Periodic Table designed by Theodore Gray; a large multi-image version is included in the new museum at the Chemical Heritage Foundation.

If the word chemistry provokes a reaction somewhere between boredom and fear, think again. The Chemical Heritage Foundation (CHF) at 3rd and Chesnut has opened a new museum designed, as they put it, for adults who don’t remember or understand chemistry. They’ve done a smashing job! The museum will also appeal to serious younger visitors, but unlike the playground atmosphere that’s the Franklin Institute, this is filled with loads of information and lots of artifacts. The permanent exhibition Making Modernity addresses the contributions of chemical and molecular innovations to paint colors, Bakelight jewelry, nylon stockings and sex hormones as well as nanotechnology, genomics and many other areas of life as we know it. Philadelphia has a great new museum and admission’s free!

A view of the main gallery of the new Chemical Heritage Foundation museum.

The most spectacular display, a few feet in the door, is a large video projection designed by Theodore Gray. Conceptually the heir of the Eames’ multi-monitor display for the 1964 World’s Fair, it illustrates the periodic table, element by element and is as visually dazzling as it is didactically effective.

Kaleidoscope image of bakelite, one of the chemical contributions displayed in the new museum. Kaleidoscopic wallpapers and screen savers are available at the CHS website.

The museum is in an Italianate bank building renovated with great taste by Daget-Saylor Architects; they’ve created an 8,000 square foot open space for the museum that sparkles with glass and light. The permanent exhibition, occupying the bulk of the space, was designed by Ralph Applebaum Associates, the country’s premier museum designers. A smaller gallery at the back is for changing exhibitions.

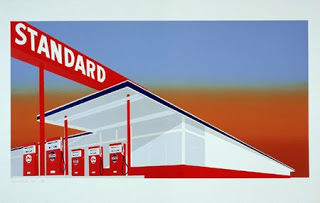

I went to the CHF because I’d run into Diane Burko who said that an exhibition had opened there, Molecules That Matter, organized by the Tang Museum at Skidmore College, her alma mater. It includes artwork in its exploration of ten significant molecules discovered or synthesized in the Twentieth century including aspirin, DNA, polyethylene and Prozac. Diane was surprised that I knew anything about chemistry; well I know a little.

Roxy Paine SCUlpture MAChine extruding her SCUMAK pieces.

The element that distinguishes all living things is carbon which bonds with other elements in three-dimensional structures, so that organic chemists need to conceptualize in three dimensions as do sculptors. I assumed that the artists might have done something related to chemical structure, but the use of the art was less conceptual and more illustrative. The section on aspirin, the first mass-marketed pill, includes Fred Tomaselli’s 13,000 (1996) created from columns of aspirin tablets on a black background encased in acrylic. To illustrate nylon Susie Brandt used old stockings to weave a large, plaid wall hanging that recall’s potholders made in crafts classes; she called it After Albers (1995-9) for Anni Albers, the Bauhaus textile designer. I enjoyed the discussion of nylon; apparently after World War II there were shopping riots when nylon hosiery first appeared, and 64 million pairs of stockings sold in four days.

The display on polyethylene includes four of Roxy Paine’s SCUMAK pieces, created with the use of a SCUlpture MAKing machine which extrudes polyethylene mixed with pigment; these were all black and looked like goth versions of Linda Benglis’ work. Behind the Paines a bench by Dan Peterman, made from recycled post-consumer plastic, fit so seamlessly into the display that I thought it was gallery furniture.

As part of the lecture series planned around Molecules that Matter, artist Chrissy Conant will be speaking about her Chrissy Caviar project on October 21 at 6pm. The galleries open an hour before the lecture.