Martin Puryear Self (1978) stained and painted red cedar and mahogany, 69 x 48 x 25″, Joslyn Art Museum, Omaha, Museum purchase in memory of Elinor Ashton, © Martin Puryear

When Brian O’Doherty famously described the white cube that is the setting for much contemporary art it was to critique its ideology, the illusion it fosters that the art it encloses is separate from all life outside, separate from history, society, labor, commerce. But the white cube is also an architectural space and that profoundly affects the art as well. This was dramatically brought home when I saw the Martin Puryear exhibition at the National Gallery of Art (NGA, on view until Sept. 28, 2008 before traveling to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art). I saw the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) which organized it, and didn’t feel the need to see it in D.C. until my friend and colleague Ann Hoenigswald convinced me otherwise.

Martin Puryear A Distant Place (2005), basswood, yellow cedar, white pine, and maple burl, 15′ 3/8″ x 35 3/4″ x 35 3/4″, collection the artist, © Martin Puryear, image courtesy Donald Young Gallery, Chicago

I remember entering the exhibition at MoMA, taking a long appreciative look, and turning to the first guard I found to inquire whether the artist had installed it; I’d never seen sculpture so sensitively arranged. Puryear had, of course, and would do so again in Washington. His placement accounted for each grouping of work fully in three dimensions and all of the sight-lines from one room to another. But MoMA’s galleries are the ultimate white cubes: windowless and featureless, with flexible but character-less lighting.

In Washington Puryear wisely, but against all expectation, chose to site the bulk of the work (forty pieces) in the Gallery’s original, neo-classical building rather than in I.M.Pei’s East Building, where six pieces overflow the main exhibition rooms. Puryear used a u-shaped sequence of rooms which visitors can enter from either direction, emphasizing the lack of frontality in his sculpture. I entered at Fourth Street and climbed the stairs to see A Distant Place (2005, above) with what looks like an over-sized narwhal’s tusk standing vertically, sited in the center of a square marble hall. Behind it two putti played in the fountain of a landscaped courtyard and the long, central hall of the second-floor galleries stretched beyond. This clearly announced the resonance the sculpture would have with its surroundings.

Turning right, the first room held three pieces whose elegant but obviously hand-worked carpentry (raw wood, pegs and exposed laminates freely on view) contrasted with the polished wood floors, marble baseboards and traditional molding on the walls. In the second room the elongated, vertical tongue-like element of Lever No. 1 (1988-89) rose like a plant attracted to the natural light from the skylights. With far fewer pieces within eyesight than at MoMA, each sculpture assumes more significance and the experience of seeing them is more intimate.

Martin Puryear Some Tales (1975-78) yellow pine, ash, and hickory, 13′ 1 ½” x 32′ 93/4″, Panza Collection, © Martin Puryear, photo copyright Giorgio Colombo, Milan

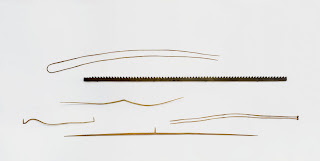

Puryear’s installation emphasizes a visceral interaction with the sculpture. The smaller galleries never hold more than three pieces. The giant Desire (1981, above), in a room to itself, is placed at an angle, encouraging visitors to walk beneath the axle attached to its giant wooden wheel. Two other galleries are particularly stunning: in one the long walls hold Some Lines for Jim Beckworth (1978), long pieces of twisted rawhide that call to mind the knotted counting strings used by various indigenous Americans, and opposite it Some Tales (1975-78, above), which read like a song of praise for simple, wooden tools; the last or first room, depending on where you enter, is octagonal with two openings. The remaining six walls hold a series of Puryear’s elegant hoops, emphasizing the 3-dimensionality of even those pieces which flirt with 2-dimensions.

Martin Puryear Dream of Pairing (1981) painted pine, 51 ½” x 54 ½” x 2″, Alice Kleberg Reynolds, San Antonio, TX, © Martin Puryear, photo Roger Fry

MoMA and the NGA are both restrained in their presentation, allowing the work to speak for itself; but it speaks in a different voice in the Gallery’s very different surroundings. If you think you know Martin Puryear’s work, take another look.