Artist Kai Chan, whose work was exhibited at the Liao Collection, visiting the exhibition of Contemporary Korean Fiber at University of the Arts’ Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery and Hamilton Hall. On the wall is Shin-Ja Lee’s The Han River (1990-93), wool and synthetic thread, 65 x 1870 cm, a woven scroll that references traditional ink painting. The floor piece is Ja-Hong Ku’s Space (2001), silk, styrofoam, pins, dimensions variable. photos by the author.

Fiberphiladelphia, a city and area-wide celebration of fiber art attracted more than 200 national and international participants to a symposium last Thursday and Friday: Materiality and Meaning; Examining Fiber and Material Studies in Contemporary Art and Culture, held at University of the Arts. Coinciding with the symposium was the opening of an exhibition of Contemporary Korean Fiber at the Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery, one of 29 exhibitions associated with Fiberphiladelphia. Many of the Korean artists were in attendance and three Koreans presented papers.

Before the symposium I found myself talking to a tall woman who turned out to be fiber artist, Katherine Pannepacker, whose work I knew; she currently has an exhibition at the William Way Community Center at 1315 Spruce St. Pannepacker’s excitement in anticipation was visible – the symposia, she said, became better each year of the event. Sean Buffington, President of U Arts mentioned in opening remarks that the interest in fiber can be tied to our interest in the body (hair, fur,…) and Warren Seelig, a faculty member who co-organized the symposium suggested that this bodily association both attracts and repels us.

Seelig told the audience that he’d posited several questions to the speakers: Does the array of cross-media sharing threaten fiber as a discipline? do craft-associated materials need their own cannon? and is a back-lash against conceptual work giving more importance to materiality? The speakers seemed un-concerned with Seelig’s first question. While only Lydia Matthews drew her examples broadly beyond the discipline of fiber, the participants reflected an entrenched, institutional definition of the field.

As someone without a fiber background I was interested in how the area defined itself and what currently concerned fiber artists. After all, textiles and weaving have been taken up over the last forty years by artists from many other areas, and during a period when artists un-apologetically scavenged materials from all directions. Christo, Lygia Clark, Mona Hatoum, Claes Oldenburg, Martin Puryear, Robert Rauschenberg, Mira Schendel and Kiki Smith used textiles, and the list could go on indefinitely. Women often chose fiber as a way of overturning its association with traditional ideas of women’s work (Senga Nengudi, Faith Ringgold, Miriam Shapiro). The symposium participants and audience were overwhelmingly female, yet the question of gender never arose.

Amy Orr, who teaches at Tyler, displaying hand-made jewelry and scarf

The keynote speaker was Gerhardt Knodel who led the fiber department for 25 years at Cranbrook Academy of Art, which he subsequently directed. Materiality as a subject, began Knoedel, demands an actual object – at which point he removed his camel-colored jacket and donned a long Afghani coat made from silk ikat. He spoke of objects interacting with the world through use, and the history of this particular coat for him as well as the significance of its origin in a country beset by war since he had acquired it. Knoedel’s talk was ultimately an encouragement to pay more attention to both our everyday surroundings as well as the wider world, beyond our personal experience.

Knoedel’s coat brought out an irony for me, for while human use of fibers certainly begins with clothing, the Korean exhibition and most of the speakers’ examples included fibre that functioned as wall-hangings, sculpture, installations, everything, in fact, except clothing or functional objects. The fact that fiber artists have moved across genres made me wonder at Seelig’s concern that use of fiber by other disciplines might threaten the field. Those waters have been muddy for a while. The symposium speakers dressed largely in unadorned black but the audience reflected an embrace of imaginative clothing: devore velvet scarves, jackets made from ethnic textiles, various hand-loomed jacquards; fiber audiences are always artfully-dressed.

One of many symposium attendants wearing wonderful, hand-made textiles

Lydia Matthews, a cultural critic and dean at Parsons was delighted that fiber was now cut loose from a discipline and used by architects, designers, engineers and scientists. Materiality, she suggested, had become a means to another end, such as knowledge. She was also interested in the politics within which the material world is embedded, and showed an exciting range of examples in which craft became a way of forming communities: Fritz Haeg’s Edible Estates project of converting front lawns into kitchen gardens (Haeg was included in the ICA’s Locally Localized Gravity); Christine and Margaret Worthheim’s Institute for Figuring which carries out mathematical modeling via crocheting; Simon Starling’s work involved with ecology, immigration and trans-national trade; Rico23’s project with tribal populations in Brazil; and Stephanie Syjuco’s Anti-Factory and Counterfeit Crochet Bag Project, which engaged amateur knitters to produce hand-made, knock-off designer handbags.

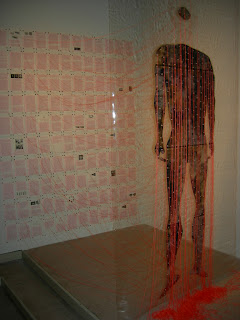

Zi Man Ahn Codebreaker & Codemaker (2006, poly-vinyl resin, cotton cloth, direct dye pigment, rayon yarn embroidery on book, direct dye on cotton cloth, 200 x 300 x 240 cm) at Rosenwald-Wolf Gallery

Sandra Alfoldy, craft historian of Nova Scotia College of Art and Design laid out a framework for studying materiality in terms of the materials themselves, how they are employed, their institutionalization, and how they are received. It was the latter that interested her. Alfoldy delved into the notion of truth to materials which has dominated the discussion of crafts and traced its moral imperative to Ruskin and Pugin. Popular reception of crafts is positive, she concluded, it’s only critical reception that’s the problem.

Artist, critic and curator Sun-Hak Kang suggested that materials try to escape a singularity of meaning through use,citing creases in paper which offer a metaphor of ageing, and hence life, and traditional patterns in quilting which suggest mandalas, and hence stability. Fabric, he said, is part of what it means to be human. Hyuk Kwon, artist and educator, displayed work by her students which emphasized the vast range of materials employed under the rubric of fiber: digital photography, imitation hair, hand-made paper, fiber-optic lighting, mother-of-pearl mosaic, rice, salt, noodles (dried, I believe), pine needles, and clothing brand labels.

Chung-Hie Lee Red Scroll (2005, dyed fabric, patchwork, handwork, hand and machine embroidery, 75 x 750 cm, collection of Clemmer and David Montague) in Contemporary Korean Fiber. The piece is in the form of a scroll painting and is displayed suspended from the wall and partially unrolled, in the lobby of Hamilton Hall

Chung-Hie Lee gave a particularly fascinating presentation on Pojagi as Material Expression. Pojagi are traditional Korean wrapping cloths, often made of irregular patch-works of small fabric scraps. They were so ubiquitous and quotidian that they escaped scholarly attention until the 1980s. Lee has taught pojagi in workshops around the world, and the quality and diversity of her student’s projects, which included clothing, blankets, wall-hangings and installations, confirmed her brilliance as a teacher.