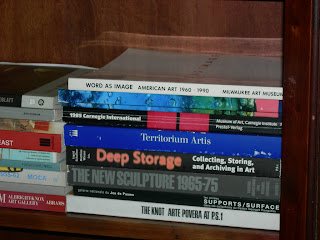

Catalogues to biennials, triennials and other round-ups of contemporary art are fairly standard in format: glossy and large, with the emphasis on the pictures. I can see a group of them on the bookshelf opposite (below), stacked on their side because they can’t stand on a shelf less than 11 or 12 inches high.

The catalogue to the current Carnegie International, Life on Mars , is something else.

(Life on Mars; 55th Carnegie International, ISBN 978-088039051-4; for reviews of the exhibition see Libby’s and Roberta’s posts). At 9 1/4 by 6 2/4 inches, it could be an anthology of poetry or a bible, the resemblance reinforced by three place-markers stitched into the binding. This book is meant to be read. It’s a striking volume to hold and flip through; the cover is bound with patterned fabric resembling a night sky and the names of all 40 artists are on the spine. The cover’s pattern is repeated as background for the table of contents which are printed in remarkably large type (as is much, but not all of the text) and the sections are divided with transparent paper in acid, 1960’s colors. I wasn’t surprised to find that it was designed by the Dutch firm COMA, who also designed a stunning recent monograph on Marilyn Minter.

The text includes the expected illustration of each artist’s work accompanied by 3 or 4 paragraphs by Max Andrews and Heather Pesanti, as well as an essay by the curator, Douglas Fogel. There are further essays by Daniel Birnbaum, Richard Flood and Chus Martinez and numerous artists’ writings, helpfully distinguished from the usual catalog apparatus by different type-faces and bordered pages. These begin, surprisingly, with Jonathan Swift’s satire of 1729, A Modest Proposal, still shocking in its suggestion that a cure for Ireland’s destitute masses was to sell their infants for culinary uses; other artists’ writings include previously-published as well as new pieces by Thomas Schutte, Fischli and Weiss, Thomas Hirschhorn, Paul Thek and Mario Merz, among others, and a conversation between Paul Chan and Eugenie Joo.

Unfortunately, the essays are less than satisfactory. Fogel suggest that [Swift’s] satirical critique of British colonial brutality becomes, in light of current events, a kind of allegory for life in our contemporary world…. Swift’s text speaks with surprisingly [sic] lucidity to the situation we find ourselves in today,…we still eat our own children. Swift used the image of the sacrifice of infants (with all of its biblical references) neither as metaphor or allegory but to create an image of England’s abuse of its Irish colony that was sensational enough to command attention. Fogel’s employment of Swift’s imagery ignores its pointedness and rhetorical brilliance and does nothing to explicate contemporary events or artists’ responses to them. Few of the exhibited artists make critiques nearly as pointed or incisive as Swift and no one in the catalogue writes as well; Swift is a hard act to follow. Fogel adds a stream-of-consciousness of associations: Night of the Living Dead, Goya’s black paintings and Disasters of War, Cormac McCarthy’s The Road and Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. These may clarify Fogel’s thinking but his article does nothing to address the exhibited work.

The other curators also seem to think that citing a range of philosophers, theorists, writers, artists and filmmakers (some well-known, others obscure) substitutes for analysis, as if they are supposed to get credit for their reading and research. The artists’s writings are better, not pretending to be criticism. Matthew Monahan can string together a series of citations into a narrative as a re-enactment of Walter Benjamin’s archives. Ryan Gander’s Loose Associations Lecture, a frankly-dissociated string of very interesting observations, has the didactic clarity of a lecture and benefits from illustrations. Joo’s interview with Chan, who is not in the exhibition, covers his major project, Waiting for Godot in New Orleans and allows the artist to discuss his motivations, reservations and process; it presents a particularly-clear discussion of one artist’s attempt to locate a socially-conscious practice within a badly-broken world.

Perhaps one should just concentrate on the pictures after all.