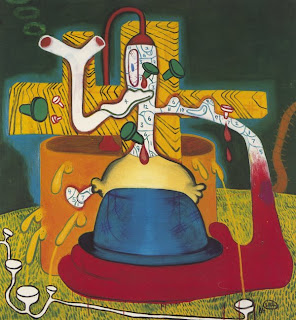

Peter Saul Donald Duck Crucified (1964) oil on canvas, 63 x 59 in., collection Karen E. Tappendorf

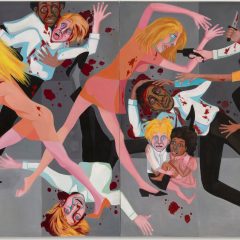

When Jeff Koons’ work sells for millions and Paul McCarthy’s chocolate butt plugs do brisk business at an international art fair, it may be hard to remember that not too long ago some art had the power to offend. Peter Saul’s anger directed at American social and political mores, delivered in a style wrought from popular culture (Mad magazine to Disney) and with his finger often directed at the eye of political correctness, did offend. And the offense outlasted all of those younger artists who are indebted to him.

I always do things the wrong way, which is completely empty territory.

Peter Saul (1980)

The only time I’ve seen a group of his work on museum walls was in Amsterdam, in the huge Stedelijk Museum exhibition, Eye Infection (2001-02), where he was shown along with H.C. Westerman, Jim Nutt, R. Crumb (whose work is currently on view at the ICA at Penn, see Roberta on the exhibition, and her opening night video) and Mike Kelly. The exhibition did not travel to the U.S. and it has taken this long for U.S. museums to acknowledge him. A major survey was organized this summer by the Orange County Museum of Art and will be shown at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) Oct. 18, 2008-Jan. 4, 2009.

Not to be shocking means to agree to be furniture.

Peter Saul (2008)

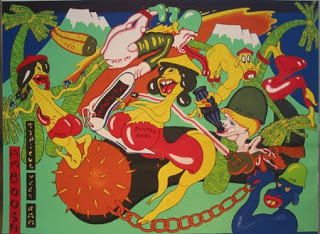

In preparation I looked at the catalog. Peter Saul (Hatje Cantz, ISBN 978-3-7757-2204-9) is a handsome and beautifully-illustrated monograph whose plain, grey paper-covered binding reflects the lack of pretense that the artist conveys in his writing and interviews. The essay by the exhibition’s curator, Dan Cameron, reviews Saul’s biography and production considered within the history of its reception. In a long interview with Robert Storr the artist discusses his education and unusually independent career as an artist, made possible by his early meeting with dealer, Allan Frumkin, who bought his paintings outright through their thirty-year association. Storr and Saul also talk about the development of Saul’s painting, artists that interested him (from Paul Cadmus to Rosa Bonheur) and his turn to political subjects in the mid 1960s.

It’s the intellectual dignity of modern art that upsets me, excites me to paint as I do.

Peter Saul (2008)

Michael Duncan places Saul within the tradition of American history painting, or the painting of big ideas, from Emanuel Leutze to Thomas Hart Benton; I would also place him with others of his generation such as Lenny Bruce and his friend and editor, the self-described investigative satirist, Paul Krassner. While Saul’s early works, with subjects from the domestic realm, were inevitably associated with pop artists, Saul was alienated from their pretense of neutrality. According to Duncan, Saul wanted to incite and repel. Duncan discusses the influence of two Missourians, Thomas Hart Benton for his swelling, mannerist compositions and populist reception, and Walt Disney for representing motion through extended body parts, as well as for his audience. He suggests that in Saul, a fallen imperial America has found the history painter it deserves.

Peter Saul Stalin (2008) oil on canvas, 78 x 108 in. courtesy of the artist and David Nolan Gallery, New York.

The catalog includes the expected back matter as well as a recent essay by Saul on his process of conceiving and executing his paintings, and a 1967 letter to curator Ellen H. Johnson, rejecting her sound, art world advice. Saul explains that he will continue to paint work that is accessible to a broad audience beyond the art world and include explicit allusions, rather than hint at his subjects. Various hand-written statements by the artist, some cited here, are used as dividers throughout the volume.