Rhythms of India; the art of Nandalal Bose at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA) is an eye-opener; this is the first exhibition outside Asia of the artist considered the father of Indian modern art. That concept bears some pondering; while modernism in Europe was marked by rejection of an exhausted academic tradition, for Bose and his generation the first priority was to recover the tradition of Indian art and Asian art in general that had been denigrated by European colonial overlords. His modernism consisted not only of the project of recovery but of the individualism of his ensuing production and the choice he exercised in working across a variety of styles.

Bose was acutely aware that European painting was based on shadows and perspective used to create illusions of three-dimensional forms and space whereas Indian painting employed linear definition of forms and had always been comfortable with degrees of abstraction. Bose was also tolerant of the artistic borrowings of earlier Indian art; one of the Indian traditions he looked at was Mughal miniature painting which was based on Persian prototypes. He found inspiration in the great, fifth-century Buddhist wall-paintings at Ajanta as well as various indigenous folk art but equally studied the monochrome ink painting and watercolor techniques of China and Japan. This liberalism in choosing artistic forebears in the name of artistic nationalism goes beyond anything seen in the West (or indeed in modern China).

Nandalal Bose Darjeeling Fog (1945) tempera on paper, 24 1/2 x 14 5/8 in., National Gallery of Modern Art, New Dehli

The exhibition, organized by the San Diego Museum of Art and bound, after Philadelphia, for a tour throughout India provides a crucial visual context for Bose’s work. It opens with an Indian painting produced under British rule that reflects European academicism: Ravi Varma’s depiction of Hindu gods in modern dress, done in Western oil paint and intended to be circulated as a varnished color lithograph. It also includes paintings by Bose’s teacher Abanindranath Tagore and other Tagore students and ends with a number of younger artists who studied with or were influenced by Bose. The labels contain significant information which is supplemented by two good, didactic videos within the galleries and an excellent catalog with essays by multiple scholars on the artist, his artwork, writing and teaching, the search for a new Indian art, his relationship with Japan and his concerns with a pan-Asian culture.

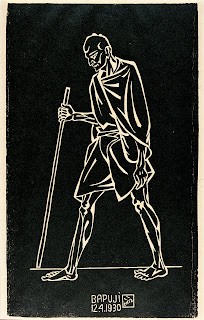

Bose was involved with the most important figures in the formation of the new Indian state. His teacher was the nephew of the major poet, Rabindranath Tagore who chose Nandalal to be the first director of the art school at the university he founded at Santiniketan. Through Tagore he met Gandhi and the two of them shared a belief in the importance of India’s rural village. Nandalal became the only artist Gandhi patronized and his woodcut image of Gandhi on the Dandi march has become the most iconic image of the leader.

Nandalal Bose Dandi March (Bapuji) (1930) linocut on paper, 13 3/4 x 8 7/8 in., National Gallery of Modern Art, New Dehli

Bose’s work is extraordinarily varied; the exhibition includes sketches from life in ink and/or pencil on postcards and life-size ink drawings of figures from religious literature. There are colored paintings on paper and silk, monochrome ink paintings on paper, preliminary sketches and cartoons for wall paintings, illustrations for a children’s book, posters for the Indian National Congress in 1938 (made from local colors on handmade paper), woodcuts, linocuts and a book reproducing Nandalal’s illustrations for the Indian constitution. I can think of no other national constitution with hand-painted illumination.

Nandalal Bose Floating a Canoe (1947) ink on paper, 13 3/8 x 32 1/2 in., National Gallery of Modern Art, New Dehli

The work is equally diverse in its style, reflecting high art and vernacular influences from the history of India, China and Japan. Despite two visits I’d have a hard time identifying a work as Bose’s but the exhibition makes clear his lifelong quest for recovering a people’s history and dignity through art, and it is an absolutely fascinating journey to follow.

Multiple Modernities; India 1905-2005

Upstairs the PMA has a smaller exhibition of a number of Indian artists whose concerns about national identity and individual expression parallel Bose’s. Multiple Modernities; India 1905-2005 was organized as part of a seminar taught by Prof. Michael Meister at the University of Pennsylvania. A number of the works are from the museum’s collection which benefitted from the fact that the late Stella Kramrisch, curator of Indian art from 1954-1993, began her career teaching at Rabindranath Tagore’s university at Santiniketan.

It opens with a rare group of drawings by Tagore who only began to to draw and paint in his sixties. These include works in pencil, ink, crayon, watercolor and even oil (a woman’s head which fills the entire sheet and may be a portrait of Kramrisch). Some artists in the exhibition were interested in work by village painters and several Kalighat and Santal paintings are shown as well as work by the urban artists influenced by them.

This exhibition, like the one of Nandalal Bose, is both interesting and difficult, in that the work is so unfamiliar. It’s hard to recognize sources when even they are barely known. The labels include biographical information and discussion of the subjects and also situate the artists as to their concerns, sources , style and relationship to each other but I found discussions of the art particularly hard to assimilate. Western interest in Indian art has focused almost entirely on work of the past. While the current generation of Indian artists participates freely in the international art world, Indian artists earlier in the twentieth century were involved with intensely national concerns and there’s a lot of catching up to do to appreciate them fully. This is one step in that necessary process since globalization is not a one-way street.