Duke Riley, a drawing from his installation After the Battle of Brooklyn.

After seeing Kara Walker show at the Whitney Thursday, one of our goals of Saturday’s Chelsea run-around included seeing her work at Sikkema Jenkins. But we saw lots more,, and an awful lot of it had historical and political thoughts in it.

Riley’s submarine, modeled after drawings for such a vehicle from the pre-sub era. Roberta is checking out the insides, which, much to her surprise, had some beer cans strewn about.

Duke Riley at Magnan Projects was spectacular. Riley, if you remember, is a guy who has been conflating his personal history and obsession with New York history, creating a kind of museum that merges the two stories. He makes faux artifacts, drawings, mosaics, scrimshaw (he uses a tattoo gun), and videos, casting himself and his version of what happened in a heroic light. He’s kind of like Kip Deeds on steroids.

Duke Riley, Liberas Aut Mori, his drawing of a sub.

This show, The Battle of Brooklyn, includes among its artifacts a “submarine,” a hollow ball-like object made of wood, with a porthole or two, a dainty little rudder and a hatch at the top. Riley took a ride in the New York Harbor in his conveyance, The Acorn, which is based on a real Revolutionary War era sub. The Coast Guard espied him in his conveyance approaching the Queen Mary and detained him.

Included in the show is the video of his immersion and detention, including footage of the Coast Guard. The show also includes a couple of other videos, and some terrific drawings that weave space and time into Escher-like conundrums qua maps.

How Riley manages to make things look old fashioned and distressed and contemporary all at once is part of his magic, and he was decidedly the best thing we saw in Chelsea.

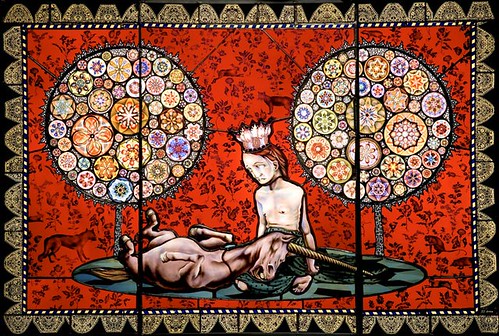

Work at Claire Oliver by Judith Schaechter, the Philadelphia stained glass lightbox master, looked spectacular and mysterious as ever–and really the main thing of interest that we saw that had no political or historical bent (other than art historical, like the above, with its reference to the Unicorn Tapestries). Schaechter, who defined Goth before Goth was a twinkle in a hipster’s eye, delights with patterned scenes of damsels in distress, insect invasions, Miss Havisham interiors and cats gone wild. Amazingly, she continues to perform all this without ever getting lost in the conventional.

Also worth mentioning is Thomas Demand at 303 Gallery, whose photographs this time, in his exhibition “Yellowcake,” were quite political (well, he’s often political, but not like this). Although as photographs of paper fictional tableaus they are less believable than previous pieces we had seen from Demand, this time the concept was dead-on with the visuals. The fiction surrounding the whole Yellowcake saga that led us into war in Iraq is a good pairing with Demand’s own fictions. And he has captured the anonymity of bureaucratic spaces in his from-memory renderings of the Embassy of the Republic of Niger, in Rome, the place where the paper trail of the whole sorry fiction about the yellowcake supposedly started.

Do Ho Suh’s installation at Lehmann Maupin

Do Ho Suh’s work at Lehmann Maupin didn’t feel like much of a departure from his past work, merging lots of small figures into one spectacular installation about endless humanity, a political comment if ever there was one. A smaller piece, although quirky, felt precious and moralizing.

A big disappointment were sculptures at James Cohan Gallery, by Folkert de Jong, the man whose styrofoam and urethane foam kilted figures were the rage at the Armory art fair in the winter. This time de Jong’s rough sculptures of circus performers seemed academic and short on concept.

Kara Walker at Sikkema Jenkens

And Kara Walker, who was an exhibit at Sikkema Jenkins, concurrent to her Whitney show, has mostly lost her sense of humor. A couple of days before we hit Chelsea, we had seen her work at the Whitney–including the spectacular and witty 1990s narrative silhouettes–parodies of racist subtext in genteel–and not so genteel–popular imagery from the past.

The work at Sikkema, like the silhouettes, continue her interest in skin color, this time moving away from parodies in stark black and white to a more literal range of browns and tans in between.

Kara Walker, Search for ideas supporting the Black Man as a work of Modern Art/ Contemporary Painting. A death without end: an appreciation of the Creative Spirit of Lynch Mobs – 2007

Ink on paper, 1 of 52 works: 22.5 x 28.5 inches each

The literal quality is a good pairing with Walker’s now bitter and hectoring words and brutal imagery. The locked down argument, even with its ironies and dark humor, squeezes out the sly ambiguities that made her previous versions of the story of race in America so engaging. Graphic elegance has given way to figure-ground struggles that began several years ago with still projections of jungly, kaleidoscopic backdrops behind silhouettes.

The Treasure Hunters, 2007

Mixed media, newsprint, cut paper on gessoed panel, 84 x 60 x 2 inches

There’s been a change in approach…from charm your audience while the skewer lies half-hidden beneath your cloak…to brandish the skewer publicly and let the blood flow. Past and present are conflated, and a looker might conclude that things are worse than ever in race relations in America (can it be so?).

Lost in all this is the fact that Walker is an equal opportunity critic of the behavior–and the hateful stereotypes–of everyone involved, including herself. It’s fair enough, but I wonder if anyone is listening.