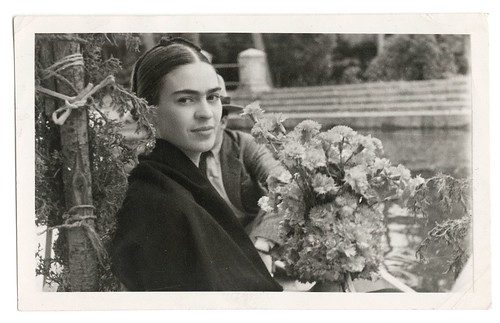

This is the third in three posts about Frida Kahlo, an exhibit at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.To read about films and books available on Kahlo, go to post 1 here. To read about the merchandise at the exhibit gift show, go to post 2, here.

The Frame, Self-Portrait, (ca. 1937-38). Oil on aluminum, under glass and painted wood, 28.5 x 20.5 cm., Image licenced to Nancy Meyer Walker Art Center by Nancy Meyer, © CNAC/MNAM/Dist RÈunion des MusÈes Nationaux / Art Resource

Frida Kahlo painted herself into her paintings as the heroine and high priestess of Mexicanidad, as well as of her own life.

It’s easy to love the Frida Kahlo show that just opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Feb. 20 to May 18)–it’s got the back story (or is it the front story?) of the unlikely love between two enormous egos and life-forces, Frida and muralist Diego Rivera, who both lived life large and a little wild. But to reduce this to a telenovela–the heavy breathing, the pain of life-threatening physical ailments, the infidelities, separations and reconciliations–is to miss the big story–the self-creation of Frida, the irreligious icon of Mexico.

The iconic images Kahlo paints of herself are not accidental. They are her way of raising her personal struggles in life to epic proportions. With that sainthood, of a decidedly corporeal nature, Kahlo sets the stage for numerous ways to make her story everyone’s story. Her intention was the story of Mexico and its people. But as Saint Frida, she allows anyone to fill in the blanks with their own personal woes and efforts, and her graphic qualities are a good fit with the pop imagery of our own time. She’s Wonderwoman with depth.

Frida Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931, 39-3/8 x 31 inches. (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art: Albert M. Bender Collection, Gift of Albert M. Bender) © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc, 06059, México D.F.

The contrast in scale between Rivera and Kahlo, only slightly exaggerated in this painting, is echoed in the contrast between Rivera’s enormous public murals and Kahlos small, detailed, autobiographical paintings.

The main, traveling part of the exhibit includes several paintings never seen outside Mexico prior to the opening of the show at its first venue–the Walker Art Center. Also in the exhibit, part of a cache of family photographs, many never before exhibited. The family snapshots paint their own kind of picture of a life full of verve and full of people–and of course, like all family photo albums, the pictures never tell you quite enough. But they do give a sense of the normal–a view never to be found in the self-dramatizing self portraits that have cemented Kahlo’s reputation in the popular culture. The photographic images prove just how fictionalized and ambitious those self portraits really are–very very very.

Frida Kahlo, Henry Ford Hospital, 1932. Oil on metal, 12-13/16 x 15-13/16 inches.

Collection Museo Dolores Olmedo Patiño, Mexico City © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

This image of Frida’s real-life miscarriage while Rivera was painting his famous murals in Detroit uses the retablo tradition and replaces the floating saints with concrete imagery related to the event and its location.

Here’s my list of why I love the exhibit–

1. You get to see the earliest self portrait and how it differs from the later work; the exhibit includes more than 40 paintings, a few not previously exhibited or seen before in the U.S.

2. You get to see–really see in fine detail–work that is otherwise familiar–the tiny dots of paint that make up the decoration on Frida’s shawl, the collage details that expand and challenge a sense of space. (Hey, did she use a magnifying glass or what? What tools did she use to control the minuscule scraps of paper? Tweezers?)

3. The photos, many from the Vicente Wolf Photography Collection, include a mix of family snapshots and some portrait photos by important photographers like Manuel Alvarez Bravo. Some of them also were altered by Frida, who didn’t like the way she looked in them, and yet she looks far more beautiful in any of these photos than she looks in her self-portraits!

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird/Autorretrato con collar de espinas y colibrí, 1940, 24-1/2 x 19 inches. (Nickolas Muray Collection, Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, The University of Texas at Austin) © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc, 06059, México D.F.

4. The degree of fictionalizing of Frida’s self-image becomes clear because of the juxtaposition to the photographs.

In those self portraits, Kahlo mythologized herself and the difficulties of her life, amalgamating the political with the personal. She brewed together the threads in Mexican popular culture–magical realism, folk art, Aztec imagery and Catholic bleeding hearts and saints–to affirm the power of the ordinary people whose culture bore those values. But by the merger of her own story with that of the nation, she avoided the kind of polemical one-note didacticism that usually plagues art with a message.

Frida Kahlo, My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree)/Mis abuelos, mis padres, y yo (árbol genealógico), 1936.

Oil and tempera on metal, 12-1/8 x 13-5/8 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Allan Roos, M.D., and B. Mathieu Roos digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc 06059, México, D.F.

The family tree’s Mexican landscape once again lifts this beyond the personal.

In the portraits Kahlo transformed herself, exaggerating the powerful eyebrows joined above the bridge of her nose and a delicate moustache, thereby giving herself a fierce power that undercuts any idea you may have of her being just a bauble decorated in Mexican finery. Those details also suggest that Saint Frida’s strength rests in her physical body. The effectiveness of her exaggeration is proven by how people keep coming back to those two details, worrying them, wondering about them. (In the curator’s walk-through, people asked if the details were deliberately masculinizing, referring also to a photo of her dressed in men’s clothes. People tried to tie in her lesbian affairs. But really, I think these details just place her beyond the ordinary while acknowledging the physical and power).

Frida Kahlo, My Dress Hangs There/Mi vestido cuelga ahi, 1933, oil and collage on Masonite, 18 x 19 1/2 in., FEMSA Collection, Monterrey, Mexico

To get a good look at the wonderful collage elements in this painting, you’ll just have to go to the exhibit.

Unique at the PMA’s Frida exhibit

The Philadelphia Museum version of the exhibit has a number of add-on features worth noting. A series of retablo images by anonymous artists hang just past Kahlo’s painting The Suicide of Dorothy Hale. Near the end of the exhibit is a display of pre-Columbian objects from the PMA collection in a vitrine along the right wall, objects similar to the kinds of works that both Kahlo and Rivera collected and used to decorate their house in Coyoacan (you can see where Kahlo used them in her still lifes, displayed opposite).

A hallway right outside the Dorrance Gallery shows Kahlo’s work in context of artists like Rufino Tamayo, Gulliermo Meza, Emilio Amero and highlights her influence on the 20th century Mexican modernists. Of course the two faboo Rivera murals in the Great Stair Hall add another piece of contemporaneous art making. And a catalogued exhibit of the art work of Mexican painter Juan Soriano is also up at the PMA.

Frida Kahlo, Itzcuintli Dog with Me/Escuincle y yo, c. 1938, 28 x 20-1/2 inches. (Private collection). © 2007 Banco de México Diego Rivera & Frida Kahlo Museums Trust. Av. Cinco de Mayo No. 2, Col. Centro, Del. Cuauhtémoc, 06059, México D.F.

The Frida Kahlo exhibit was curated by Frida chronicler Hayden Herrera and by Walker Associate Curator Elizabeth Carpenter, who, when I asked about Frida’s more unusual folk-wear, said that when you see a photograph of a crowd scene with Kahlo in it, dressed in her Mexican garb, you suddenly realize just how peculiar and outside the mainstream she is in her self-presentation. Both curators wrote essays for the catalog.

Philadelphia is the only East Coast venue for the show, which will move on to the West Coast at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art.

To read about films and books available on Kahlo, go to post 1 here. To read about the merchandise at the exhibit gift show, go to post 2, here.