Post by Andrea Kirsh

[This is part 2 of a two-part post about public art. In this part, she reviews two books about successful New York public art programs–Creative Time and Arts for Transit. Here’s part 1]

MTA Arts for Transit

Artemis, Acrobats, Divas and Dancers (2001), by Nancy Spero, 66th Street-Lincoln Center, 1 line. Commissioned and owned by Metropolitan Transportation Authority Arts for Transit. Photo: Rob Wilson.

“Along the Way; MTA Arts for Transit” by Sandra Bloodworth and William Ayres (Monacelli Press, ISBN 1-58093-173-1) includes an eight page history of art in New York’s subways since their inception, then devotes most of the book to illustrations and short articles on 59 works. The back matter includes an illustrated catalog of art throughout the system, a list of pieces in progress and a bibliography of books, articles and reviews of the MTA art projects.

The historical text by the program’s current director (working with a museum curator) is vague about the administration of MTA Arts for Transit; it mentions that there was a move to revitalize the transit system in the 1980s which coincided with national discussion around public art and Percent for Art legislation. Henry Geldzahler was commissioner of the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs at the time and chaired the art selection panel, the book says. Readers will have to supply knowledge about Geldzahler’s intimate involvement with New York’s art world and his notable charisma; both likely contributed to the success of the program at that time. There’s a bit more discussion of the program’s administration in the final “Credits” which explains something of how it was embedded within the transit system; but that’s not a likely place to look for such information. The remainder of the article focuses on lessons the program has learned about choosing materials and siting art, and touches on interest in the public art field during the ’80s for artist/architect collaborations (which, they are honest enough to acknowledge, had limited success in practice). There is mention of artwork being commissioned through competitive process, but no details about the criteria or mechanism. Some of the short articles on each work have brief bios, but most focus on their contents and possible relations to their sites.

Harlem Encore (1999), Terry Adkins, Harlem–125th Street Station, MTA Metro-North Railroad. Commissioned and owned by Metropolitan Transportation Authority Arts for Transit. Photo: James Dee.

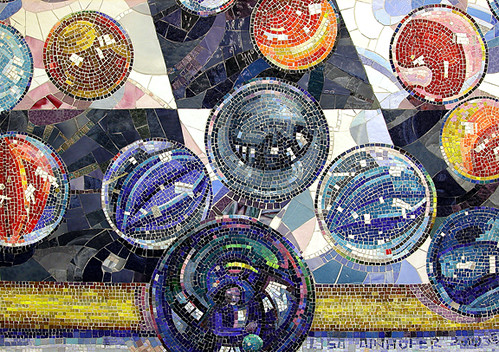

We have to turn to the handsome, full color illustrations (in most cases an installation shot plus detail) to judge Art in Transit’s success. As good as they are, photographs can’t convey the delight of coming upon a mural as the train pulls into a station or as you round the corner heading towards an underpass; the works that wrap around corners or are in multiple parts throughout a station are even more difficult to capture (although the Art in Transit’s interactive website makes the experience available virtually. I’ll only mention a few pieces I’ve actually seen: Lisa Dinhofer’s “Losing My Marbles,” a huge, cheerful presence in the subterranean warren beneath Port Authority; Nancy Spero’s “Artemis, Acrobats, Divas and Dancers” that cavort on the walls beneath Lincoln Center; Robert Kushner’s improbably-lush “Four Seasons Seasoned” which hovers above the turnstiles at Lexington and 77th Street. I haven’t seen Terry Adkins’”Harlem Encore” at 125th St., but intend to look for it; now there’s an artist with Philadelphia connections: Adkins teaches at Penn [Editor’s note: Adkins is currently in Ensemble, an exhibit at the ICA curated by Christian Marclay. Look for his upcoming perfomance related to that exhibit Wednesday, Nov 7, 5:30 p.m.]

Some of the artists are well-known, while I’ve not heard of others. Some works are figurative with obvious connections to the neighborhoods their stations serve; some are abstract, others conceptual. They represent artists of several generations and reflect the ethnic diversity of New York. While much of the work consists of glass or tile murals, artists have also designed architectural elements, fixtures and seating. MTA’s Art in Transit covers a lot of political bases and can still hold its head up within the art world.

4 Seasons Seasoned (2004), Robert Kushner, 77th Street, 6 line. Commissioned and owned by Metropolitan Transportation Authority Arts for Transit. Photo: Rob Wilson.

The book is beautifully-printed and the design by Think Studio, New York, is clear, tasteful, and restrained. That leaves the emphasis on the art it illustrates. As it should. I’ve made lots of notes from my reading and can’t wait to get an unlimited-use subway pass, so I can tour projects in stations I don’t otherwise use.

Creative Time: The Book

Creative Time, the book: 33 years of public art in New York City

The publication celebrating 30 years’ of Creative Time projects is as imaginative as everything the organization does.“Creative Time, the book: 33 years of public art in New York City” (Princeton Architectural Press, ISBN-13:978-1-56898-696-8) is an edition of 5,000, each with a unique cover generated by a mobile art project: the “Urban Visual Recording Machine” (2006). Mine (#630) was printed at 3:05 p.m., Sept. 9, 2006 at Madison Square Park; the cover records the ambient colors, volume of sound and the weather conditions at the moment, all translated into visual patterns. The book is a beautiful object throughout, thoroughly reflecting the organization’s visual sensibilities. It was designed by karlssonwilker, inc. and they should be congratulated for a design that truly reflects its subject and is visually exciting without sacrificing readability.

“Creative Time; the Book” is wordy, with texts by 21 contributors including artists, critics, public art administrators and curators; it intentionally represents multiple viewpoints, rather than reflecting the current organizational point of view. The book is directed at artists, students and art historians, anyone with an interest in public and experimental art of the past three decades and anyone who loves New York City. As Anne Pasternak, Creative Time’s current director, puts it: “We sought to reveal our motivations, explore our ideologies, even debate the contradictions inherent in our work.”

Doug Aitken: sleepwalkers, Jan. 16-Feb. 12, 2007, A Joint Project of Creative Time and The Museum of Modern Art. View in the sculpture garden, photo by libby

The volume names all 1,361 artists who have worked with Creative Time and includes a catalog of all 313 projects; many of the projects are illustrated and described at greater length throughout the book. The flow of the volume is non-linear and a bit messy, but that’s probably an appropriate format for the organization behind such diverse and unconventional projects as the city’s first drive-in theater (showing independent films), sited on a downtown parking lot (1978-9); sculpture and performances at a ‘beach’ created out of landfill from construction of the World Trade Center (Art on the Beach, 1978-85); artist-designed paper coffee cups distributed to delis throughout New York (2000-2002); and Doug Aitken’s “Sleepwalkers,” a multi-channel video piece projected on the external walls of MoMA, this past winter.

Creative Time describes itself as a “visionary cultural provocateur,” and its private status allows it to take risks that any public agency might shy away from. Its primary focus has always been artists: giving them opportunities and support to realize experimental projects in public spaces throughout New York City. The organization’s history is well recorded in Michael Brenson’s thoughtful interviews with Creative Time’s three directors: Anita Contini, Cee Scott Brown and Anne Pasternak; all acknowledge the few public agencies and the several private foundations that have consistently supported such experimental work (which neither generates income nor sticks around permanently to commemorate its patrons’ largesse).

Erika Rothenberg, Laurie Hawkinson, John Malpede, “Freedom of Expression National Monument,” Art on the Beach 6, July 7 – Sept. 16, 1984, Battery Park City Landfill

Photo © 1984 Lona Foote

That article and the conversation Ann Pasternak has with Tom Eccles and Tom Finkelpearl contain the clearest information on the philosophy of Creative Time, its position within contemporaneous debates about art, and what distinguishes it from other organizations in the public art field. Eccles and Finkelpearl both have experience in the area but rather different ideas about the relationship of the art to its audience–the “public” in public art. This book is a tremendously welcome addition to the literature on art of the past three decades when artists have questioned all the conventions of the field. By supporting collaboration, by blurring (or ignoring) the boundaries between art, performance, dance, film, architecture and fashion, and by siting all of its work beyond the conventional spaces of the art world, Creative Time has been at the center of the discussion. The book is valuable both for its insights and for the record it provides of 30 years of art projects that redefined both art and the public sphere in New York City.

Public Art Realities: Artists need to be paid

I did a bit of research, talking with administrators at various public art programs. As a very general rule, artist fees usually run 10 to 20 percent of the total budget (the remainder being for fabrication). If the artist is fabricator, s/he will receive the entire budget. From conversations with a number of artists in Philadelphia, the organizations commissioning art here are not paying them in line with national standards. The art projects at Eastern State Penitentiary are not truly public, in that one needs to pay admission to see them; but in format they resemble public art projects and a number of them have been very good. One artist mentioned being given $2,000 to cover fabrication and fee as well any ongoing care the piece needs; the artist spent more than that on materials alone. The program’s administrators must realize this, as should the public agencies and private foundations whose grants fund it. This is art on the cheap and on the backs of the artists, and it is not right.

Nor is it a way to commission world class art. The Cardiff and Bures Miller piece at Eastern State, which I referred to above, was not one of these paltry commissions; judging from its list of funders, the artists received considerably more than $2,000, and had an adequate budget to realize their ideas. Until the organizations in Philadelphia acknowledge artists as professionals who are entitled to reasonable compensation, I don’t expect things to improve.

–Andrea Kirsh is an art historian based in Philadelphia. You can read her recent Philadelphia Introductions articles at inLiquid.