney has to offer.

Another photograph, on Barney with her two sons standing around a barbecue grill, Tim, Phil and I, is incredibly strange for all its casual familiarity. There’s a sneakiness suggested in Barnes’ triggering the shutter without looking, and the focus on the bodies of the young men, the dwelling on their manliness, is unsettling. As for the shrimp on the barbee, it’s undercover, wrapped in foil, unlike the two young men. I don’t know that I’d trust her as my mother.

And yet, I doubt this tells a true story about reality in the Barney home.

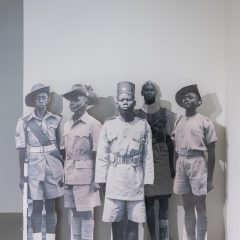

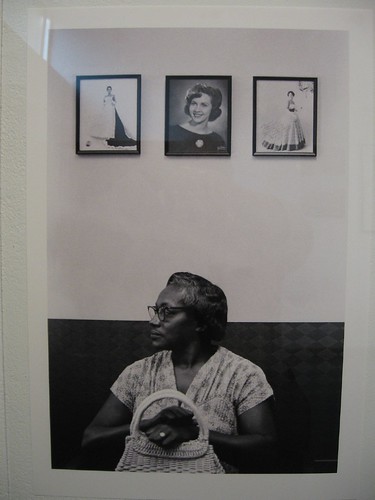

Joel Katz, from Mississippi 1964 series, Woman waiting to see the Special Assistant to the Governor, Mississippi State Capitol

Which brings me back to Joel Katz’s reportage photos at Moore, Mississippi 1964. These are earnest photographs that we are meant to take as reportage, but once again all reportage is as seen through the eyes of the beholder. A person with a different political agenda might have made different choices. None the less, I find myself appreciative of how straightforward Katz’s role is here–making choices of what to photograph with some intention of revealing the truth–his view of the truth.

And somehow, I think that’s every decent photographer’s intention–maybe. It’s just that these days, it’s a lot easier to create a whopper to tell that truth.

I haven’t seen the Eileen Neff show at the ICA yet, but Neff, with very different approaches, creates a reality that shimmers with a fifth dimension–i.e. not a reality at all. Also on my list to see–Women to Watch: Photography in Philadelphia will showcase new or recent work by Alida Fish, Neff, Clarissa Sligh, Ruth Thorne-Thomsen, Deborah Willis, Genevieve Coutroubis, Sarah Stolfa and Zoe Strauss, at Moore college, opening 10/25.