I’m sure the irony wasn’t lost on Vito Acconci, finding himself an honored guest at the University of Pennsylvania, just about nine years after the Penn rejected a radical Acconci Studio proposal for a 1 Percent for Art project on campus.

The Penn powers that be weren’t quite comfortable with Acconci’s proposed little, shrub-covered African-looking huts for seating in front of the stores on 36th Street. (Acconci alluded to the African huts briefly during his talk.) They were shot down for blocking sight lines–thereby discouraging commerce and encouraging lurkers.

Ultimately, nothing got built on 36th Street, and the 1 percent public art commission ultimately went to Andrea Blum—hard-edged anti-tables and anti-chairs on 40th Street. Comparing the two pieces would be pretty instructive, if you ask me.

But back to Vito whose ground-breaking body art and installation work, with their consideration of politics and power, still influence art today. His influence is wide-ranging, also touching on video, audio, site-specific installation, everything that young sculptors are doing today. Just look through the Whitney Biennial catalog and make your own list. Or check out the previous generation, from Matthew Barney to Mike Kelley to Bill Viola to Marina Abramovic and Rikrit Tiravanija.

Vito is currently the subject of a scholarly exhibit at Slought Foundation, up until March 31. The exhibit, Powerfields: Explorations in the Work of Vito Acconci, was co-curated by Meredith Malone and by Christine Poggi, and is an outgrowth of Poggi’s curatorial practices class, which focused entirely on Acconci.

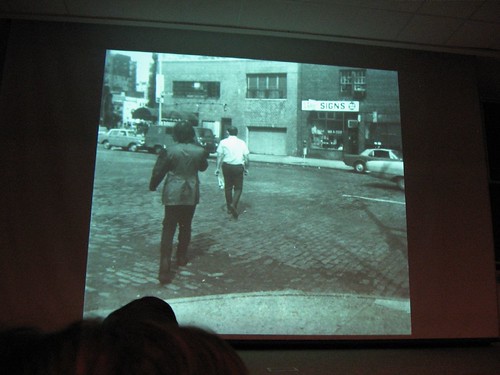

Acconci (in the suit) teaching.

In her introduction of the speaker, Poggi described much of Acconci’s work as utopian.

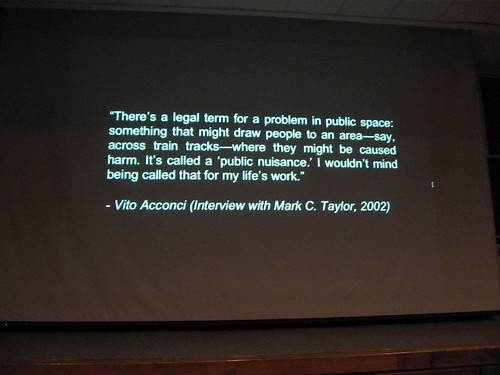

One of the warm-up images flashed before Acconci’s talk. A number of them had writings and quotes from him. This one says, “There’s a legal term for a problem in public space: something that might draw people to an area–say, across train tracks–where they might be caused harm. It’s called a ‘public nuisance.’ I wouldn’t mind being called that for my life’s work.” –Vito Acconci (Interview with Mark C. Taylor, 2002)

Famous for his edgy art actions/performances from the 1970s, Acconci is no longer that outrageous young man. He’s physically a bit thicker, a lot older. When he speaks, he repeats a phrase until he explodes into the remainder of his sentence–a delivery that suggests poetry, performance and a mental tic. He rocks back and forth. He’s intense and obsessive.

He described a career in which each new step meant rejecting the one before. He portrayed himself as someone whose art developed out of a series of philosophical crises, a series of manifestos that he undermined over and over until he rejected art altogether and switched to architecture (of a sort). Now he’s busy wondering about the architecture.

Here’s some of what he had to say:

Acconci the poet

He started out as a poet: “I wanted the words to be matter, to be material. … I was trying to make something as a fact, as literal as possible. The last piece that I thought of as a piece of writing, a 1969 poem [about a walk], was an attempt to make the reading time the same as the walking time the same as experiential time.”

One of Vito Acconci’s maximally literal poems.

Acconci the artist

Then he said he switched to an art context. “Art was a field you could imprint with anything from other fields.” An example he gave was using walks as an art material. He said he wanted to know “how to connect myself to the world around me, to the space around me.”

An example of work from this period was Street Works. “Every day I followed a person in the street until he went in.” The person’s reason for being on the street Acconci adopted as his own reason for being there. “I could literally be dragged by another person.”

Acconci said once he realized he was no longer writing, then the ground became the replacement for the page, the walk a replacement for the writing. “Why not shift focus from the medium, why not shift focus from the ground I walked on? Why not use myself? …I have to start focusing on me. The pieces in the 1970s, the pieces are turning on myself. I start an action; the action ends in me. The pieces all involve concentration.”

But Acconci then wondered how to prove that the concentration was on himself? His answer: “Apply physical stress on my body.” He made a film in which he used a moving candle to burn the hair off each of his breasts; he made one in which he pulled on his breasts–an exercise in futility. “I wish I could find an easier way to look like a woman,” he said, sounding rather earnest. He got a laugh anyway. The action “put me in the position of the Little Engine That Could. I think I can, I think I can. But no matter how long I pulled on my breast, nothing would happen.

The I and the You in Acconci’s art

Vito Acconci following someone on the street, one of the works in his Street Work series.

“I thought I was opening myself up to viewers. I was probably closing viewers off. The viewer is always a voyeur, looking in on some secret he or she shouldn’t be a part of.

“…I had to find a way to approach a viewer. This started to happen in 1971.” In Claim, the viewer could anticipate the situation he was entering with the help of video. But the situation, which invited the viewer to dare to walk down the stairs to the basement, involved getting past the blidfolded artist swinging a lead pipe. Acconci also talked threatening phrases non stop.

“I talk as a self-hypnotizing device. Whenever I hear someone coming down the stairs, I can swing the lead pipe.

“This was the beginning of architecture for me,” he said, referring to the way he was using and controling the space.

He said this was art as an occasion, and it was an exchange system between the artist and the viewer. “All of these I-you pieces, I set myself up as a still point, and you have to come through.

“It occurred to me that I was confirming an art world hierarchy, confirming all the things I hate about art–art as religion, art as an altar…

“…What if I started to blend in with the space?”

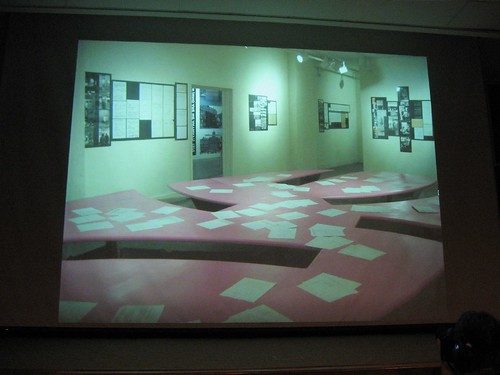

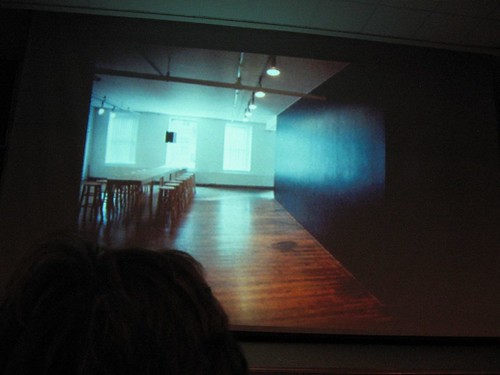

So in 1972, in a conventional gallery space, half way back in the gallery, Acconci made the floor rise to become a ramp that rose to 2 1/2 to 3 feet above the normal floor its highest point in the back of the gallery. Acconci hid beneath the floor for 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

“The viewer walks across the ramp. I’m trying constantly to masturbate. I can build sexual fantasies going on those footsteps. A viewer might be thinking, thinking, He’s doing this for me. My voice is constantly talking.

“Seedbed, it was a kind of 8-hour job for that period. Its sense had to do with taking a room, walls and floor that you assume are neutral, and trying to fill that space with a person. I had to be part of the floor–before the first person came and after the last person left.”

Suddenly, Acconci started talking about his musical influences–Neil Young, Van Morrison. “The single voice needing a long song to meander around the self. Music has always been a major influence on stuff I’ve done.” By the mid ’70s, his taste in pop during the installation phase included the Ramones and the Sex Pistols. However now, at Acconci Studios (his architectural phase), he listens to musici with no voice. “Architecture and music make an ambience. You can do other things while you’re listening to music.”

In the mid ’70s, he started making installations. “The way I saw installations, a space was given to me for a certain period of time. I didn’t think about what the piece would be until I already had a space. Why was site specific so important to me? Because that art couldn’t be universal; that art only made sense at this specific time.”

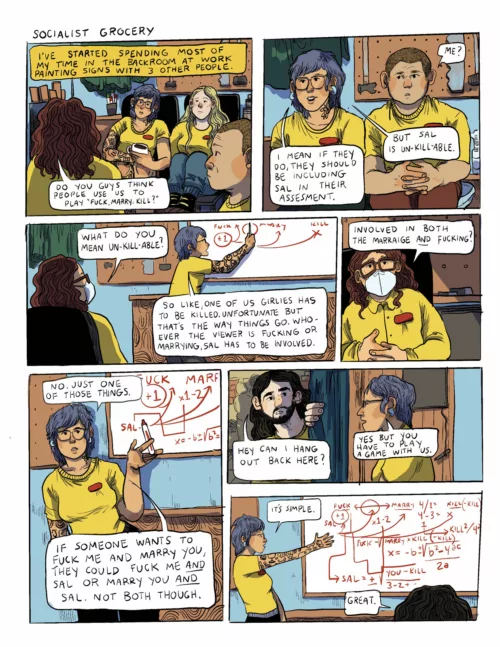

Vito Acconci, turning a gallery into a meeting place. The table goes out the window and becomes a diving board. His recorded voice repeats phrases like, “Now that we’re all here together, what do you think, Bob?”

He began to feel that in a gallery, which was a place to which people came, people had to be part of the piece, and he envisioned a space that was like a town square, with his voice calling people together. “I was kidding myself. A gallery will never be a public square.

“I couldn’t do art anymore.”

Vito Acconci, Instant House, with the walls down on the floor, only the American flag showing.

So Acconci became interested in architecture in the mid ’80s. In Instant House, if a visitor sat on a swing, his weight would raise the four walls from the floor, revealing a Soviet flag on the outside surfaces. On the inside was an American flag.

Vito Acconci, Instant House, with the swing weighted by a human being, the walls up, the Soviet flag, revealed

The search for a permanent home

But that wasn’t enough for Acconci. “The house only exists as long as a person [on the swing] keeps the instrument going. I wanted something permanent.”

Vito Acconci, Bad Dream House, his prototype permanent house

So he started making houses, like Bad Dream House. Once he made his prototype house, he decided, “So I needed a prototype landscape.”

“I became convinced that the stuff wasn’t art anymore. …I’m not an architect, so I needed to work with someone who was. …If I wanted to do something public, it had to start as public [i.e. made with others, working as a group].” He formed Acconci Studio eventually.

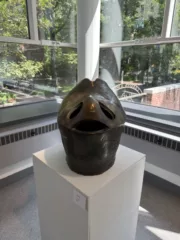

Spheres in use at Queens College.

In the ’90s, most of what he did were public, 1 Percent for Art public art projects, things designed for a specific building, a specific physical problem. An example he showed was for Queens College’s English Department front entranceway with two spheres, lost in a large empty space. He added more spheres, with cut-outs for sitting, a regular Acconci strategy, cutting away pieces of a geometric form. “The pass-through space has become a gathering space,” he boasted, then adding, “There’s a nagging doubt I have–Can a couple of folding chairs have done the same thing?

“Since I was doing public art, I was trying to give myself a reason for doing public art. Since there’s so much less money spent on the art than on the architecture, only one percent, maybe I’m bringing in something from the margins, bringing in a minority view.

What’s One Percent worth?

“But I’ve become convinced the art is worth only one percent of the architecture. Public art may be a folly.”

After that declaration of self doubt, Acconci kept talking about his other projects–a store front redesign and a hilarious tractor trailer called Mobile Linear City, with several trailer homes nested inside so they could telescope out to stretch the trailer from 15 feet to 75 feet. The walls would fold down to form the furniture, once the trailers were stretched.

“I don’t think I’m any good at details.” So the group process helps him overcome that problem, and he said plans evolve from discussions so it’s hard to say just who generated the scheme.

“I don’t think you can say six people think better than one, but you can say six people think more than one.”

Earlier in the talk, he had complained that his earliest body-based work came about 10 years too late. He says the same thing about architecture. “Architecture takes so long to do that it’s always outdated.”

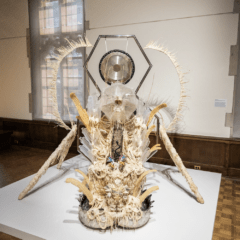

The Acconci Studio’s World Trade Center design, in which inside is out and outside is in.

He went on to show his group’s plan for the World Trade Center. “Make a world; then poke a hole in the world.” The model he showed looked like a hunk of Swiss cheese. “If a building is going to be exploded anyway, make it full of holes in the first place. “It can act as a kind of urban camouflage. A terrorist looking at it would say, oh, this is already destroyed.”

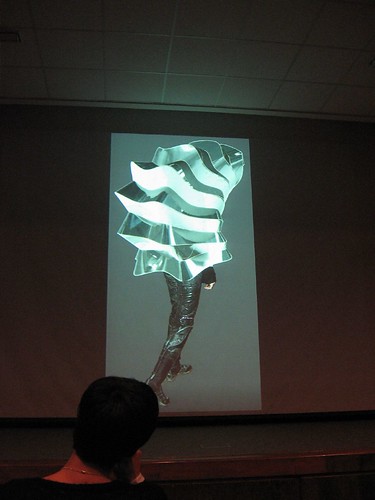

The Memphis performing arts center addition, which grapples with the concept of turning inside out and vice versa.

He went on to talk about other projects involving push and pull systems of manipulating materials. He showed a bench based on a mobius strip, a space designed to accommodate intermission crowds at a performing art center in Memphis. “I was interested in topological space in the ’00s.

A bench based on the idea of a Mobius strip.

“…The architecture we really want to do couldn’t have been thought of before the 21st century. It needs to be subservient to people. People need to sit.”

Acconci Studio, umbrella which doesn’t require hands and which reflects–a camouflage strategy according to Acconci

Then he started to talk about bending and folding and stretching materials in a “person-made island in Gratz” which was a theater and cafe. From there he began talking about designing clothing, including a different approach to umbrellas, a car that wouldn’t need tires or gas, and a soft car.

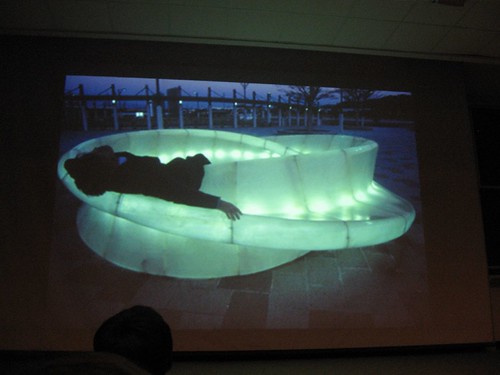

Acconci Studio’s person-made island in Gratz

“Blade Runner changed my notion of science fiction,” replacing the Stanley Kubrick all-white notion.

“Is architecture inherently a totalitarian activity? The hope of architecture is there’s always that renovation principal. Architecture is done by a sequence of people together, a series of people as time progresses,” he said, circling back to the problem of how out of date all buildings are by time they are completed.

But at least it’s not art. “There’s always the Do Not Touch signs in a museum–[suggesting] art is more important than people.”