Fishing lures collected by Mark Dion on display at Bartram’s Garden; some of them look like teething rings.

Artist Mark Dion has staged an installation inside the 18th century house at Bartram’s Garden, a wonderful historic treasure on the banks of the Schuylkill. The installation is right at home here.

Dion, who is known for art work that relates to collecting and the museum as an institution that skews and preserves cultural memory and knowledge, has shown his work at MoMA, the Tate and the Carnegie in Pittsburgh, to name a few.

A turkey vulture in one of the collection cases.

Here he has put on display quirky artifacts–from seeds to carcases to tourist kitsch–that Dion collected while following in naturalist William Bartram‘s footsteps through the South at the time the Revolutionary War was brewing, in the 1770s. William is the son of John Bartram, America’s first native botanist and the original owner of the estate on the Schuylkill. The project was conceived and commissioned by Philadelphia curator Julie Courtney.

By bringing William Bartram’s methods to today’s Southern landscape and culture, Dion creates a kind of archive that turns out to be provocative, intense and accessible.

The artifacts serve as a diary of a road trip, the equivalent of postcards mailed home, shells stuffed in pockets on a stroll along the shore, and tourist mementos. But this tourist is trying to record more than just his trip. He is trying to capture a changing location and an era as reflected in specimens both cultural and natural. The seriousness and wit with which Dion collected these “snapshots” elevate them to both a revelation of a region, but also a revelation of the artist and his thinking.

Dion made charming naturalist-style drawings of insects and leaves–and golf carts. He brought back alligator knickknacks, collected at flea markets and along the road. He brought back an eel and a snake, a dried turkey vulture, and a list of birds spotted along the way.

A handmade specimen cabinet Dion found on his travels. Check out the nail drawer pulls. This may have been my favorite item in the display.

The collections of specimens are on display in cabinets, some belonging to the house, others supplied by Dion, including a handmade cabinet he found on his journey, a specimen of its own kind.

Dion trying to prop up one of the parcels he stamped Hate Archive. This stamp, mimicking a “fragile” rubber stamp, didn’t seem to bother the U.S. Postal Service. I consider this classic postal art! One the other hand, some innocuous specimens of river water, packaged in medical specimen containers, raised suspicions at some rural post offices.

One cabinet displays his hate archive–the items remain in their postal parcels, never to be opened. “I had the urge to buy them to remove them from discourse, in a way. They shouldn’t be opened,” he said as he led me around his collection. He was a little vague about what was inside, but implied it was racist kitsch. As he spoke to me, he kept trying to prop up one of the parcels, which fell repeatedly. “I must find a solution,” he said. Metaphorical!

Just as Dion took me around from collector’s case to collector’s case, an interpreter will take you around when you visit the exhibit. The experience is more Academy of Natural Sciences than ICA. And that’s what Dion intended. He wanted it to be accessible to all audiences, and not just art lovers. But collecting as a Contemporary art practice does have a long history, from Marcel Duchamp‘s readymades to sculptor Dario Robleto‘s phonograph records and bones. Dion, however, is thinking about what it means to collect and then what it means to institutionalize the collection in a museum.

The house at Bartram’s Garden dates to 1731 and was built by William’s father John Bartram.

“The house is incredibly important, said Dion. “I didn’t want to screw up this house with Contemporary Art. …I chose to do a modest intervention, with different rooms showing material culture and specimens collected. William Bartram went to the natives and made treaties. I went to flea markets.”

It’s because of Dion’s modesty in relation to the history here that this exhibit succeeds so well.

Dion and some of the specimens he brought back.

“Others have followed Bartram’s trails, so what I was interested in was the notion of collecting. Instead of an enlightened gentleman from England as a patron, I had Bartram’s Garden, Pew, and the people of Philadelphia. My mission was to bring back material culture and natural artifacts and not interfere with the story that Bartram’s house tells. It’s a historic, real house here.”

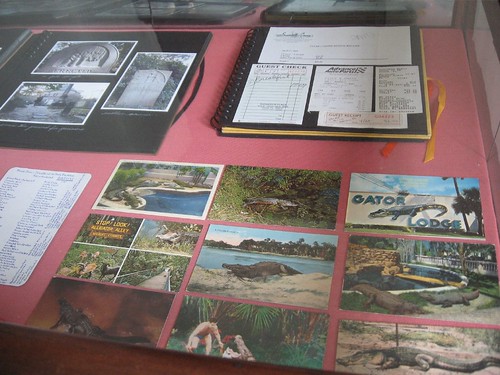

From top left, clockwise, photo album, receipts, purchased postcards and a list of birds seen on the journey.

Here are some excerpts from what else Dion had to say:

L: How long were you on the road for this project?

MD: Five weeks and three weeks. I’m still not really done. …John Bartram sent back animals, insects, turtles. He was a paid collector, sponsored by John Fothergill, an English gentleman with a passion for plants. There was a great interest at that time in all things novel. People would try to naturalize their gardens in England. Bartram sent back drawings, active seeds, live plants and ethnographic objects.

Bartram also traveled with and wrote about Native Americans. He had a sympathetic point of view. He was also a seasoned outdoorsman and traveled with friends on his strenuous expeditions.

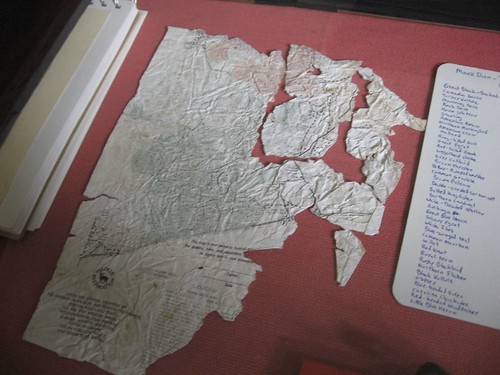

A map that fell in the water, leaving the travelers high and dry for how to get where they were going.

L: So what surprised you on your travels?

MD: I had lots of preconceptions; I imagined Florida as all strip malls from the Keys to Georgia, from the Atlantic Coast to the Gulf Coast. It’s not true. There are beautiful stretches. Extraordinary landscapes are still left there. Traveling is one of the most interesting way of knowing, and the landscape exceeded my expectations.

Bartram’s landscape does not exist now. There is Payne’s Prairie, South of Gainesville, but most of the landscape is gone. That’s what I anticipated. On the other hand, I was surprised by what survived. I was surprised by how herrings adapt to living life on a golf course, how alligators adapt to living life in drainage ditches, how ibixes survive in Disneyland–the flexibility in their behavior.

…William Bartram was the first to perfect our most important genre, creating the travelog or the road movie–like Easy Rider, and Jack Kerouac, On the Road. He was an incredible artist.

Some of the alligator knickknacks on display at Bartram’s Garden. These are in display at a case that is part of the house.

L: Can you tell me a little about why you collected so many bits of alligator kitsch?

MD: The alligator is a symbol of Florida. Most of the alligator kitsch is passe. Very little of it is new. [Re the alligator ashtrays] Even the ashtray itself is an endangered item.

Dion brought back a bunch of pine cones, eaten to the nub by red squirrels.

L: How did you select what you sent back?

MD: I chose things related to tourist culture–postcards, packages to friends. [He compared the return addresses to GPS coordinates and maps.] I have an affection for sending and receiving things by post.

The landscape has changed dramatically since John Bartram’s time. And before that, it had changed dramatically from since the Spanish landed. It has always changed very dramatically. [William] Bartram wrote about it as changing not for the better. Natives, before the English arrived, lived in an equilibrium with their environment. That changed with trade, with killing not just the animals they ate, but killing all the animals to trade their furs. The British introduced trading, introduced a modern economy. When Bartram traveled, everything south of Savannah, south of Charleston, was Indian territory, and west to Mobile.

Bartram returned from Charleston in 1777. Because he had a British patron, he felt unsafe once the revolution started.

While I was there, a discussion about getting a bigger jar for this snake ensued. Where, I asked curator Julie Courtney, was she going to buy a snake jar? I’m thinking Edmunds’ Scientific. But her answer was Fante’s, that old, quirky kitchenwares haven in the Italian Market.

Dion’s exhibit, Travels of William Bartram–Reconsidered, opens tonight, 5:30 to 8:30, and will remain up through Dec. 6. But go now, while the weather is warm, and take in the garden as well as the exhibit!

Here’s the project’s website, made in collaboration with Dion’s wife, Dana Sherwood, and Lime Projects. It is discursive and inclusive, with all the highs and lows, endless videos and too much information. It too is an archive, so there’s a lot in there–without the witty editing that makes the installation itself so charming. It has some navigation shortcomings, something I find quite amusing, given that navigating is its subject. For my taste, I’d skip it and go straight to Bartram’s.