Richard Misrach, Untitled #704-03, 2003, Chromogenic print mounted on plexiglass

74 ¾ x 115 ¼, Courtesy the Artist; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco; Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Los Angeles; and Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

I stumbled on Sand, the show at the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton. It sounded like just the ticket for summer vacation art.

The exhibit of more than 50 works inspired by sand as a material or a metaphor meanders through time and tastes, including terrific contemporary work and some more conventional stuff from art historical biggies and smallies–from Picasso to Pollack to Fairfield Porter. But the work that intrigued me were mostly contemporary works, especially photographs and sculptures.

Jasper Johns, Memory Piece (Frank O’Hara), 1961–1970, Wood, lead, brass, rubber, sand, and Sculp-metal, 18 3/8 x 6 ¾ x 13 (open), Collection of the Artist, © 2008 Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, N.Y.

My favorite piece, by Jasper Johns, is a cast of the sole of poet Frank O’Hara‘s foot embedded on the inside cover of a sand-filled jewelry box so that each time the lid swings shut, the foot imprints the sand. Several years after Johns made the cast, a beach vehicle struck and killed O’Hara at age 40 on Fire Island. That bit of history turns the piece into a funny and sad memorial that reaches beyond the artist’s original intention.

It’s no surprise that the usual sand cliches–footprints, sandcastles, hourglasses and the grain of sand as minuscule and infinite–all receive a serious workout in this show. What is surprising is that so much of the art still manages to inform anew.

A huge Richard Misrach chromogenic print–an overhead shot of a sunworshipper isolated in the middle of a vast sea of bumpy and track-marked sand–invokes the vastness of nature and man’s place there, for starters. A pair of photos of sand-dune-filled abandoned homes in Namibia by Richard Erlich place the sands of time into a historical context and show the surreal in the factual. Both of these photographers document reality as viewed through their personal lenses of beauty and wonder.

(above)

Mariko Mori, Empty Dream, 1995, Six color photographs, 108 x 288 overall, Collection of Jerome and Ellen Stern, New York

(below)

Gabriel Orozco, Carta Blanca, 1999, Sand, cans, and labels, Dimensions variable, Marieluise Hessel Collection, Hessel Museum of Art, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y. © 2008 Gabriel Orozco/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

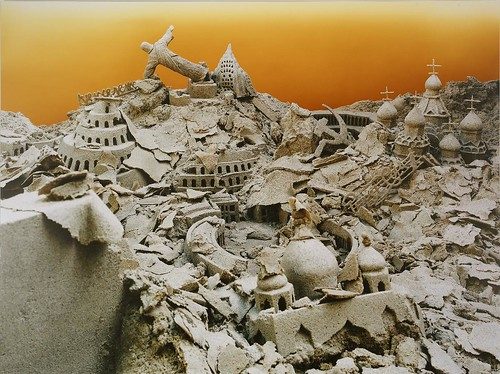

Photographs make their own reality in Mariko Mori’s six-panel photo, Empty Dream, and Liset Castillo’s Pain is Universal but So Is Hope (Orange). Mori embeds herself, costumed as a mermaid, among the bathers at an actual Japanese artificial beach. Given how improbable the beach itself is, the mermaid seems right at home. Castillo’s half-smashed sandcastles (models of iconic structures from around the world, dominated by Rio’s Christ figure on the verge of collapse) beneath a gorgeous orange glow suggest we’re all going to hell in a handbasket. The tension between what’s real and not real here has the reality of world politics and wars just below the surface.

The goofy pranksterism of Dennis Oppenheim‘s 1970s body art is now almost a cliche, but it still evoked a smile in me. Oppenheim photographs the pale rectangle left on his skin by an open book, after five hours on the beach.

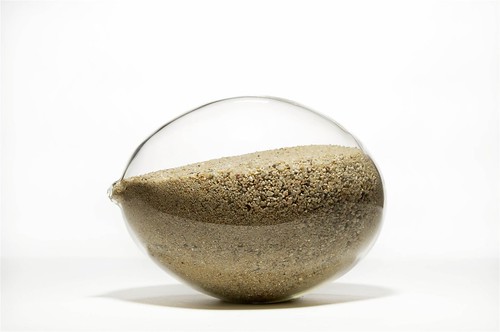

Jochem Hendricks, 6,128,374 Grains of Sand, 2003–2005, Sand and blown glass, 10 x 6 ¾ x 6 ¾, Courtesy Haunch of Venison, London, © 2008 Jochem Hendricks/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The sculptures didn’t pack as strong a punch as the photos. But a nice pairing by curator Alicia Longwell are Donald Lipski‘s 210,000,000 Grains of Sand and Jochem Hendricks‘ 6,128,374 Grains of Sand. Lipski’s sand fills a glass-sided box, Hendricks’ a blown-glass ball. True to the affects of their pieces, Lipski claims to have extrapolated his number from the number of grains of sand in a cubic inch, a nice match to the science-terrarium look of his container. And Hendricks claims to have paid minimum-wage workers to count the grains, five grains at a time, a nice match to the more humanistic look of the glass globe, which has a bit of sag like a breast or a water balloon weighed down by its contents. Lipski’s piece has a local connection–Philadelphia collector Terry Hyland.

Andrew Clemens, Sand Bottle, 1879 (front view), Colored sand in glass bottle, 8 x 2 ½ x 2 ½, Collection of C. Wesley and Shelley Cowan, Terrace Park, Ohio

The show had some wifty inclusions that I also enjoyed. A couple of rather Gothic anonymous drawings of the same landscape at different times of day were made of charcoal on sandpaper, both contributed by Matt Mullican, who also had a piece of his own in the exhibit. A 19th century sand-painting in a bottle, created grain by grain, by sideshow performer Andrew Clemens, is a patriotic tour de force. And a contemporary peephole installation by Manfredo Berninati of a room piled with junk, a sand table and a classical-style sculpture of sand looked like a 19th century artist’s studio as a playpen.

The exhibit has a bunch of notable artists in addition to those I mentioned–Ed Ruscha, Alex Katz, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, Winslow Homer, Milton Avery, Ana Mendieta, Joseph Cornell, Roy Lichtenstein, David Smith, Ashley Bickerton, Lynda Benglis, Vija Celmins, Ernesto Neto and way more.