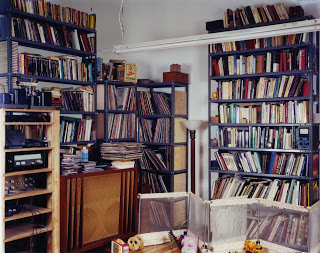

Moyra Davey Long Life Cool White (1999), C-print, 20 x 24 in., collection of the artist.

Catching up with my trip in June to Boston and Cambridge, MA (see post) I didn’t yet mention an impressive photography exhibition at the Harvard University Art Museums, Long Life Cool White, the first museum showing by Moyra Davey. There were three bodies of work, all in color: a wall-sized grid of well-worn pennies whose marks of use resembling desert landscapes or craters on the Moon are studies of difference within sameness; a sequence of New York City small-scale commercial operations (newspaper booths and lower East side shop windows with amusing hand-lettered signs in Yiddish); and a large sequence of interiors of a residence, the artist’s own, I presume. The pictures are modest in scale, eschewing the emphasis on virtuosic printing that characterizes much recent photography.

I’m someone who always looks at the walls and bookshelves of people who invite me to their homes, so of course I enjoyed the leisurely perusal of Davey’s interiors and the stuff of her everyday life. It’s the home of an urban sophisticate with an interest in the arts: imported coffee, a poster for a Jacques Tati film, post-cards of a Lucian Freud painting and a self-portrait by Ilse Bing, lots of defunct stereo equipment and old lps, endless cheap metal shelving with books piled one upon another and volumes of Chekhov, Cheever, Rilke and Sartre.

Moyra Davey Early (1999), C-print, 20 x 24 in., collection of the artist.

Davey often titles the images after a single item within the picture: Long Life Cool White is the manufacturer’s name for the fluorescent bulb which hovers above one scene. Perhaps the reference to light is significant, for Davey’s poetry of the everyday employs an unusual palette for color film, with an emphasis on whites and the limited color saturation fluorescent light produces. Many of the small still-lives are obviously constructed for the camera yet the views aren’t prettified: unruly electrical cords dangle from an overloaded outlet and dust bunnies accumulate beneath a bed, revealed with artless candor. The series doesn’t read like a catalog of spaces or possessions. It comes off rather as a slightly amused self-portrait, with books read, music heard and domestic accouterments as fond markers of the artist’s past. The museum produced a beautiful, small book with the exhibition (Long Life Cool White; photographs and essays by Moira Davey, Harvard University Art Museums and Yale University Press) containing an introduction by curator, Helen Molesworth, and an essay by the artist Notes on Photography and Accident; the book and exhibition remind us of the significance of private space and introspection in a world dominated by noise and public spectacle.

Photographs in Dublin

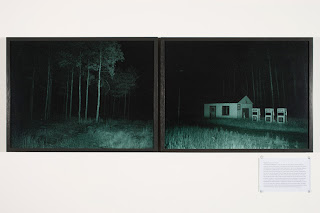

Sven Johne A Walk in Lusatia (12 to 17 June, 2006) Wanderung durch die Lausitz (12 to 17 June, 2006 (detail) five diptychs and corresponding texts, infrared photography, photo courtesy of Project Art Center.

In Dublin I saw several interesting exhibitions in Temple Bar last week, all of which included photography. The Flight of the Dodo at Project Arts Centre featured an international group of artists. According to curators Jonathan Carroll and Tessa Giblin it was made up of various artworks and elements that celebrate adventure, delve into factual myths, plunging in and out of notions of the hybrid, evolution, imaginative escapism, the will to survive and ultimate extinction. The title is an oxymoron, for the extinct bird was famously flightless.

The most compelling work was a series of infrared photographs with texts by the German artist Sven Johne purporting to investigate a herd of sheep whose slaughter the local villagers attributed to wolves. Wolves had been thought extinct in the area for over a century, and Johne’s nighttime vigils revealed no predators but rather artifacts of various extinct human activities. The stories had a hint of The Twilight Zone and it was hard to know whether Johne’s detailed narratives should be taken as fact, but the combination of stories and ghostly nighttime images made for an uncanny look at place and history and questioned the knowability and factuality of both.

Martin Clegg The Meadows (2008) courtesy of Gallery of Photography

Gallery of Photography showed work by three emerging artists and I found Martin Cregg’s the most interesting. His cropped views of suburban-style housing built in formerly rural areas turned them into minimalist compositions with serial variations on right angles. The tone of the work was unclear: ironic criticism or formal appreciation? One particularly interesting shot showed a pastoral landscape as background to the ruin of a recent structure being invaded by weeds. It was a view of real beauty that managed to avoid the Romantic cliche of nature reclaiming the land from human intervention.

Ken Gonzales-Day Golden Chain (2005) Ektachrome print, 60 x 75 in., unique print, photo courtesy Temple Bar Gallery.

Temple Bar Gallery and Studios brought together an international group of artists around the theme Under Erasure. With a nod to Derrida the selection concentrated on photographic work. None of the artists employed the obvious erasures of Stalin’s retouchings of the historic record in which “the commissar vanishes” (to use the title of David King’s book on the subject: The Commissar Vanishes: The Falsification of Photographs and Art in Stalin’s Russia). Rather, they involved images of buildings erased by being cut up to construct silhouettes of imaginary cityscapes (Richard Galpin) or being overprinted (Idris Kahn’s “Every page of the Holy Quran” where the entire text collapsed onto one sheet renders it illegible), and texts erased with white-out (Candice Breitz, who created suggestive but elliptical stories from selected words on the pages of an erotic novel). The most interesting project involved the recovery of an erased history by Ken Gonzales-Day. He researched the suppressed history of lynchings of Mexican-Americans in California and sought out their locations. His wall-sized photograph of an ancient tree re-inscribes the landscape with a forgotten history of violence. One can’t help but think of the similarly-enlarged trees of Rodney Graham and Tacita Dean which seem shallow by comparison. Gonzales-Day has also produced a book on the subject (Lynching in the West:1850-1935 Duke University Press, 2006).