Madonna Bedtime Story (1994, video) Madonna’s imagery for the most expensive music video ever was inspired by female surrealists like Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo and Frida Kahlo. Madonna had hoped (but failed) to play Frida in a film biopic.

Frida’s fierce, unflinching gaze

The first and most involved audience for art is always artists, and some artists have been a particularly fertile inspiration for others. Frida Kahlo is one, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art wisely assembled an articulate group of artists to discuss her influence on Sunday, April 9 in connection with the exhibition of her work on view at the PMA through May 18, 2008. They included Lesley Dill, Sarah McEaneany, Marta Sanchez and art historian Janet Kaplan speaking for Remedios Varo, whose biography she has written (Kaplan will talk about the biography on May 3rd at 3pm at the Taller Puertorriqueño).

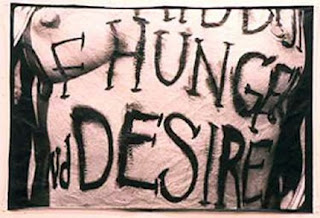

Lesley Dill Hunger and Desire (1998) oil, thread and wax on photograph, 49 x 77″, photo courtesy of George Adams Gallery

Frida’s fierceness, rawness and radiance inspires Lesley Dill, who made the marvelous comment that being influenced by other artists is like eating ghosts. Dill spoke of the sense of permission she received by recognizing something of herself in the work of other artists; Frida gave her permission to be both feminist and feminine, particularly in relation to dress and dress-up.

Sarah McEaneany invoked Frida’s unflinching gaze and the importance of details and colors as important to her. She described her work as being creative non-fiction. This might be a good description of Frida’s painting as well. McEaneany didn’t want this to be mis-interpreted as straightforward realism: I edit a lot, she said.

Marta Sanchez Retablo for Mister X, oil on metal, 30″ x 30″

The example of Frida as a painter and Chicana was crucial for Marta Sanchez, especially since being an artist had no validity within her own family. Frida gave voice to retablos, a form that Sanchez also draws upon (and like Frida, she uses metal supports – the traditional technique of retablos). She also valued Frida’s celebration of the every-day and her creating activist art that speaks for the voiceless.

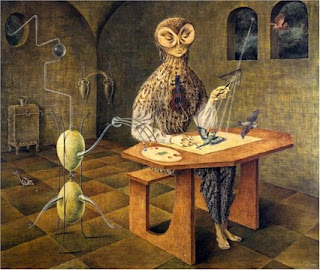

Remedios Varo The Creation of Birds (1958) oil on masonite, 20″ x 24″

Janet Kaplan gave some background on Remedios Varo, a Spaniard who worked in Mexico. At the beginning of the Spanish Civil War Varo went to Paris where she was an active member of the Surrealist circle and joined a group of Surrealists in Mexico City during World War II, where she met Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, and became especially close to Leonora Carrington. She remained in Mexico for the rest of her career.

Emily Hage, assistant curator at the PMA who moderated the discussion asked the panelists about the role of identity in their work. Janet said that Varo, who wrote a good deal, never spoke of herself as a subject. Sarah acknowledged that her work is unabashedly self-portraiture but hopes that others can see themselves in it, while Marta spoke of using self-portraiture as a window onto narrative.

In response to Emily’s query about the importance of understanding biography to understanding of artwork, Lesley gave a contradictory yet believable answer: she doesn’t think artists intend their work to be read with biographies attached, yet at this point she sees no distinction between her art and herself.

Artist’s Artist of the Nineteenth Century

Goustave Courbet The Wounded Man (1844-54) oil on canvas, 32 ½” x 38 3/8″, Museé d’Orsay, Paris; The artist portrays himself as a wounded duelist

Gustave Courbet (1819-1877) declared himself the proudest and most arrogant man in France; he was certainly the most controversial of artists as well as the one most revered by his younger colleagues who were concerned with advanced painting. Manet and Cezanne were deeply-influenced by his work which is also reflected in paintings of Renoir, Monet and others. One of the paintings in the wonderful current exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (MMA, through May 18, 2008) was owned by Matisse; another anticipates Balthus to a remarkable degree.

Gustave Courbet The Desperate Man (1844-45), oil on canvas, 17 3/4″ x 21 5/8″, private collection, photo © Michael Nguyen

This self-portrait is in the tradition of Rembrandt (and Messerschmidt), who made faces representing extreme emotions by looking in the mirror.

The MMA exhibition is essential for anyone who doesn’t thoroughly know Courbet’s art and offers great pleasure and insights for those who do. The first room portrays a young artist fashioning his public image; he did 20 self-portraits between 1842-55, and twelve are assembled here. Courbet works his way through various Romantic conceits (mad genius, wounded dueler) and invokes his own artistic heroes:two versions are based upon portraits by Titian. After seeing The Desperate Man I’m just waiting for Johnny Depp to play Courbet.

The exhibition doesn’t include Courbet’s major statement of his artistic position: The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory Summing Up a Seven-Year Phase of My Artistic Life ( Museé d’Orsay, Paris; the huge work could not travel safely), but has enough important paintings to satisfy anyone. Several aspects of the exhibition offer fascinating insights, particularly for contemporary viewers. It includes several unfinished paintings which are of interest because they’re the only way to know how a painter proceded in developing ideas.

An article in the catalogue offers further insight into Courbet’s technique: radiography documents the fact that he made numerous, substantive changes as he painted and created his canvases out of patchworks of previous paintings. While Velazquez and other painters often adjusted the size of their canvases as they worked by adding strips along the edges, no other major painter composed with such a collage technique as Courbet. He also painted over not only his own works, but re-used canvases by other artists.

Julien Vallou de Villeneuve Reclining Nude no. 1939 (1853) salted paper print from paper negative , 4 13/16″ x 6 5/16″, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, purchase Lila Acheson Wallace Gift, 1993

The exhibition also reminds us that Courbet’s work was controversial because of issues of decorum (appropriateness; a long-standing requirement of art) that will not at all be obvious; while some recent art has aroused major controversy, it has not been because it addressed an acceptable subject in an unconventional manner (thinking of the row over Chris Ofili’s Madonna, that last comment may not be true). The labels do a good job of explaining just what shocked nineteenth-century viewers of paintings such as Courbet’s rather sedate depiction of three women and a girl in a landscape (the MMA’s Young Ladies of the Village (1851-2).

Gustave Courbet Reclining Nude (1862) oil on canvas, 29 ½” x 37 1/4″, private collection. This is one of several nudes in the exhibition derived from photographs which are also on view.

Another interesting aspect of his work made clear throughout the exhibition is the use of photography. Picasso is claimed to have said good artists copy; great artists steal. And they steal promiscuously. Like any great artist, Courbet found ideas everywhere, from great paintings to pornographic photography. The exhibition includes the range of photography from which he stole; to view the photographic precedent for his long-underground close-up of a woman’s crotch, The Origin of the World (1866, Museé d’Orsay, Paris) which is in the exhibition, you’ll have to bend over and look into a stereoscope, as the pornographic image was intended to be viewed.

Gustave Courbet The Wave (1869) oil on canvas, 43 11/16″ x 53 3/16″, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie. From a technical perspective, it’s superb said Balzac of The Wave; Cezanne called this version one of the discoveries of the century.

The exhibition, which is arranged thematically (portraits, nudes, landscales, hunting pictures) also includes variants of many of the subjects, emphasizing that while Courbet’s painterly originality was prized, the uniqueness of each painting wasn’t. Painting was work, and if a client wanted another head-on view of crashing waves or a landscape of The Source of the Loue, he’d oblige; the exhibition includes five versions of the latter.