Gijs Bakker’s Neck Ornaments as installed at the Philadelphia Art Alliance. From left: three Shoulder Pieces, 1967, aluminum, collection Stedelijk Museum’s Hertogenbosch, Stovepipe Necklace, 1967, anodised aluminum, collection Centraal Museum, Utrecht, Stovepipe Necklace, 1967, aluminum, collection Stedelijk Museum’s Hertogenbosch © Gijs Bakker, photo Matthew Suib

The Philadelphia Art Alliance is the only U.S. venue for a significant survey of jewelry by the Dutch designer, Gijs Bakker (organized by the Stedelijk Museum’s Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands and on view through May 18). Bakker is known in design circles for the collective, Droog Design, which he co-founded in 1993. Droog is a leader in the sort of quirky and intentionally-inelegant Dutch design that makes humorous and unconventional use of the vernacular, such as a lamp made of a milk-bottle or a Rietveld chair made of Leggo.

Bakker’s jewelry is no more likely to please customers of Tiffany or Harry Winston than Merce Cunningham’s dances delighted fans of Ballanchine. Bakker’s only interest in jewelry as either adornment or luxury goods is in their debunking. His jewelry is, rather, conceptual: jewelry as an exploration of the body and the various properties of his materials, which are as likely to be perspex, pvc, aluminum and newspaper as silver, gold and precious stones. His occasional forays into conventional forms and precious materials have a highly ironic tone and become critiques of jewelry business-as-usual.

The idea of jewelry as sculpture conceived in relation to the body has interested a number of Europeans since the 1960s (Bakker and Emmy van Leersum in the Netherlands, Otto Kunzli and Pierre Degen in Switzerland, Wendy Ramshaw in England, and many others), consistent with the pervasive cultural questioning that culminated in 1968. Art jewelry in the U.S. tends to emphasize virtuosic hand-work and craftsmanship within fairly traditional genres. While Bakker is interested in construction and his work is beautifully-made, he is not interested in handicraft. And it’s not clear that he ever expects these pieces to be worn any more than Betty Woodman expects her vase-forms to hold flowers or Picasso intended his ceramic jugs to hold wine.

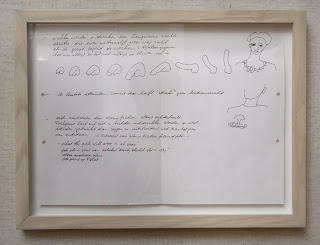

Gijs Bakker, Drawing for a necklace,© Gijs Bakker, photo Matthew Suib

The first room displays perhaps Bakker’s most conventional jewelry forms but also shows a group of working drawings. These enable us to follow his method of developing forms, so that a graphic figure might become a sculptural form and then a silhouette puncturing a flat surface. In one of the more humorous instances (above) he draws a sequences of male sex organs which finally become beads on a necklace (not exhibited, but illustrated in the exhibition catalogue). I wonder whether Dutch tailors, as do the English, ask their clients on which side the family jewels hang.

The second room contains a flat case with a grid of bracelets and rings linked by the common geometry of the circle. Bakker uses wood, plastic and mostly non-precious metals to twist, puncture and variously manipulate the forms. Some of his most dramatic works are the group called neck ornaments, but surely only a plumber could conceive of the Stovepipe Necklaces (above), collars made of aluminum ducting, as ornamental. Other designs look like prototypes of costumes for si-fi films. They define, exaggerate and certainly call attention to the neck as a transition between the head and the shoulders.

Upstairs the work is more consistently a commentary on jewelry as a social statement. There’s a life-size photograph of a diamond necklace worn by Queen Juliana of the Netherlands, imbedded in plastic to create a collar. Figures of soccer players cut out of newspapers are converted into ornamental pins and nude figures cut from reproductions of Michelangelo’s frescos are used as pendants for necklaces.

My favorites were a series of pins made in response to an advertisement for luxury cars, and Bakker named it after the caption: I don’t wear jewels, I drive them. Photographs of Ferraris and Jaguars cut from magazines and mounted in plastic are set with large opals, sapphires, diamonds and other stones to match the forms of windshields, bumpers or head-lights. Yet even these most blatantly-ironic commentaries on the culture of consumption were co-opted by the market: it turns out that most of the women who bought these pins were married to men who owned the very cars depicted.