Chris Burden L.A.P.D. Uniforms 1993 (edition 30), wool serge, metal, leather, wood, plastic, each uniform 88 x 72 x 6 inches. The piece was produced in collaboration with the Fabric Workshop, Philadelphia. The most dramatic installation I saw was when the piece hung in the L.A. County Museum of Art at a time when members of the L.A. police were on trial for brutality.© Chris Burden

An installation artist I know and respect received an audit notice last year from the IRS and asked me for a letter of support; the tax authorities apparently couldn’t conceive that an activity with expenses but no income might be a profession, and not a hobby. As I told the IRA: Installations have been among the most important of art forms during the past twenty-five years, yet until the artist achieves a great deal of attention they rarely produce sales. Because of their scale they can only be acquired by museums, or by collectors wealthy enough to have museum-like exhibition spaces. Installation artists must find venues and support their work by some other means (teaching, making frames, packing and transporting art, waiting tables…) during the long period, often decades, which might lead up to that sort of success; in that sense, it must be similar to composing symphonic music or opera. Those of us who care deeply for the arts are grateful that the artists are willing to endure this process.

I cited the example of Chris Burden:

In 1986 I organized the first museum survey of Burden’s work at the Lowe Art Museum, University of Miami. Burden had an international reputation by then and we borrowed three major installations and other works, all of them owned by the artist. No important pieces were owned by museums or collectors. The last time I saw Chris was two years ago, when I ran into him in Manhattan. He was there to help MoMA install a piece that they had purchased.

Burden’s acceptance and patronage by major museums was a long time in coming.

Chris Burden Medusa’s Head 1990 plywood, concrete, rocks, model railroad trains and tracks, 192″ diameter, collection Museum of Modern Art, © Chris Burden. This is the five-ton piece that Burden was installing at MoMA.

I thought of this again when I saw the extremely handsome, 415-page book documenting his work to date: Chris Burden (2007, coordinated by Fred Hoffman, Locus + Publishing, Ltd., distributed by D.A.P. Art Publishers, N.Y., ISBN 978-1-899377-18-3). The last large survey, and hence catalogue, of Burden’s work in the U.S. was twenty years ago; organized by the Newport Harbor Art Museum in 1988, it traveled to Boston and Pittsburgh. The lack of more recent documentation is particularly surprising since during the past twenty years Burden’s work has achieved ever more stature and importance.

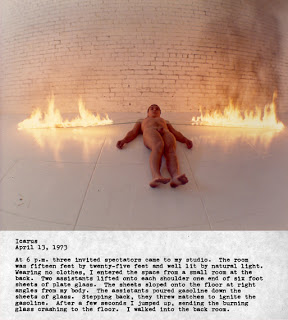

While Burden’s early performance work (1971-83) has received widespread if often distorted attention, his sculpture, installations and associated drawings have rarely been addressed as a group. Fred Hoffman worked with the artist and they organized the works thematically rather than chronologically, giving readers a scheme with which to approach Burden’s very diverse oeuvre. I might wonder about placing specific works under certain headings, but it’s a place to start and gives further understanding of the artist’s thinking. The topics and some examples are: communication (Full Financial Disclosure), shelter and structures (Exposing the Foundation of the Museum and the recent bridges), systems of transportation (Medusa’s Head), individual vs. collective (Five Day Locker Piece, L.A.P.D. Uniforms), confrontation and war (Shoot, A Tale of Two Cities), energy (The Fist of Light) and physical models of abstraction (Icarus, The Reason for the Neutron Bomb). Within these groupings each piece is illustrated and described by the artist. The book is beautifully designed and produced, and is as weighty as Burden’s output deserves.

Five authors contributed essays: Kristine Stiles discusses the central philosophical implications of light in Burden’s work; Robert Storr suggests that a central tension in Burden’s work comes from a confrontation between a typical boy’s play (with it’s striving for mastery as well as its violence) and an adult reconsideration of the same themes; Fred Hoffman analyzes how Burden has re-injected social and political content into artwork constructed with a Minimalist sensibility and recalls experiences working with the artist over the past 25 years; Lisa Le Feuvre discusses Ghost Ship and Paul Schimmel analyzes Burden’s use of drawings.

For more than thirty-five years Chris Burden has repeatedly tested himself and his audience with a series of questions addressing risk, power, technical prowess and control and social responsibility. His art continues to be challenging and disturbing. This very welcome volume records a major body of work which has been unknown in its entirety.