Libby and I had coffee with Max Mulhern the other day. Max, a Philly-born artist living in London (and prior to that Paris for many years), was in the area to buy a boat, a sailboat that he and his family will sail up and down the Eastern seabord this summer. More on that in a minute.

Max is an energetic sort who’s very knowledgeable about art and loves to talk about it. (He’s a friend of Paris-based ex-pat artist Matthew Rose whom I met in 2006 when Steve, Stella, Max and I were in Paris — and that’s how he came to get in touch). We sat with Max at Cafe Ole talking about Modernism and contemporary art and whether anyone but trust-fund folks can afford to be artists these days. Libby and I love to yak about art (who knew?) and so we all were having a jolly time.

Then Mulhern told us he was thinking of moving his family to Philadelphia and wanted some advice on galleries and such. When we asked about the kind of art he made he pulled out a small wooden box tied with a ribbon and said there was a sample of his work inside. He untied the ribbon and I took the lid off the box (small tea box from China) and inside were little white objects, maybe 20 or more all packed together just so like chess pieces.

Box in background holds the small wooden pieces.

As we took each little wooden block out Max would tell us its name. Each block was a mini-pedestal and they all were non-functional — pedestals that were split in the middle or had flip-top tops or were skewed in some way to make them individuals with personalities — and not dumb lumps that sit under art.

When out on the table, the works had achieved critical mass and people in the cafe came over to ask us what they were and where could they get some. Because they look like game pieces people wanted to know what the game was. Max, interested in people’s engagement with the work, told them it was any game they wanted it to be and they could play it any way they wanted.

The one figurative element on the table, a tiny plastic female figure with an upraised cudgel seemed to activate the set by adding a narrative touch. Was she a police woman? a security guard? a soldier? With her low tech weapon and snappy uniform she was a cavewoman/cop and you could spin any kind of story you’d like. But even without the figure the group of pedestals had narrative possibilities. Like chess pieces they were markers that could be positioned in relation to each other in a way that conveyed power relationships and that’s a story.

Max said he had studied up on the origin of pedestals in art when he was teaching a class and became intrigued. The story has to do with Hermes and herms, the god of travelers and a pile of stones and a phallus that somehow segued into a statuary base and into the innocuous pedestals we now know. He told us he’d been thinking of installing a group of his pedestals — made to real-scale — in a space and had already done an ad hoc performance with a pedestal in a London subway station where he hired a guard to stand watch over one of his pedestals. He gave the guard a cudgel to hold just like the cudgel the tiny figure holds. People leaned on the pedestal and after awhile the guard left the post and went away. Now there’s a game for you.

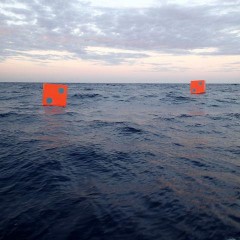

As for the sailboat, the artist explained that he’dspent his summers growing up on the Chesapeake Bay where he helped his father work on boats. He loves the water and now, when he’s living on a boat somewhere, he often makes ephemeral floating sculptures that he leaves behind when he sails on to another location. He will be making floating sculptures during his time here this summer. Ephemeral floating sculptures and pedestal games — if you think we were intrigued you’re right.